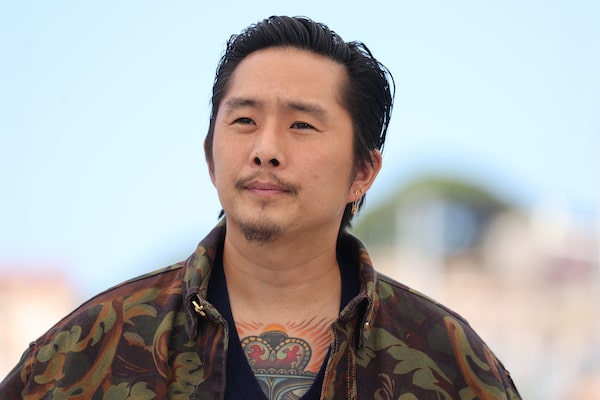

Justin Chon on the set of Blue Bayou.Ante Cheng / Matthew Chuang / Focus Features/Focus Features

Plan your screen time with the weekly What to Watch newsletter. Sign up today.

It’s strange to hear Justin Chon without a Southern drawl.

In Blue Bayou, which he wrote and directed, Chon disappears into the character of Antonio LeBlanc, a Korean adoptee who is turning his troubled life around in New Orleans. He loves his pregnant wife, Kathy (Alicia Vikander), and young stepdaughter Jessie (Sydney Kowalske), taking great pains to get away from his lucrative but shady past as a motorcycle thief. After a police run-in, his (lack of) citizenship status becomes a flashpoint that threatens to tear him from his family and the only life he’s ever known.

The film, which premiered at Cannes, is Chon’s fourth feature. For some, he rose to prominence as Eric Yorkie in the supernatural YA franchise Twilight. Others may know him better for winning the NEXT Audience Award at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival for his film Gook – which he also wrote, directed and starred in.

Chon’s latest film takes him the furthest he’s ever been outside his own skin with a little-known story – someone else’s story – of immigration. He got to know many adoptees whose experiences were the inspiration for Antonio and the challenges thrust upon him. For various reasons, these adoptees did not have their U.S. citizenship properly looked after, a circumstance that, if discovered, could lead to deportation.

Over Zoom from Los Angeles, Chon unpacked the complicated issues that ground the world of Blue Bayou.

Justin, you’ve gone now from Cannes to opening day. How does it feel to have this film finally out there after spending so many years on it? Four or five years was it?

It feels great. I’m anticipating the types of people who will see this and hoping that the right people will see this, so that the purpose of the film can be fulfilled.

Who are the right people in your mind?

Legislators, people who can actually do something about this issue. It’s pretty shocking how very few people know that adoptees are getting deported. It’s always been such a Mexican issue and a border issue, rather than immigration policy that also affects other people.

Blue Bayou, which premiered at Cannes, is Chon’s fourth feature.VALERY HACHE/AFP/Getty Images

I read that you had hundreds of hours of conversations with adoptees in making this film. How did that feedback inform the film?

One adoptee told me that a big moment in an adoptee’s life is when they have a child of their own, because it’s finally the first time in their life that they have someone that’s blood-related to them. When Antonio holds his child for the first time, he doesn’t say anything, but it’s very much emotionally felt. He’s like, “Oh my God, I’m holding my child.”

There’s also the misconception that an adoptee’s parents didn’t want them or wanted to kill them, when a lot of times it’s circumstantial. Those types of things crept into the film and I made sure to include them.

You’ve been asked a lot about intent, and who gets to tell whose stories. Now that you’re through the other side, what was the most important thing you did or learned as a storyteller?

Films can be powerful and actually change popular perception. So, normalizing things like interracial marriage. The fact that Antonio has a Louisianan accent and normalizing that we exist in those parts of the country. It shouldn’t be weird that an Asian man has a white stepchild. The fact that Vietnamese people do exist in the South and they were relocated there. That we can have multiple Asian-American ethnicities in one film and have them interact.

I think the best way for us to step into other people’s shoes and become empathetic is to tolerate this type of storytelling. It might not be your own experience, but give it two hours of your life and see what it does.

How do we best bridge those gaps of experience in our communities, between those who more or less grow up here versus those who immigrate at later ages?

Somebody told me you shouldn’t be able to tell someone else’s story until you’ve told your own effectively. So I started off telling Korean-American stories, but now it’s time that I be of service to other Asian ethnicities. I’ve just finished shooting a film with [Indonesian-born rapper] Rich Brian about an Indonesian father and son. I just directed the adaptation of [author Min Jin Lee’s] Pachinko for Apple TV and that’s in Korean, English and Japanese. I think it’s our responsibility as Asians to support one another. Go tell your own personal story, but also know that we need you in other spaces.

New Orleans feels almost like a dream at times the way you shot on film. You’ve mentioned John Cassavetes as an influence. Which of his films would you say are your favourite?

A Woman Under the Influence. Faces. The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. His films are very tactile, very personal and very human. I don’t even necessarily have to get into the story, it’s just about moments in his films.

At the same time, it’s funny: If you use a hand crank like I did in the film or any weird form of photography, people automatically go, “Oh he was influenced by Wong Kar-wai.” It’s not! Of course I love Wong Kar-wai, it’s a flattering thing. But it’s so funny because the hand crank was actually inspired by Tony Scott.

I was actually going to mention Wong Kar-wai before I read your production notes.

But it’s okay. That’s just our perception of Asian people in cinema, that that’s who we go to when we use those techniques. Wong Kar-wai was a genius and he changed the face of cinema forever. If they want to compare me to Wong Kar-wai, do it all day.

This interview has been edited and condensed. Blue Bayou is available in theatres starting Sept. 17.