Supplied

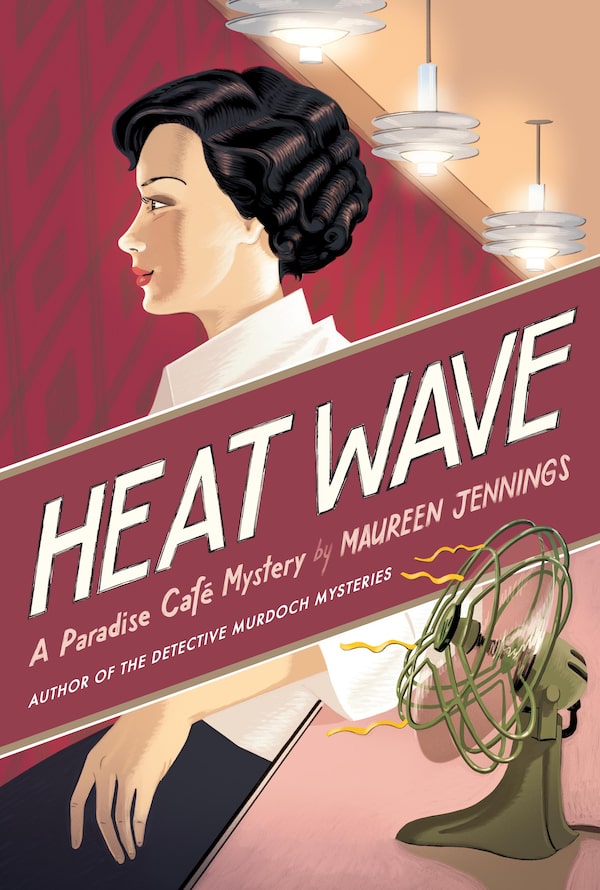

- Title: Heat Wave

- Author: Maureen Jennings

- Genre: Mystery

- Publisher: Cormorant Books

- Pages: 240

In contemporary fiction, the millennial-aged single woman is often a character through whom we identify our own paucity and miscalculations: the lack of children, money, stability or foresight providing a plot in which to flail. What a relief it is then to spend time with a protagonist who isn’t defined by the traditions she rejects – in the summer of 1936, no less.

Heat Wave, the first in Maureen Jennings’ new Paradise Café Mystery series, follows the myriad gumshoe conundrums of private investigator Charlotte Frayne, whose sleuthing skills are solicited for cases involving theft, murder and a string of disturbing incidents that turn out to be hate crimes as Nazi ideology seeps into Toronto’s underbelly. (Frayne works alongside Detective Jack Murdoch, the son of protagonist William H. Murdoch from Jennings’s Murdoch Mysteries series.)

Occupying the rare position of a female private investigator in the mid-1930s, Frayne works her way through undercover explorations that subject her to danger and constant sexism. Her life’s work is to find the lie. Although she lives in a permanent state of vigilance that many, even today, would consider paranoid, her instincts are never off. In this reliance on intuition, readers whose own watchful proclivities resemble Frayne’s may find familiarity. Frayne trots around from witness to witness, crime to crime, suspicion to suspicion, powered by hunches until she cracks the case. It is both exhausting to behold and successful as a commentary on the role of amateur community patrolling, backchannels and gut feelings that many women rely on in the absence of adequate legal structures. (Frayne somehow also finds the time to care for her elderly grandfather and to save a dehydrated horse.)

The dialogue, written to provide a sense of historical atmosphere, lands somewhat heavy-handedly. This is a book that wants to be optioned – the terse interactions between characters may as well be a wink at acquisitions departments. Given Jennings’s gentle undercurrent of morality, however, that could be a very good thing. Frayne takes an undercover waitressing job in a café run by four veterans who lived together as prisoners of war. Alcoholism, poverty and post-traumatic stress disorder are conveyed graphically and with compassion.

“I wasn’t sure how to respond, so I just made a sympathetic murmuring noise,” Frayne says when Murdoch regales her about the rats he’d seen during the First World War. “It had been almost eighteen years since the war had ended, and I constantly encountered evidence of its continuing aftermath. And now all the signs seemed to indicate we might be heading for another war. It was unbearable to think about.”

The subject of intimate partner violence is also discussed with clinical accuracy when the wife of an abusive husband is unable to verbally articulate the details of an attack. Frayne’s professional presence in these cases offers a unique stroke of empathy, her tactfulness an anomaly among the men she both investigates and collaborates with. Whether or not Jennings intended the book to be a statement on gendered labour division and emotional labour, it’s hard not to see it that way, especially in the context of the characters’ involvement in Communist politics. Frayne’s warm and caring instincts are put to use in her chosen career, a welcome reframing, given the era’s expectation that maternal skill sets be applied to domestic roles. If the police had their way, a wrongfully accused suspect would have been locked up for murder a few chapters in. But Frayne sees things polymathically, frequently noting the systemic problems that become everyday injustices.

Although Frayne is a workaholic, and surely an early prototype of today’s “millennial burnout generation,” toiling around the clock in record heat during the Great Depression, it is through her emotional intelligence – an aptitude that continues to be underestimated today – that the book’s key wisdom emerges. To paraphrase what our noble ace must recurrently remind herself: “Things are not always what they seem. … Never jump to conclusions until you have conducted a thorough investigation. … And even then, you might not be right. People can be astonishingly duplicitous.”

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.