Supplied

- Title: Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas

- Author: Glenn Kenny

- Genre: Non-fiction

- Publisher: Hanover Square Press

- Pages: 400

- Title: Paul Thomas Anderson: Masterworks

- Author: Adam Nayman

- Genre: Non-fiction

- Publisher: Abrams

- Pages: 288

It would not be fair to say that the state of contemporary film criticism has reached a crisis point. But things are not exactly footloose and fancy-free. Media organizations mainstream and alternative are disappearing, conglomerating or treating arts coverage as a nice-to-have luxury. And those of us who are currently defying the odds are now faced with a beat that is itself undergoing an existential reckoning. We’re no longer big, and the pictures got small.

There are, though, shouts of hope on the periphery. Even if they arrive from voices who do not have a full-time home (whether that’s by choice or not is neither my business nor yours). New from Glenn Kenny, a long-time critic and journalist whose writing now appears in The New York Times and RogerEbert.com, comes Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas. And from Adam Nayman, a Toronto-based contributor to The Ringer, Sight and Sound and other publications, comes Paul Thomas Anderson: Masterworks. The two books take highly divergent approaches to film writing – what it can or could achieve – but both remind readers and moviegoers that there is life out there beyond a Rotten Tomatoes score.

Supplied

Kenny’s Made Men is the more commercial prospect of the two books, not only because it deals with a filmmaker perhaps more active in the popular imagination and is told with a ticking-clock urgency, but because it’s got one hell of a hook: The fall of 2020 marks the 30th anniversary of Goodfellas, the finest and most rewarding film of the 90s. That’s an anniversary that has already brought out the best and worst aspects of contemporary film-writing culture; try to find a movie website without a hastily composed essay commemorating the crime epic’s influence. But Kenny’s work towers above the internet’s quick-hit listicle kings. This is film writing with enthusiasm and purpose.

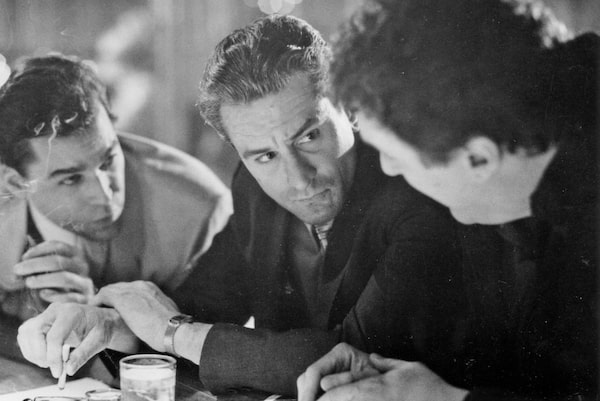

Across 400 intensely reported pages, Kenny traces the genesis, production, themes and legacy of Goodfellas with the exactitude of a scholar and excitement of a true Martin Scorsese acolyte. No detail is too small to discuss with fervent dedication and no participant given unfairly short thrift. Kenny talks to anyone and everyone involved in making the film, with the discussions expertly contextualized by a film writer who was in the thick of the scene at the time it was unfolding. As Kenny attempts to suss out the truths about Goodfellas’ producing-credit battle and just how large a contribution the real gangster Henry Hill played in the biopic about his life, the writer illuminates just how much sheer work and talent and pure dumb luck and goes into making a movie, let alone a good or great one.

Glenn Kenny, author of Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas.Supplied

Kenny’s dogged pursuit of every Goodfellas breadcrumb culminates with a bouncy, infectiously entertaining conversation with Scorsese himself, which is transcribed seemingly verbatim toward the end of Made Men. Even though by this point in Kenny’s writing – when it seems that we could know everything there is possible to know about Goodfellas – the author’s one-on-one with the master himself proves that there is just so much unknowable mystery to the art of filmmaking that maybe knowing we can never know everything is, well, knowledge enough.

Nayman’s Paul Thomas Anderson: Masterworks doesn’t include any exclusive one-on-one conversations with the subject in question, but that proves itself to be a feature rather than a bug.

Although the back pages of Nayman’s book include a handful of interviews with regular Anderson collaborators that are entertaining (cinematographer Robert Elswit), insightful (editor Dylan Tichenor), and curiously short and perfunctory (composer Jonny Greenwood), Masterworks is not intended to be a deep journalistic endeavour interrogating those responsible for how and why movies get made. It has a touch of that, to be sure, but Nayman is more a passionate and erudite untangler of art than a meticulous explainer of just how things get made.

Ray Liotta, left, as Henry Hill, and Robert De Niro, centre, in Goodfellas.Warner Bros.

Each of Anderson’s eight films gets an imaginative and often beautiful essay, but despite the presence of the word “Masterworks” in the title, Nayman is not a blind admirer. The author convincingly argues the deficits of early Anderson films such as Magnolia – not without much admiration – while making the case that the director matured artistically at the same time that his movies’ settings journeyed further into the past.

Which explains why the book is not a chronological IMDb-esque run-down of Anderson’s work as he made it, but – with the one exception of the skeleton-key-like Phantom Thread – a contextualization of the man’s films according to when in history each story is set. By starting, then, with the early 1900s of There Will Be Blood and finishing (sorta) with the contemporary surreal rom-com of Punch-Drunk Love, Nayman offers not only a new window into understanding Anderson’s career, but a new model for any cinephile attempting to untangle the knotty medium.

Neither Made Men nor Masterworks is perfect. Kenny’s chapters can be repetitive and his sentences overexplanatory, sometimes pitching his writing to a reader who has never before watched a movie. And Nayman drifts into some bone-dry academic prose. Personally, I’m not sure I’ll ever get over his seeming glee of deflating the manic energy and perverted joy of Boogie Nights. But both authors are film-writing professionals. They can take a little criticism.

Mark Wahlberg and Julianna Moore in Boogie Nights.New Line Cinema via ONLINE USA

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.