Author: Soraya Chemaly

Title: Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger

Publisher: Simon & Schuster, 392 pages, $36

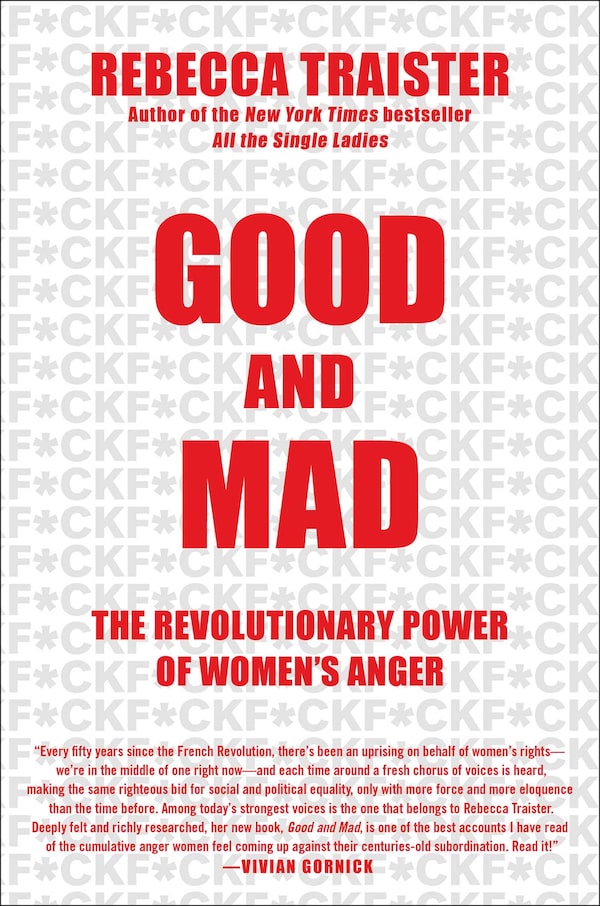

Author: Rebecca Traister

Title: Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger

Publisher: Simon & Schuster, 284 pages, $36

In the fall of 1981, a group of British women chained themselves to the fence surrounding the Greenham Common military base to protest the presence of American nuclear weapons deployed there. Female peace activists lived there, sometimes in the thousands and sometimes just a few, for almost two decades.

They had a songbook, of course. Singing would have provided a useful distraction from being chased by bulldozers and mocked by passersby. One of the songs was called Brazen Hussies: “We’re brazen hussies, and we don’t give a damn/We’re loud, we’re raucous/and we’re fighting for our rights.”

They were officially known as the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, and less officially, in certain bilious quarters of the media, as witches, harpies and “smelly lesbians.” Four years before they set up camp, across the world, another group of women had taken their fury and grief and turned it into political action: In Buenos Aires’ Plaza de Mayo, dozens of mothers whose children had disappeared during Argentina’s military dictatorship began protesting and demanding justice. They were called las locas, “the madwomen.”

Women’s anger has always been a momentous thing, fuelling social-justice movements and individual action. As two new books demonstrate, that rage has also been denigrated (“the madwomen”), ignored, painted as hysterical and unfeminine, used to divide women from each other and been dismissed as unserious and transitory. It has been fatally underestimated by men who find it puzzling, threatening and terrifying. Which is how we find ourselves here, in this particular historical pickle, with half the population grinding its molars to nubs and the other half turning to each other with panicky eyes, whispering: What the hell’s going on?

American journalist Rebecca Traister begins Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger with a scene from the 1972 Democratic National Convention, where feminist activists furiously protested the lack of media coverage for Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman elected to Congress, who was vying to be the party’s presidential nominee. The white, male journalists at the convention were nonplussed, and one tried to placate the lawyer and activist Florynce Kennedy. “Don’t touch me,” Kennedy bellowed at him, adding a choice expletive that cannot be repeated here, sadly.

