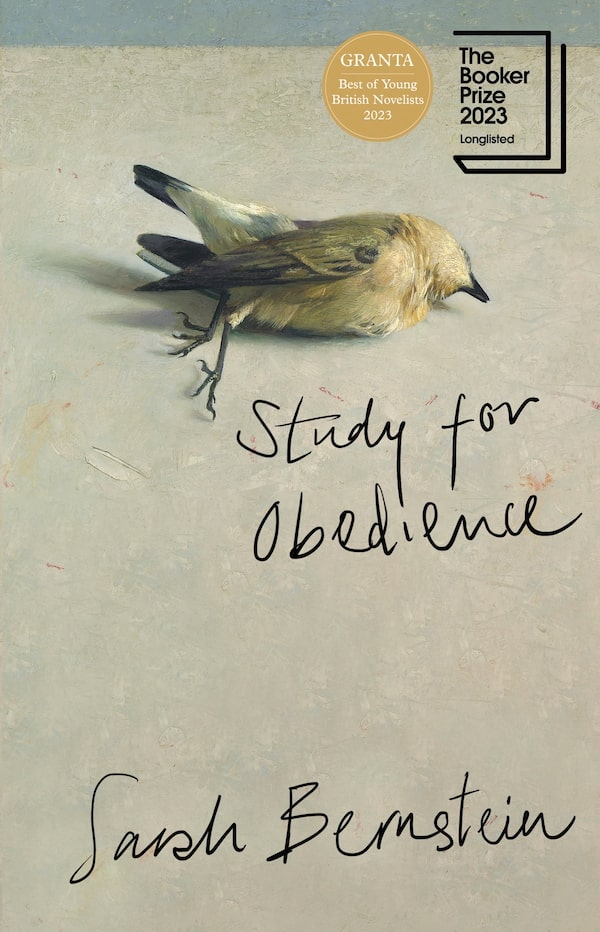

Study for Obedience, by Sarah Bernstein.Handout

- Title: Study for Obedience

- Author: Sarah Bernstein

- Genre: Fiction

- Publisher: Knopf

- Pages: 208

“It was the year the sow eradicated her piglets. It was a swift and menacing time. One of the local dogs was having a phantom pregnancy. Things were leaving one place and showing up in another.” The opening lines of Study for Obedience sound a little like what AI might produce if you asked it to rewrite those of A Tale of Two Cities, but with a much stronger sense of foreboding. And animals.

Which is not meant to disparage Sarah Bernstein’s strange, unsettling and profoundly beguiling book. Bernstein, a poet from Montreal now living in the Scottish Highlands, is hailed on the cover as “an extraordinary new voice in Canadian fiction.” It’s the kind of epithet that publishers toss around all the time, so it’s nice, for once, to be able to wholeheartedly agree. (As apparently did this year’s Booker judges, who long-listed her for that prize.)

Books we're reading and loving this week: Globe staffers share their book picks

Our narrator-protagonist is a young woman who has come to a small town in an unnamed northern country to act as housekeeper for her elder brother, a wealthy, recently divorced businessman. Their family – who selective details suggest are Jewish – have ancestral connections to the town, but were also persecuted and driven out. Indeed, the brother’s home, a sprawling manor on a hill above the town, once belonged to “the distinguished leaders of the historic crusade against our forebears.”

Outside of the fact that she did an unsuccessful stint as a journalist and is now an audio typist for a legal firm, the narrator gives scant details about herself. Her description of her childhood, though, stops us in our tracks: “I was the youngest child, the youngest of many – more than I care to remember.”

Author Sarah Bernstein.Alice Meikle/THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO

Tending to these mysteriously uncountable siblings, we’re told, in her characteristically formal, gnomic manner of speaking, that her role had been to smooth away any “discomfort” by serving “their meals and snacks, their cigarettes and aperitifs, their nightcaps and bedside glasses of milk.” Cigarettes and milk? (The narrator, too, is a devoted smoker.) Aperitifs and nightcaps? Who are this eccentric brood? And what year is it, anyway?

Thirty-three books to read this summer

At her brother’s house, the narrator’s “housekeeping” duties include bathing and dressing him. And though she claims to enjoy doing so, we also learn to take these kind of pronouncements – including that she is “inept” and “blundering”– with a grain of salt, given her tendency toward self-abnegation, and her brother’s toward dominance.

When the brother leaves on a business trip, the narrator, suddenly at loose ends, distracts herself with a visit to the village. There, the townspeople visibly recoil from her, parents covering their children’s eyes as she passes them by. She can only guess at the reasons for such behaviour. Despite being a master of several languages, the town’s local dialect – to her shame – eludes her.

Her brother, on the other hand, can speak it fluently, so he arranges with the townspeople – who seemingly have no issue with him – for his sister to help out on a local farm, the condition being that she simply do her work and never try to communicate with anyone.

2023 in books: 30 highly anticipated Canadian titles coming this year

The undertaking of her new duties, however, coincides with a series of disturbing, animal-related mishaps in and around the community. A ewe dies while caught in a fence with her half-born lamb sticking out of her. An entire herd of cows goes mad, requiring that they be culled. A wave of avian flu sweeps through the chickens. The locals’ hostility turns to fear. They’re certainly not reassured by the narrator’s unexplained habit of weaving human figures out of reeds and leaving them on their doorsteps.

The absence of dialogue – everything is filtered, monologue-style, through the narrator – adds to a building feeling of claustrophobia and uncertainty. Can she really be the cause of all the chaos and dyings-off? Correlation isn’t causation, of course, but try telling that to the townspeople. Now when the narrator enters the local diner to grab a bite, the place practically clears out.

As the sinister events multiply, Bernstein keeps us in limbo between the specific and the undefined. And our initial sense that this is some kind of fairy tale or fable is periodically upended by incursions of modern digital life, references to Twitter and Microsoft Teams landing like frying pans to the head.

When the brother finally returns, the narrator outwardly returns to her servile role. She washes him and feeds him and reads Montaigne to him. But something has shifted, subtly at first, in their power dynamic in a way that is best read to discover.

The sly ambiguity of Study for Obedience practically demands rereadings. And while the story of the stranger who arrives in town and appears to upset the order of things is an old one, Bernstein’s novel feels entirely original; something ancient and unnervingly modern all at once.