Biblioasis

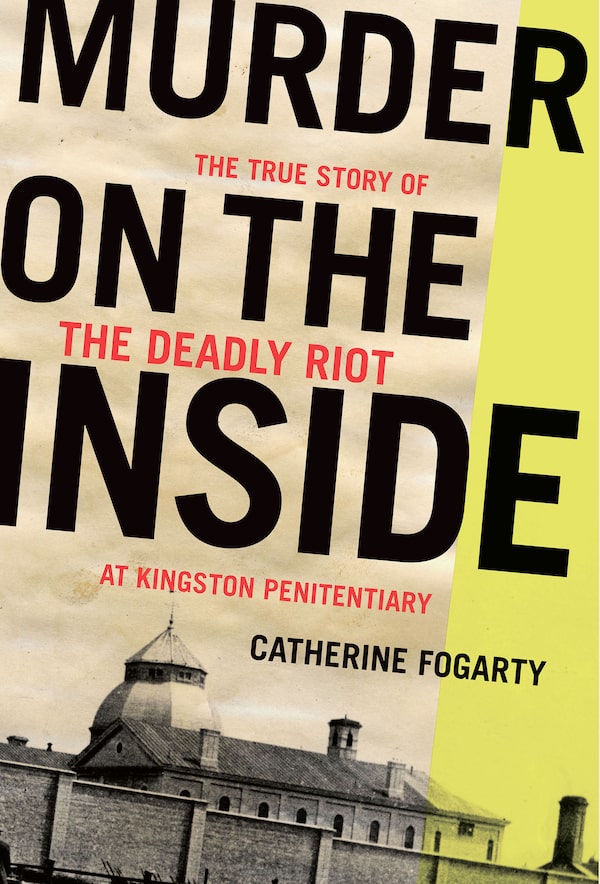

- Title: Murder on the Inside

- Author: Catherine Fogarty

- Genre: Canadian History and True Crime

- Publisher: Biblioasis

- Pages: 312

In 2019, the federal government committed to ending solitary confinement in federal prisons. At the time, critics warned the effort was insufficient. Senator Kim Pate, the former executive director of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies, called the change a mere “rebranding.” Their concerns have proven correct. A 2021 report by Ryerson’s Dr. Jane Sprott and the University of Toronto’s Dr. Anthony Doob found that two years after the government promised an end to solitary confinement, the practice continued. Not only is it ongoing, some instances met the United Nations definition of torture due to the length of time inmates were kept in segregation.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the Kingston Penitentiary riot of 1971. In Murder on the Inside: The True Story of the Deadly Riot at Kingston Penitentiary (Biblioasis 2021), Catherine Fogarty recounts the heavy days, weeks, and months during which inmates launched a prison uprising, took six correctional workers hostage, murdered two fellow inmates and tortured several others, and were tried for their actions.

Canadian Armed Forces troops arrive at the Kingston Penitentiary on April 15, 1971 to help prison officials after inmates took control of the main cell block.Peter Bregg/The Canadian Press

Fogarty opens the book with a précis of the historical moment, writing, “The early 1970s was a time of great political and social upheaval, and what was happening in our prisons reflect that change. Deteriorating prison conditions and the increasing awareness of basic human rights were creating a combustible penal environment both in Canada and south of the boarder. The civil rights movement of the 1960s had given rise to a new breed of inmate – politically aware young men with radical ideas of rights and freedoms. Prisoners wanted to be treated like humans instead of numbers, and they were demanding to be heard.” Reading the first few pages, you see what’s coming. Poor conditions, inmate abuse, understaffing, rising tensions, failed reform efforts, political ineptitude and past riots foreshadow a tipping point. When it arrives, you wonder what took so long.

The uprising is cast in part as a prisoners-rights movement, but it is complicated by internal struggles among inmates. Some, including initial leader Billy Knight, were committed to a non-violent, political struggle while others used the moment for internal retribution. With such a Grand Guignol story, Fogarty might have fallen into the trap that catches so many who write about crime and punishment, transforming flesh and blood humans into stage characters. Instead, she delivers them in three-dimensions, complicated, inconsistent, incomplete, flawed, but human beings who wanted and deserved better treatment from a system designed to make them, as one Kingston Penitentiary warden put it, “dead to the outside world.” Indeed, as Knight himself said, “Kingston was a living, breathing hell-hole and I chose to destroy it before it could destroy me.” Thus we read a detailed, balanced record of the creation of an inmate police force to protect the guards, committees to sort out matters such as food distribution, and a press conference to air concerns and demands, political skulduggery, and gang torture. The book serves as a study of a moment and of its participants, who both reflect the time and transform it as the events of the 1971 riot would contribute to long-overdue penal reform in Canada.

Fire destroys the famous cupola at Kingston Penitentiary.Toronto Telegram / York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections, ASC07602

Where the book is at its best, the reader gets to know the inmates who struggle for power among one another and against the political system that forgot them. We are taken into strategic and tactical debates alongside a citizens’ committee struck to build a bridge between the prisoners and politicians and corrections officials as the crisis unfolds. Fogarty captures the essence of the sometimes-craven but complicated politics of the federal solicitor general, Jean-Pierre Goyer, who tries to navigate a situation along a knife’s edge while Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, away on his honeymoon at the time, is absent. The story even touches on the complications of federalism as three orders of government sort through the usual responsibilities and exigencies of crime, punishment and crisis.

Fogarty could have further strengthened the narrative with more historical context – including a deeper look into the social, political, and economic forces and events that shaped the moment. For instance, what role, if any, did the recent FLQ crisis have on the Trudeau government and its handling of the uprising (for instance, its hesitance to negotiate with kidnappers)? How exactly did the civil rights movement condition political and public reaction to what happened at Kingston Penitentiary? Were there any specific links or commonalities between this riot and the much deadlier Attica Prison riot – which Fogarty briefly discusses – that broke out in September, 1971?

Destruction done to cell-blocks during riot at Kingston Penitentiary on April 23, 1971.John Scott/The Globe and Mail

The book closes with “After Kingston,” a look at the aftermath and reform efforts that followed the uprising. As Fogarty writes, the commission of inquiry into the events determined “the riot was not an isolated incident but part of an escalating series of violent institutional disturbances designed to bring public attention to long-standing grievances that had not been adequately dealt with by the Penitentiary Service.” The commission produced 52 recommendations and, by 1973, Canada had adopted an independent Office of the Correctional Investigator as an oversight agency. But later we read of history as frivolity as the Stephen Harper government adopted a tough-on-crime approach during its years that contributed to overcrowding, inmate violence, rehabilitation programming cuts and increased suffering inside correctional institutions.

Today, Canada is still struggling to live up to the principles of justice, fairness and decency we are told form the backbone of the country. Yet we replicate analogues of injustice centuries old, even as we stare down stories that remind us that, for all the progress we claim, we have not escaped our past. Maybe this decade or this century will bring a serious discussion and consideration of the limits and even the end of the carceral state. Reading Murder on the Inside, however, there are moments when it seems we are closer to the era that Charles Dickens described when he visited the Kingston Penitentiary in 1842 than the enlightened ideals we claim for ourselves today.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article incorrectly said that Drs. Doob & Sprott conducted a study for John Howard Canada. This version has been corrected.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.