Author Robert Young is a former golf pro and long-time friend of his book's subject, Moe Norman.Ash Nayler Photography/Handout

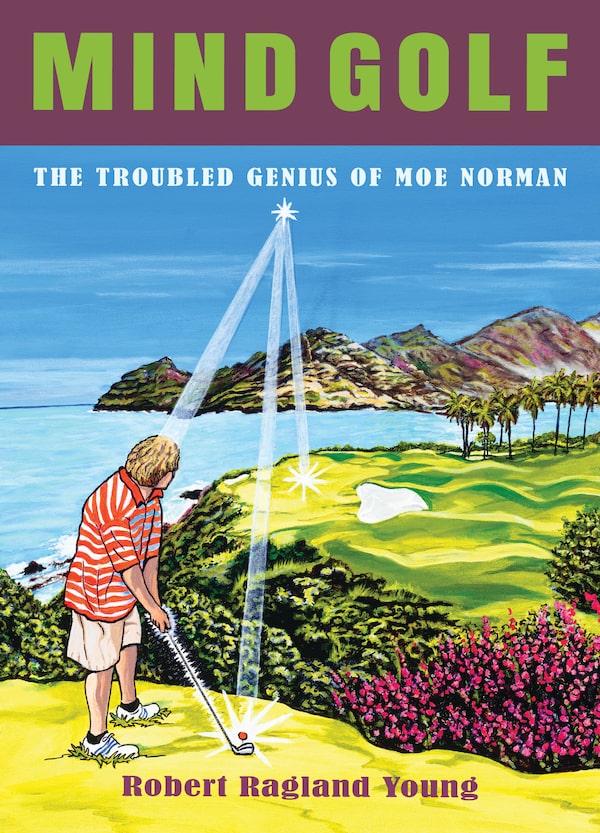

- Title: Mind Golf: The Troubled Genius of Moe Norman

- Author: Robert Ragland Young

- Genre: Sports

- Publisher: Savio Republic

- Pages: 208

Once, as a golf clinic’s star attraction, Moe Norman was asked what it was like to hit perfect shots so consistently. “You will never know,” was his smiling reply.

Norman was joking, but not really: He was as great a ball striker who ever lived. Most golfers truly will never experience his routine excellence. More could, though, if only they would think like Moe. Or so Robert Young believes.

Young is a former golf pro and a long-time friend of Norman, the Canadian legend who both dazzled and confused the golf-cleat class for decades before he died in 2004 at the age of 75. With Mind Golf: The Troubled Genius of Moe Norman, Young attempts to explain a socially awkward man whose arrow-straight shots resulted in 17 holes-in-one and earned him the nickname Pipeline Moe.

The book is not biography. It is an eccentrically written self-help manual and an attempt to convey the secrets of Norman’s peculiar mind. The author, who studied Norman up close for years, is passing on what he learned. One might call his efforts Zen, Tee Shots and the Metaphysics of Moe. The publisher calls it “the most unusual golf book ever written.” Tomatoes, tomahtos.

Handout

Mind Golf comes with a forward written by Neil Young, the rock star and author’s younger brother. “Moe Norman was a master of the game, and Bob spent more time with him than anyone for years and years,” he writes. And Neil would know: It was his financial support that enabled his brother’s life on the fairways.

There are multiple books on Norman, including Moe and Me, by former Globe and Mail writer Lorne Rubenstein. Stories about Norman’s oddball behaviour are part of Canadian sporting lore, to which Young adds first-hand experiences.

In the early 1980s, he came upon Norman poking a golf shaft into the sand around the parking lot of a Florida course. “What are you doing?” Young asked.

“Looking for something,” Norman responded.

“How much have you got buried here, Moe?”

“Eight, ten thousand. Yup. I’ll find it.”

The golfer had buried thousands of dollars in a fruit juice can. (And, yes, he found it.)

Norman did not believe in banks. He lived in motels, drove a Cadillac, disregarded personal hygiene and drank Coca-Cola by the crate. The non-conformity was a handicap; the stuffy folks who ran the Royal Canadian Golf Association (and the PGA Tour) did not accommodate him. “He did not have the social grace they expected,” Young writes.

Colson Whitehead delves into history of his home in Crook Manifesto

The unusually focused man did not have a wife or girlfriends. His passions were golf, all-you-can-eat buffets and more golf. It was a life of exclusion and a monk’s inwardness, with no clutter to disrupt the mental platform from which he created the shots he first visualized and then executed.

As Young writes: “He saw the world of business, the conflicts, the wars, the turmoil of human relationships, and he said, ‘No, not for me,’ and went to the golf course and the game of golf, and he stayed there.”

Mind Golf is Young’s first book. He writes in an intense, direct style, with a well-meaning passion that can be problematic. After several chapters, he is still explaining what he is writing and why he is writing it – selling something the reader already has in their hands. This is why books have introductions.

And this is why writers, particularly novice ones, have editors. Did Young have one? Norman is compared to the great American golfer Ben Hogan no less than five times, the repetition near word for word.

We could do without the long story about the author’s involvement in a landmark soft-drug case in the 1980s. It is worth a mention, sure. But a distracting nine-page rant against the Canadian judicial system? Objection, Your Honour, irrelevant!

That said, it is Young’s idiosyncratic narration that accounts for the book’s charm. Some might read it and want to know more about the author’s own life. (Count me in that crowd.)

The nine-iron people will soak up the book’s instructions on how to “centerize” the body, quiet the mind and form the image of the shot-to-be.

Other “Moisms,” as the author calls them, are less generic. Norman is quoted as saying he was “very happy being alone.” Shortly before his death, however, he changed his story: “All my life, wrong.”

There are lessons, and then there are lessons.

Perry Chafe’s debut novel blends storytelling skill with family history and fairy lore

Brad Wheeler

Brad Wheeler