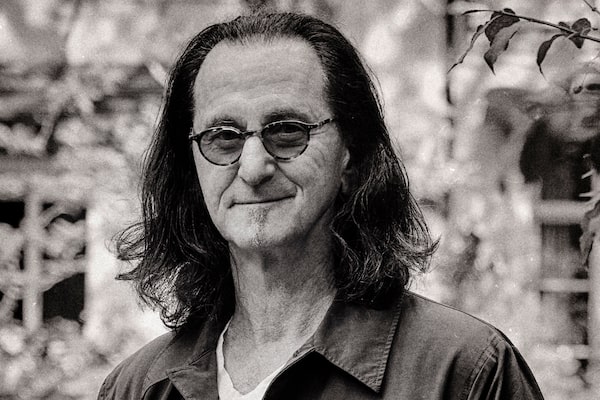

Geddy Lee.Richard Sibbald/Supplied

- Title: My Effin’ Life

- Author: Geddy Lee

- Genre: memoir

- Publisher: Harper

- Pages: 512

In the first sentence of his memoir, My Effin’ Life, Rush bassist Geddy Lee states that the name given to him at birth was Gershon Eliezer Weinrib, after his maternal grandfather who was murdered in the Holocaust. Why “Geddy Lee” as a stage name? It’s complicated, but, as he explains, in his desperation to assimilate into a less ethnic world, he didn’t think Weinrib sounded rock ‘n’ roll enough.

The memoir from the 69-year-old musician is an exercise – he’s working out some things. We know, going in, that he is the high-voiced singer of the now-retired Canadian progressive-rock trio enshrined in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. But that’s just the tip of the pyramid.

Books we're reading and loving this week: Globe staffers share their book picks

As much as a chronicle of his rocking past, his book is a thoughtful documentation of identity and a lucid account of how it evolved.

A chapter is devoted to his parents’ incarceration in camps including Auschwitz during the Holocaust. His mother, Mary Weinrib (née Rubinstein), was born in Warsaw. The Nazis had a name for her: Slave #A14254. He suggests readers simply looking for juicy rock ‘n’ roll bits in his book might wish to skip the chapter – “I won’t blame you.”

Lee won’t blame you, but I will.

After the Second World War, his parents got married in what had been an officers’ mess hall in a former concentration camp in Germany. Immigrating to Canada, they raised a family in the suburbs of Toronto. His father, Morris Weinrib, died at the age of 45. His heart, Lee believes, had been damaged by six years of slave labour during the war. “I believe he’d suffered not just physically but spiritually too – by which I mean he lost his religiosity.”

Lee was 12 years old. Because his mother’s side of the family in Poland were Orthodox Jews, there was a strict set of rules for grieving. “These stages of mourning affected me profoundly,” he writes, “and, I believe, set the stage for my life to come.”

My Effin’ Life is often about death and more than once deals with insurmountable sorrow. “My mother’s grief knew no bounds,” Lee writes about the effect of his father’s death. “She was devastated, and although life did carry on, she never fully recovered in her heart.”

In 1997, Selena Taylor, the only child of Rush drummer Neil Peart, died in a single-car crash. Peart’s common-law wife of 23 years, Jacqueline Taylor, was diagnosed with terminal cancer not long after. “Neil kept telling me, as he told everyone else close to him, that she was willing herself to death, unable to live in a world without her beloved daughter,” Lee recalls.

By the time Peart himself died of brain cancer on Jan. 7, 2020, at the age of 67, Rush had already disbanded.

“So many endings, too many people departed,” Lee writes in the final chapter.

Not that the memoir is morbid. When it comes to sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, My Effin’ Life checks off two of those boxes. There are colourful road stories from the group’s local bar-band days – five sets a night at Toronto’s Gasworks club – and the years headlining arenas internationally. Once, in the days before GPS, they found themselves driving from St. Louis to Cleveland via Memphis. AC/DC famously sang that it is a “long way to the top if you wanna rock and roll.” Even longer when taking the wrong road.

Each of the Rush albums is explored in detail (perhaps too much so for non-fanatics).

Drugs? You bet. The making of 1975′s Caress of Steel, for example, was fuelled by hash oil. And the band eagerly embraced the cocaine practices of the era, according to Lee. “We all started out as occasional users, but from ‘77 into the early eighties it increasingly became a common part of our impedimenta.”

There is no sex in Lee’s life story, though we know the father of two experienced it at least twice. If the Fly by Night band had groupies, Lee isn’t saying.

My Effin’ Life was written with help from a friend of his, Daniel Richler, the broadcaster and writer thanked in the book’s acknowledgments as an editor, grammar instructor and literary mentor. (Whose choice was it to lean into the semi-expletive in the title? It is sprinkled though the 512 pages dozens of times, sometimes within the useful footnotes.)

Like Rush guitarist Alex Lifeson, Lee grew up in the Toronto suburb of Willowdale. The location is mentioned in the autobiographical song The Necromancer: “As grey traces of dawn tinge the eastern sky, the three travellers, men of Willow Dale, emerge from the forest shadow.”

As a kid, Lee was a nerdy, big-nosed loner who was “chronically indecisive, a procrastinator, vague and aimless, possessed of few opinions.” As a teenager, music took over. Though it devastated his mother, he quit school for a rock ‘n’ roll career and stuck to it: “I had no other skills.”

A young Lee and his friends were “weekend hippies” and “wannabe freaks” who took the bus south to Toronto’s Yorkville Village to walk among the bohemians. Years later, Rush played the giant SARSStock benefit concert with the Rolling Stones in a suburban park near where Lee was raised. That day, the cool people came north to see Lee and Rush.

In school, he endured antisemitism. He wished for the “power to become invisible,” so that he could walk the halls without being afraid. But as an adult he took to wearing a mezuzah around his neck. Opening for Kiss in Texas, that band’s Jewish bassist Gene Simmons took hold of the pendant and told Lee, “You shouldn’t wear that down here. It’s dangerous to advertise you are a Jew.”

The Lee who emerges in My Effin’ Life is a strong-willed, deceptively cocky and artistically uncompromising artist in trio of brilliant outsiders who defiantly and proudly operated on their own terms.

At a recent book-launch event at Toronto’s Massey Hall (where Rush recorded the live album All the World’s a Stage in 1976), Lee told a sold-out audience that he wouldn’t change a thing in his life. Reading his book, I effin’ believe him.