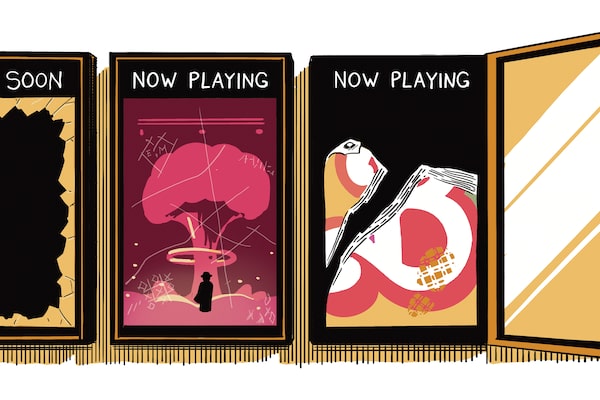

Illustration by Steven P Hughes

This Sunday evening, Hollywood will gather to celebrate itself under a mushroom cloud of pink glitter – and it won’t take too long to feel the radioactive fallout.

Thanks to the cultural phenomenon of Barbenheimer, this year’s Oscars stand to go down as the most box-office-friendly Academy Awards in a generation, perhaps stretching back to when Titanic triumphed in 1998. Sure, last year’s ceremony had blockbuster bona fides thanks to Avatar: The Way of Water and Top Gun: Maverick, but both felt included only as a courtesy, with no real chance of snagging the top-tier statuettes (sensing as much, both James Cameron and Tom Cruise skipped the ceremony).

This time around, though, there is every reason to expect that Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer will walk away with best picture and a boatload of other awards, while Greta Gerwig’s Barbie should snag at least one or two little gold men (I’m Just Ken for best original song is as close to a shoo-in as the film has). If you want your ailing awards show to prove its worth to today’s moviegoers, this is exactly how you do it.

Yet while the Oscars will shine a big, burning spotlight on the two biggest films of 2023 – films that proved the magic of moviegoing can never be replaced, ever! – it will be doing so as Hollywood faces several extinction-level events, from the streaming wars to strike fallout. Will Sunday go down as the night that saved Hollywood, or the last great gasp of an industry on fire?

The evidence for the latter is as inescapable as that dang dog from Anatomy of a Fall. While this Sunday’s ceremony arrives on the heels of a strong weekend at the North American box office – where Dune: Part Two scored US$81.5-million – the year so far, and the months ahead, feels especially apocalyptic.

Oscars guide 2024: How to watch the ceremony, nominated films and more

Up to this past weekend, the 2024 domestic box office has delivered just US$866.4-million in ticket sales, a drop of nearly 18 per cent from 2023 (a year that wasn’t exactly burning up the charts, either). Theatres in major U.S. markets are shuttering with increasing frequency – Detroit now just has one first-run cinema left in the entire city; New Haven, Conn., is down to zero after the Criterion Cinemas closed this past fall – and no one seems to be in a rush to build new ones. (Of the three major national U.S. theatre chains, only AMC has opened a new location in all of 2023.)

In Canada, it’s just as bad, as highlighted by a Telefilm study released last month that revealed 98 per cent of movies watched by Canadians in 2023 were consumed at home, not inside theatres.

Even the occasional success story lands as a dubious achievement. When the action-comedy Argylle took the No. 1 spot at the box office in early February, it became the lowest-grossing film to do so since 2021. And Dune: Part Two’s triumph? Denis Villeneuve’s sci-fi epic might have delivered the biggest opening of the year, but that’s only because there has been precious little competition. (Unless you count something like Madame Web as competition, which you definitely should not.)

How did it come to this? The wounds of the pandemic of course have yet to heal – in fact, they’re festering – but a good deal of Hollywood’s injuries are self-inflicted.

Studios rushed to embrace streaming, either unaware or unwilling to acknowledge that they were abandoning a business model that worked for generations. Where once, they’d give a movie an exclusive theatrical opening that preceded several downstream tiered windows of release, each feeding the other in terms of marketing awareness and revenue, they now double down on a new and sexy but unproven model that was filthy with cutthroat competitors.

Worse still: It was a business in which studios were incentivized to plunder the supply of their traditional partners (movie theatres) in order to bulk up their own nascent enterprises (streaming). And once audiences cottoned on to the idea that movies are going to be made available to watch at home just a few weeks after they open in theatres, who was going to rush to book the babysitter for an increasingly costly evening out?

But the streaming debacle feels almost understandable (look at all the pressure those poor movie executives were under from Wall Street!?) when compared with how the Hollywood strikes were handled. By refusing to even engage with the labour unrest for months – not to pick on Disney here, but what kind of leadership did CEO Bob Iger think he was practising when he said SAG-AFTRA was not being “realistic” the day after it was revealed his annual target bonus was raised from $1-million to $5-million? – the major studios created their own worst nightmare.

Turns out that not having movies in production for half a year reduces the number of movies you can actually release, and thus decimate your revenue. While 2023 delivered 124 wide theatrical releases (as in movies that opened on more than 1,000 screens in North America), 2024 will only see 107. This is why January and February felt especially sleepy – not a single wide release opened the weekend of Jan. 26, and it’ll be the same two weeks from now – and why the summer is going to look as wonky as Paul Giamatti’s wandering eye(s) in The Holdovers. (That’s a movie, by the way, that might’ve earned more than US$20.2-million at the box office had it not been made available to watch at home a mere 20 days after its wide theatrical release.)

Add into this deficit of releases the very real chance that 2024 might end with one (or two) fewer studios thanks to a frenzied climate of mergers and acquisitions. Paramount is a good candidate to become absorbed, while avaricious eyes see Warner Bros. Discovery falling into the hands of Universal Pictures’ owner Comcast, and there stands to be that fewer films. Oh, and don’t forget about yet another industry strike that’s looming, with the major crew union IATSE having authorized labour action as its two major studio contracts expire July 31.

Given how studios have taken to treating everyone from artists to crews to audiences like the nacho cheese stuck to their loafers, it might be easy to muster sympathy for, say, movie theatre owners, whose business shifts from weekend to weekend on the whims of the most unpredictable industry going. But exhibitors – at least the major players – haven’t been endearing themselves to their customers, either.

In Canada, moviegoers are practically spoiled for grievances, from Cineplex’s online ticketing surcharge (which has brought in almost $40-million for the company since launching in June, 2022) to having to pay extra to see those increasingly rare releases of wide interest. (Dune: Part Two did so well in small part because it cost $1 more to see at many Cineplex and Landmark locations than any other new release.) Expecting meticulous presentation and decent audience behaviour, too? Godspeed.

America Ferrera, Ariana Greenblatt and Margot Robbie in Barbie.Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures/Warner Bros.

Not all hope is lost. With the strikes now settled, the number of wide releases should creep back up to expectations by 2025. This summer looks to include at least a few hits that might actually be fun to watch (all eyes are on you, George “Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga” Miller). There has been enough buzz and activity at festivals and markets so far this year – from Sundance to Berlin – to get independent distributors excited. And if Nolan does indeed walk away with all his Oscars on Sunday night, it will serve as proof that there is still room for adventurous filmmakers to work inside the studio system on the largest scale possible.

But even the glitziest Barbenheimer blowout cannot distract from that ticking sound that Hollywood must hear in the distance. Like a certain physicist, the film industry has started a chain reaction that might destroy its entire world. Bombs away.