Watching the footage more than four decades later, Traister writes that she found the activists’ rage thrilling and liberating, but also wondered if such demonstrations in 2015 would feel “anachronistic, theatric and unnecessary.” Hadn’t we come so far, baby? Two and a half years later, at the Women’s March on Washington – a seismic eruption of activism spurred by Donald Trump’s election – she would witness that fury again, and it wouldn’t seem anachronistic at all. The bear had just been hibernating, lulled to sleep with a false sense of safety.

In other words, we hadn’t come so far after all. And this is the main thematic point joining these two fine books, although “point” is an imprecise word because what joins them is in fact a gap or a chasm: The gap between how much progress we thought we’d made in the world and how unjust it still remains; and the gap between women’s fury and men’s ignorance of it. “If men knew how truly angry the women around them often are – and understood the structures enforcing women’s silence – they would be staggered,” writes Soraya Chemaly in Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger.

handout

It is Chemaly’s business to outline these structures of silence, a blueprint for the red mist. Chapter by chapter and study by study, she builds a case for why so many women feel a deep sense of injustice. They are socialized as girls to suppress their anger because it’s so unfeminine and off-putting, and later sold cosmetic surgery procedures to correct their “resting bitch face.” From boardrooms to legislatures to kitchens, Chemaly compellingly maps the sources of this grievance. As a final indignity, women’s anger is attributed to hormonal imbalance rather than a perfectly reasonable reaction to a world in which power and control – even over their own bodies – are still beyond their reach.

“Is it possible to read a book about anger and not get mad?” asks Chemaly, who is the director of the Women’s Media Center Speech Project. “I haven’t found it possible in writing one.” What she’s getting at here – which Traister also emphasizes – is the double-bind nature of women’s fury. In suppressing it, women are driven mad with frustration; express it, and they’re penalized. Chemaly quotes the writer and activist Andrea Grimes: “I am a woman who is very angry and very tired. I know that that makes me unlikeable. I know this will literally cost me money in lost bylines and recognition and respect from men who decide who gets hired to write what and when.”

Traister’s book takes a narrower focus – she concentrates on the history of women’s political anger in America, leading to the #MeToo reckoning – but her writing is so incendiary, and her analysis so smart and compassionate, that the margins of my copy of Good and Mad were scribbled full of exclamation marks and “omg yes!” Almost as if a madwoman owned it.

Here she is on the unreported consequence of #MeToo, which she astutely understands as a hole in the public imagination, a place deprived of the women who could have enriched it: “We just don’t consider, don’t even see, the loss of all the women who – driven out, banished, self-exiled, or marginalized – might have been more talented or brilliant or comforting to us, on our airwaves or in our governing bodies, but whom we have never even gotten the chance to know.”

And it’s women of colour who are disproportionately harmed by the demonization of their legitimate anger, as both Chemaly and Traister explain. Black women in the United States never had the privilege of thinking everything was okay, and now have to bear the double burden of teaching their freshly enraged white peers about useful dissent (and we’re not even talking about the 53 per cent of white women who voted for Donald Trump). Traister quotes Stacey Abrams, the Georgia Democrat who will be the first black female governor in the country’s history if she’s elected in November: “They’ve seen, for the first time, the real consequences of inaction. So you have women who are waking up and seeing that they don’t have the luxury of going back to sleep.”

What, finally, is to be done with all this anger? The anger that propelled the women of Greenham Common and the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and the supporters of Shirley Chisholm, but brought them nowhere close to justice? (Forty-six years after Chisholm’s historic run, Americans have yet to see a woman occupy the White House – not even a measly vice-president.)

The gap between what is and what should be is depressing to contemplate. However, little gets accomplished in the pit of despair. Both authors agree that hopes lies in fury harnessed to action, as it has been with a recent wave of political activism and a renewed fight against sexual misconduct. Rebecca Traister finds the message delivered powerfully in the words of Zora Neale Hurston: “’Grab the broom of anger and drive off the beast of fear.” That may be the only broom that women will happily take out of the closet, and keep nearby.