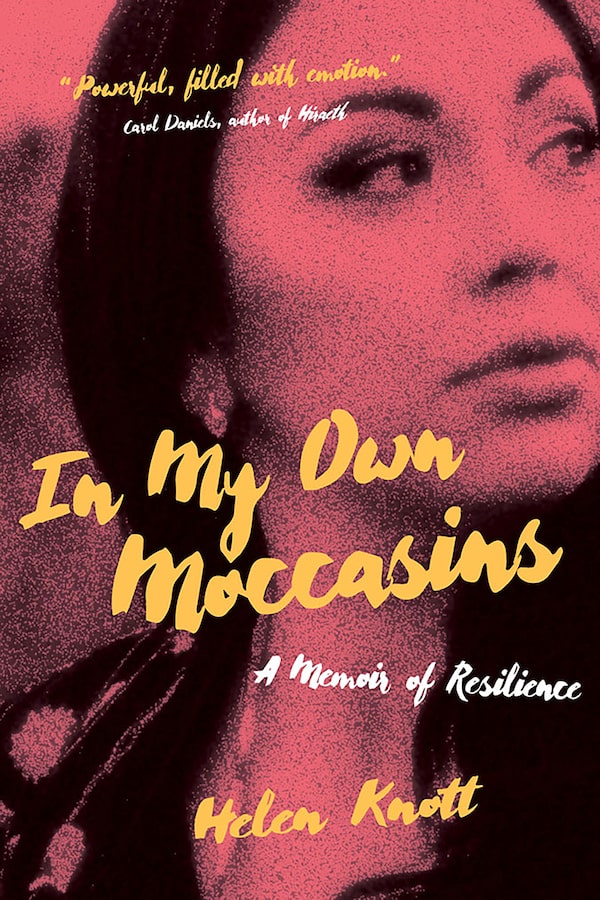

Helen Knott.Supplied

- Title: In My Own Moccasins: A Memoir of Struggle and Resilience

- Author: Helen Knott

- Genre: Memoir

- Publisher: University of Regina Press

- Pages: 366

Although not yet thirty years old, Helen Knott is well known internationally for her advocacy. One of a handful of Indigenous youth invited to speak before the United Nations about how Canada is failing Indigenous peoples, Knott is also a respected environmental activist who has organized nationally against the Site C Dam in British Columbia. In 2016, she was recognized by the Nobel Women’s Initiative through their “16 Days of Activism Against Gender Violence” campaign. Her poetic voice, political insights and storytelling skill place her among a select group of women from around the world committed to peace, justice and equality.

Her memoirs, In My Own Moccasins, build on these commitments, conveying astonishing insights into her experience of being trapped by an abusive addictive lifestyle and by the knowledge of how it played out and wrought devastation in her life.

A member of the Prophet River First Nations committed to defending Indigenous peoples’ rights, Knott’s political message has resonated globally as she insists that there is a connection between violence against Indigenous women and violence against the land. She is an outspoken critic of Canada’s practice of militarizing remote regions, leaving the people and the land vulnerable to exploitation through the agents of resource extraction.

But, as Knott reveals in her book, substance addiction is, like her other foes, an aggressor both intimate and remote. Its predatory vigilance, devious character and relentless self-absorption require its victims to exhaust their energies in the struggle to achieve oblivion by satisfying its appetite. Knott’s memoirs record its promises and betrayals. Her story takes us into the gritty underside of street life in the B.C. towns Fort St. John and Prince George, and Edmonton, Alta., where episodes of “drug-and-sleep-induced” alertness keep at bay nightmares arising from sexual violence, rape and vulnerability. “Expand-contract, expand-contact, expand-contract” serves as an overarching metaphor through which Knott helps her readers approximate addiction’s grasp and the body’s panting struggle to absorb the addict’s self-destructive behaviour.

The memoir conveys insights into Knott's experience of being trapped by an abusive addictive lifestyle and by the knowledge of how it played out and wrought devastation in her life.Supplied

As a writer, Knott is fully aware of what it means to be an addict. It is not for lack of intelligence or a shortage of resolve that Knott cannot escape this condition. For Knott, there is nothing passive about addiction. Its victims cycle through episodes of awareness and sobriety before plummeting back into substance abuse to mute their damaging inner voices and the randomness of overwhelming panic attacks. What unsettles the reader in Knott’s account is her canniness in knowing how to emulate through language the mental immobility of these states and her skill in allowing her readers to feel the helplessness of the victim’s struggle. “During these attacks,” she writes, “it was as if my tongue was going to slither into the back of my throat like a snake in reverse and be the death of me. I would get this overwhelming feeling that nothing in the world was right, and nothing would ever be right. It was in those moments I was at the highest risk of suicide. I could never find the words to formulate the feelings. Instead I would literally bite my tongue."

Silence is an antagonist that Knott’s memoirs struggle against even as she conveys how deeply rooted silence is within Indigenous communities. “I learned it’s better to keep your mouth shut no matter what," she says, when she is beaten for reporting a brutal rape. As silence finds its way into other relationships, we realize the magnitude of its power. The enigmatic “Her,” a friend from adolescence, falls silent and bangs her head against the wall in despair when Knott calls to recount that she has been raped. Knott’s mother turns away after admitting that she and Knott’s father suspected that a family member was sexually molesting her when she was a toddler. Knott describes her own loss of language and descent into “a howl” when she learns that her young cousin has been raped. While she expresses grief and outrage at the pervasiveness of sexual violence and its implication as a cause of her substance abuse, Knott also has the courage and tenacity to fight against it. Her strongest message is that Indigenous women must speak up and break their silence. Suffering in isolation or engaging in self-blame or hijacking one’s outrage through shame worsens one’s condition and leads to self-abnegation.

Self-expression, for Knott, is a path to healing. The memoirs include poems to inspire others and vignettes about rehab that provide a window into her personal experiences. “Life in this colonial state has been our great unknowing," she observes, to lend credibility to her assertion that Indigenous peoples must speak out. In recognizing this condition, her memoirs provide an intelligent, courageous, emotionally searing account of what it means to be substance dependent and fully self-aware. It should be read widely by people who wish to understand and work against the stereotypes that plague individuals who are neither passive nor ignorant about the toll that addictions and social silencing take.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.