Author and playwright Emma Donoghue in Stratford, Ont., on Aug. 26.Christopher Katsarov/The Globe and Mail

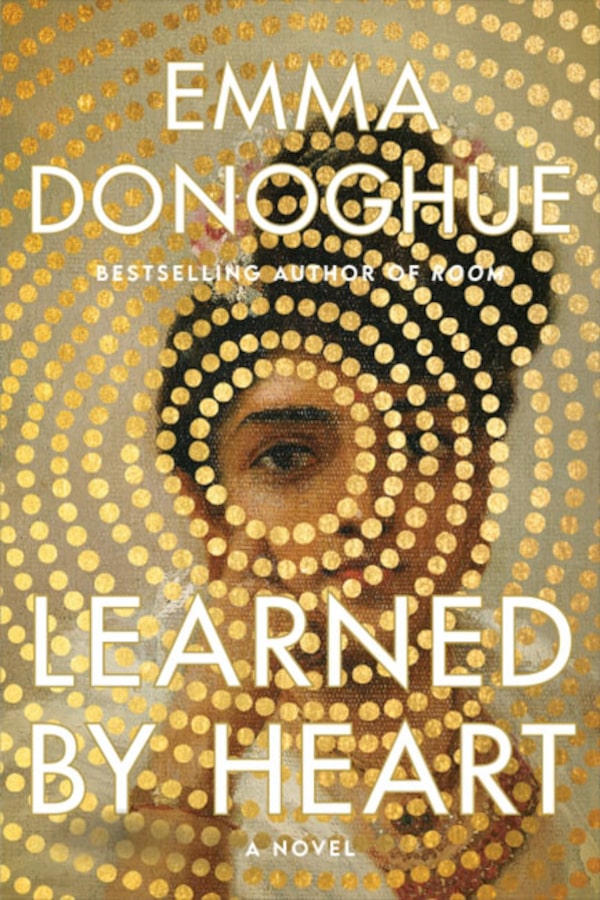

- Title: Learned by Heart

- Author: Emma Donoghue

- Genre: Historical Fiction

- Publisher: HarperAvenue

- Pages: 336

As much as the publication of a deeply researched historical novel from Emma Donoghue has come to seem like an annual event, her latest, about the hidden love between two 14-year-old girls at a Yorkshire boarding school in the early 1800s, was in fact decades in the making.

Read an excerpt of Learned by Heart

Handout

Donoghue credits her 1990 bookshop discovery of the “decoded” journals of one of her two protagonists, Anne Lister (upon whom the HBO-BBC series Gentleman Jack is based), with jumpstarting her career as an academic and novelist, which has often focused on lesbian narratives. And such is the focus for Learned by Heart.

When Eliza Raine (also based on a real-life person) and Lister, who sets herself apart by mannishly going by her surname, initially meet in the novel, it’s as fellow misfits. Under the guardianship of a family friend since the death of her British father, who met her Indian mother while working and fighting in that country for the East India Company (an arrangement then euphemistically referred to as a “country marriage”), Eliza is acutely conscious that her brown skin sets her apart.

It doesn’t help that she’s been made to sleep alone in the attic of the dilapidated pile known as the Manor School, where the only place she can stand up straight is in the middle of the room. Which isn’t to say the school is cruel or abusive: Many of the women running it would qualify as the 19th-century equivalent of “woke.” When Eliza takes her turn to have tea with the Head, the latter spends much of that time sanctimoniously carrying on about how, to avoid the “stain of West Indian slavery,” she refuses to buy “Blood Sugar.”

Accustomed to her solitude, Eliza is put out when the brash tomboy with a copy of Clarissa tucked in her petticoats shows up at her door and announces herself as her roommate. Hearkening from an old landowning family now hit upon hard times, Lister was homeschooled prior to her arrival at the Manor and seems to know something about everything, whether it be building techniques, royal intrigues, the proper definition of a mutin, or the hideout of local Jews during the Crusades.

At first, that know-it-all-ness rubs her classmates and teachers the wrong way. But Lister’s natural charisma eventually wins most of them over. Having the audacity to question the logic of school rules – whether it’s about crossing one’s legs or the usefulness of rote learning – means she alone gets away with bending, if not breaking them outright. Accustomed to shrinking into the wallpaper, Eliza finds this boldness start to rub off on her, too.

Lister shocks Eliza in other ways as well, including by imagining a future for herself that involves world travel rather than marriage. Lister begs to hear about her childhood in India, and Eliza obliges, finding that what once felt like something to hide has become, instead, an exotic asset. And it turns out they do have some things in common, such as the fact that both their fathers were wounded in colonial battles: Lister’s in Concord, Mass., with the “brave Redcoats,” and Eliza’s in India during the Anglo-Mysore Wars.

And then there’s Lister’s confounding way of talking about herself as “the connecting link between the sexes.” When Lister is assigned to play gender-bending Rosalind in the school’s performance of As You Like It, it’s as if “she was born to the role.”

Like many of Donoghue’s novels, Learned by Heart feels hermetic; the bigger world outside the Manor’s walls, one where Napoleon (also known as “Boney”) “guards the Continent like a great spider,” mostly penetrating through the newspapers Lister picks up during trips to nearby York. Those geopolitics are personalized through the Manor’s French instructor, and possible secret aristocrat, who fled during the regicides and keeps his surname hidden.

Though we know it’s coming, the love story itself is a slow burn, some may feel too slow. Leading up to it, chapters detailing the minutiae of daily life at the Manor – lessons, meals, domestic dramas that pull some girls back home – are interspersed with a series of letters, their tone by turns pleading, frustrated and angry in tone, from Eliza to Lister written eight years later from what we soon glean is an asylum.

What happened in between these two periods is the novel’s main source of tension. But though a twist near the end turns it into something darker and more interesting than your average story of forbidden same-sex love, the novel as a whole is more atmospheric and eddying than propulsive.

One thing Donoghue does handle wonderfully is Eliza and Lister’s unfurling intimacy, their belief that they alone have discovered the magical, almost spiritual universe of love and sex. And yet the analogies Eliza uses to describe her feelings would be familiar to a boarding-school girl from any era: “Lister unsettles and thrills her as if something’s about to topple from a shelf, as if a thunderstorm’s on the way.”

It’s only when when they come across an article about a man charged with, and likely to be executed for, committing “an unnatural crime on another” that dark thoughts intrude upon their idyll: “Might that not be said of us too?” Lister says.

But for once, it’s Eliza who’s sure of herself: “Love,” she reassures her lover, “justifies everything.”