Author Catherine Hernandez at the Factory Theatre in Toronto, on Feb. 10.Galit Rodan/The Globe and Mail

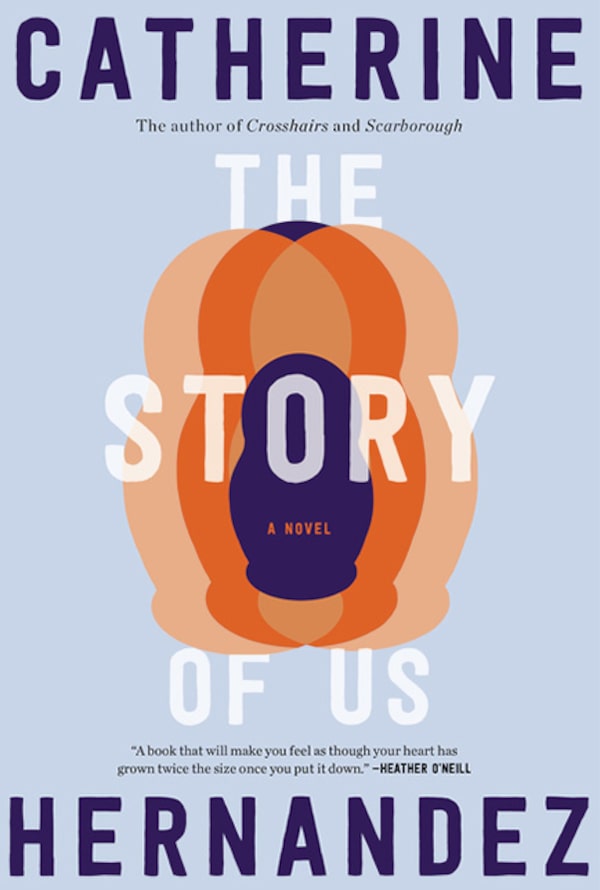

- Title: The Story of Us

- Author: Catherine Hernandez

- Genre: Fiction

- Publisher: HarperCollins

- Pages: 304

I’m haunted by the life of Mary Grace Concepcion in Catherine Hernandez’s The Story of Us.

A Filipina overseas worker, Mary’s transnational journey takes us from Hong Kong and the Philippines to Canada. The accompanying stories of her friends detour us through Europe and the Middle East. As she searches for a means of income to support her family, she’s forced to leave them behind. Hernandez’s novel captures the painful isolation endured by migrant personal support workers (PSW).

The Story of Us is narrated by Mary’s unborn child, one of the “Many Babies” attuned to the corporeal feelings of their mother. This device tunes the readers into Mary’s emotional state. During a moment of strife, one of the Many Babies visits her in a dream: “I’m not [a baby] now,” they tell her. “But I will be one day. Maybe. If I’m lucky, you’ll be my mother.”

This is a reminder for Mary to keep living through a moment of defeat. Hernandez’s narrative compels us to seek out the motivations behind the often harsh realities of migrant labour. It reminds us of the loved ones not yet known – the people some fight for before ever meeting.

Mary leaves behind her husband, Ale, and the epicentre of her support systems. She works diligently to support wealthy and busy families, even on her days off. She is underpaid. She carries the households in which she’s also rendered invisible, helping to raise children before she is callously dismissed.

The goal for Mary is unambiguous. She sacrifices her body, mind and spirit for the possibility of sponsoring and reuniting her family. Mary endures the colossal weight of loneliness. She sleeps in the corners of inhospitable homes. Hernandez forces us to witness the structures of Canada’s immigration system. One begins, or continues, to question: Who is allowed to belong in this place?

Moments of joy and chasmal sadness shape the pages of The Story of Us. For migrants, and their children, Mary’s story would be woefully familiar. For readers aware of how gruesome migration can be for women moving through borders, Mary’s story is not fiction. Hernandez aptly conveys emotional affect in their stories. They are the recognizable women reckoning emotional labour in the parks and sidewalks of Canadian metropolises.

Globally, middle-class and wealthy families rely heavily on the labour of Filipino immigrant women. According to census data in 2008, 10 million Filipino migrant caregivers worked in 197 countries. For centuries, privileged families have depended on racialized women for free or cheap caregiving. Many of these women are shaped by what Saidiya Hartman calls the “afterlives of slavery.”

Supplied

This trend has been a major contributing factor in the formation of many of the diasporas in a “multicultural” Canada. A majority of these women are separated from their families and communities at home. In her first few years of work, Mary doesn’t see Ale for almost three years. She miscarries a child when they meet again. The prolonged distance between them engenders a paranoia of their love waning.

The Story of Us joins a growing canon of fiction and narrative documentary. Hernandez’s novel follows in the footsteps of Makeda Silvera’s Silenced (1992), a narrative about domestic workers who constituted a significant wave of Caribbean migrants in the last half of the 20th century. Silvera’s novel, rejected by local presses, was released after she decided to create a publishing house of her own: Sister Vision Press. Thirty years later, the story of migrant women workers is still being written.

Hernandez’s novel also speaks to the work of Patrick Alcedo’s A Piece of Paradise (2019), a documentary narrating the lives of three Filipina PSWs in Canada, told from the perspective of the child of a former caregiver. Kent Donguines’s Kalang (2020), a term meaning “care” in Tagalog, further furnishes the landscapes of art addressing the stories of the integral and hidden communities that maintain the myth of the Western nuclear family.

Like much of Hernandez’s body of work, Scarborough, Ont., is the backdrop of The Story of Us. It is in the borough where Mary meets Liz, an elderly patient who offers her a way out of her difficulties in Toronto. Mary wanders through Rouge Valley and eastern Scarborough as she finds herself. Her journey brings us back to where Hernandez’s art begins.