Supplied

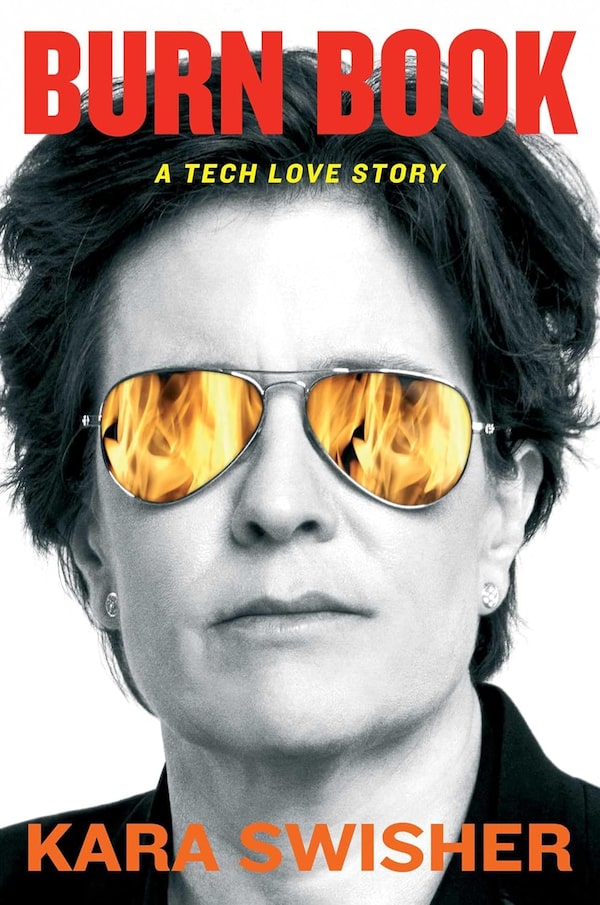

- Title: Burn Book: A Tech Love Story

- Author: Kara Swisher

- Genre: Non-fiction

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster

- Pages: 307

Kara Swisher occupies a unique place in business storytelling, bridging two worlds that rarely intersect. Having been one of the first mainstream journalists to take the digital revolution seriously in the nineties, she has for decades been a text message away from the most powerful people in tech, giving her access that in another reporter’s hands might prevent hard questions about how all that power is wielded. Yet much of the time, she actually asks those questions. Swisher is both at odds with and uncommonly close with tech’s ruling class.

And now she wants to burn it all down. After two reported books earlier in her career, Swisher’s latest, Burn Book: A Tech Love Story, comes in the form of memoir-turned-manifesto. She’s tired. The titans of technology on the American west coast no longer fascinate her; they grind at her. “An increasing number of these once fresh-faced wunderkinds I had mostly rooted for now made me feel like a parent whose progeny had turned into, well,” a word that can’t be printed in this newspaper, she writes.

When I started in daily journalism a decade and a half ago, bestowed with an iPhone 3G to make up for a salary that was barely above minimum wage, I wondered why, unlike most political reporters, many tech journalists didn’t seem to care about how power worked. They mostly seemed to fawn over, well, how Apple would improve upon the iPhone 3G – and, in the following years, how much the valuations of unprofitable startups could be juiced up. Swisher was a rarity until the late 2010s, when all those billion-dollar startups started to draw skepticism about their business models and how they use everyday people’s data. (Not without coincidence, this is when I became interested in covering tech.) Much of the finally skeptical reporting corps went on to write books about how, hey, maybe we’ve given too many of these companies unchecked power over society.

Now Swisher is adding her name to that mix. Burn Book is a welcome addition, with some caveats. As a statement, it feels like the natural culmination of the tech-will-save-us era – particularly given that Silicon Valley executives are now just as often covered by political journalists of D.C. as they make semi-annual shuffles into Congress to explain (but rarely meaningfully reckon with) their corporate decisions. Skepticism is mainstream. Sure, longtime skeptics, particularly on the left, have already written plenty of books. With Swisher’s latest in the canon, maybe a broader audience can see what they’ve been saying all along.

Which is this: Buoyed by some of the greatest market capitalizations in human history, tech companies have come to inherit power on par with governments – and without the checks and balances that make them adhere to the tenets of democracy. “For tech to fulfill its promise, founders and executives who ran their creations needed to put more safety tools in place,” Swisher writes. “They needed to anticipate consequences more. Or at all. They needed to acknowledge that online rage might extend into the real world in increasingly scary ways.”

The book also traces Swisher’s career from brash newspaper cub reporter to multiplatform entrepreneur-slash-pontificator, chronicling the evolution of the executives she’s encountered along the way. It’s not hard to figure out whom she’s most disappointed in (it rhymes with Dusk). But it’s fascinating to see how her views, augmented by her access, have shifted over time. Take Netscape co-founder Marc Andreessen, now one of the world’s most influential tech financiers, whose texts Swisher keeps on file like an emergency axe tucked behind glass in case of a fire. He “loved the media until he hated it,” she writes, becoming a “tiresome and aggrieved jerk, who has joined the grievance industrial complex.”

Then there’s Facebook magnate Mark Zuckerberg, who, “in contrast to the shark babies who tried to feign cuddly … openly craved power and historical significance from the get-go.” Despite watching him sweat profusely with anxiety during an on-stage interview early in his world-conquering career, she still convinced him to join her on her podcast years later, in which he justified not taking down Facebook content from Holocaust deniers. (He quickly backtracked.)

Swisher brings a less curious lens to her own relationships with tech giants, though she freely acknowledges her closeness with them in Burn Book. Access journalism can breed strange, conflicting intimacy. She admits to giving advice to numerous sources, some quite powerful, which, uh, most reporters in the mainstream press would probably get fired over. And she acknowledges that her then-wife was a prominent Google executive as it became one of history’s fastest-growing companies in the 2000s – which forced her to suspend her newspaper column as she worked toward launching a digital-media brand that would let her disclose such matters.

Still: her readers probably would have wanted to know these details at the time. They also probably would have wanted to know that, during the massive North American blackout of 2003, she and her then-wife invited Google executives Larry Page and Susan Wojcicki to stay at her mother’s New York apartment when they couldn’t get into their hotel rooms.

Again, Swisher occupies a unique place in journalism. She was very close to the powers she covered. And she clearly has regrets. The book is still a fascinating read for anyone who wants to know how tech magnates’ power works today.

Josh O’Kane is the author of Sideways: The City Google Couldn’t Buy and a Globe and Mail reporter who recently spent five years covering the ways technology is changing society.