Albert Woodfox pumps his fist as he arrives on stage during his first public appearance at the Ashe Cultural Arts Center with Parnell Herbert, right, in New Orleans, La., on Feb. 19, 2016 after his released from Louisiana State Penitentiary earlier in the day. Solitary is evidence of Woodfox’s extraordinary mental resilience in the face of relentless state cruelty.Max Becherer/The Associated Press

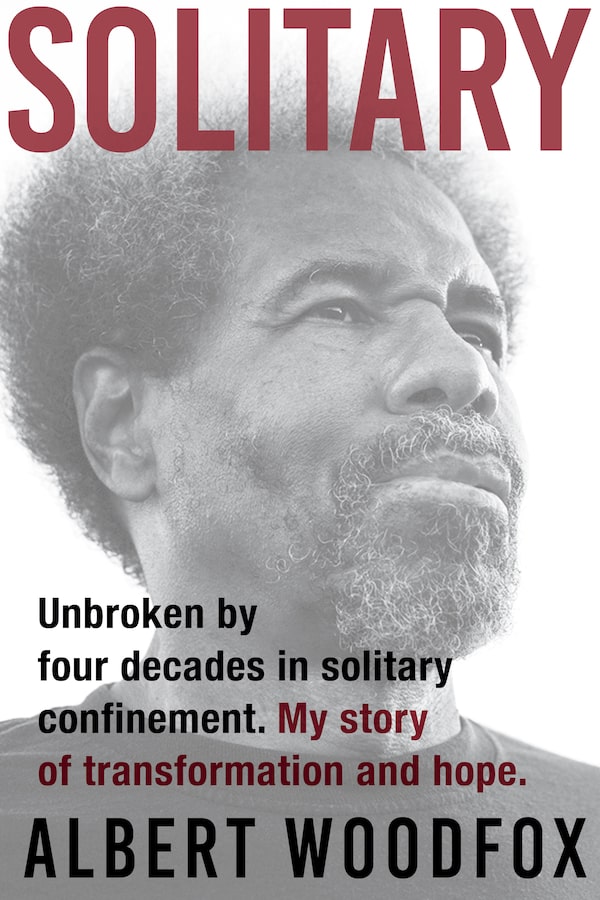

Solitary by Albert Woodfox.Supplied

- Title: Solitary

- Author: Albert Woodfox

- Genre: Memoir

- Publisher: Grove Press

- Pages: 433

Albert Woodfox spent more than 40 years in solitary confinement confronting all manner of predators – sex-crazed inmates, racist guards, stifling heat, wardens bent on breaking his spirit.

But the feature of life in isolation that tormented him most came from inside his own head. Every day he woke up in his six-foot-by-nine-foot cell at Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as “Angola,” and wondered whether this would be the day he’d lose his mind. “Will I start screaming and never stop?” he writes in Solitary, his account of the unprecedented term he spent buried in solitary. “Will I curl up into a ball and become a baby, which was an early sign of going insane? Every day I pushed insanity away. Every day I had to find strength.”

Solitary is evidence of Woodfox’s extraordinary mental resilience in the face of relentless state cruelty. The pacing is brisk, with brief stops to reflect on the United States’ mass incarceration of black people, Woodfox’s black identity and his personal philosophy, much of it centred on the Black Panther Party’s 10-Point Program (“Point One: We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.”). Woven together, these strands form an indictment of the U.S. criminal justice system that should be read for generations.

What keeps the book humming along is Woodfox’s ability to make something good of his stifling surroundings.

To stave off the constant threat of insanity, he mopped, worked out, watched television news and listened to opera. Most of all, he read, devouring the works of Richard Wright, Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey and, for something lighter, the collected works of Louis L’Amour. “I used that space to self-educate myself, I used that space to build strong moral character, I used that space to develop principles and a code of conduct, I used that space for everything other than what my captors intended it to be,” he writes.

Every day, around 80,000 people sit in solitary confinement cells in the United States. In Canada, that figure runs between 1,500 and 2,000. Although segregation conditions tend to be far better here, the horror stories are legion. Only two months ago, a Thunder Bay, Ont., judge released Adam Capay from pretrial custody, ruling that the 1,647 days he’d spent in solitary confinement without adequate mental health care or oversight amounted to cruel and unusual punishment and an affront to the justice system.

But Woodfox is an exceptional case. He spent longer in solitary confinement than any prisoner in U.S. history and somehow emerged undaunted.

The oldest of six siblings, Woodfox robbed, fought and swindled his way to Angola prison by the age 15. He was in an out of jail on petty charges until, at age 18, he was sentenced to 50 years in prison for robbing a bar.

His term in solitary began on April 18, 1971, the day after an Angola prison guard was found stabbed to death. Ample testimony showed that Woodfox was nowhere near the crime scene at the time the guard was murdered, but prison authorities regarded him as a rabble-rouser who’d launched a Black Panther Party chapter inside the prison walls.

Rebranding solitary confinement doesn’t change what it is

Capay’s stay is one more unacceptable consequence of solitary confinement

Adam Capay case shows Ontario must eliminate the inhumane practice of segregation

At the time, J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI regarded the Panthers as a “the greatest threat to internal security of the country” and worked to disrupt chapters across the country.

Investigators pinned the crime on Woodfox and three other prison activists, Herman Wallace, Chester Jackson and Gilbert Montague. Woodfox and Wallace were sentenced to life without parole. The state’s case was so scandalous that even the victim’s widow concluded they were innocent.

Early on in solitary at Angola, the men had no access to books, magazines, newspapers, radios, fans or hot water. Their tier was plagued by rats, red ants and mice. Calling on their Panther principles, the three men organized math tests, spelling tests, martial arts classes and a money pool that spread funds evenly among all inmates in their tier. They filed lawsuits that resulted in improved conditions throughout the state.

Although he exercised his body furiously, he couldn’t escape the early onset of various maladies common among prisoners. One month into his solitary term, he started sweating profusely and felt the walls closing in around him. He recognized it later as the first of numerous claustrophobic spells he would experience during his incarceration. By his thirties, he developed high blood-pressure. In his forties, he was diagnosed with diabetes.

The administration’s scorn for the Panthers never abated. Woodfox was gassed so many times during his first few years that he became immune to it. Although he was non-violent for years, he never had the opportunity to be removed from solitary confinement, aside from a two-year period he spent awaiting a retrial in the 1990s.

Thereafter, a campaign to free Woodfox and two Black Panther friends – the Angola Three – picked up momentum. His conviction was overturned multiple times. The state always countered with appeals until his ultimate release in February, 2016. He describes freedom as "like being newly born. "He had to learn how to use a seat belt, a cellphone and to walk without leg irons. While most survivors of lengthy terms in solitary eschew the complications of their freedom, Woodfox has lectured around the world on the ills of solitary confinement and mass incarceration.

“They did not break me,” he writes. “I bear the scars of beatings, loneliness, isolation, and persecution. I am also marked by every kindness.”

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.