Supplied

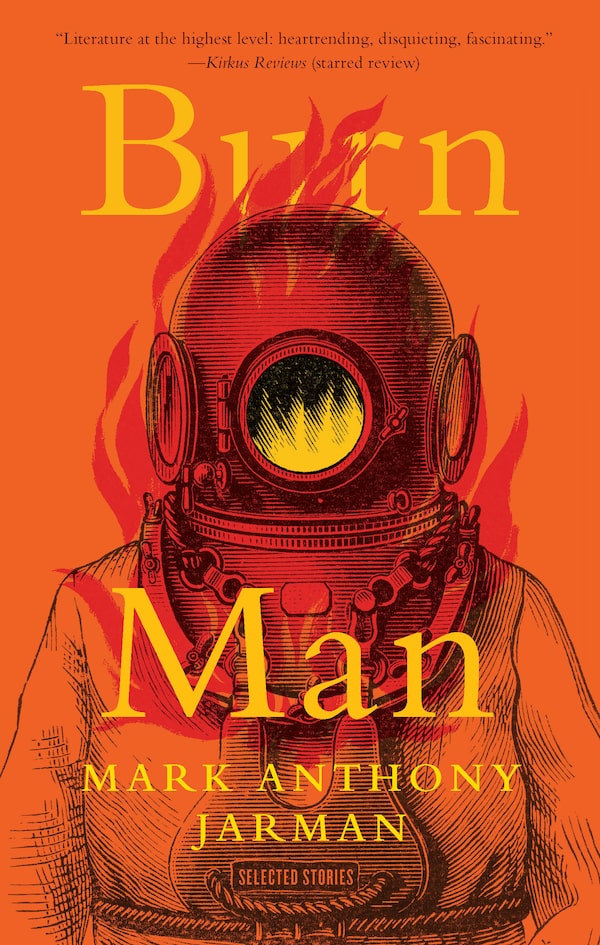

- Title: Burn Man

- Author: Mark Anthony Jarman

- Genre: Fiction

- Publisher: Biblioasis

- Pages: 320

For 40 years now, Mark Anthony Jarman has been writing sad songs and waltzes for cowboys, drifters and hockey fans. Not actual songs, but stories with a flair for the musical – both in terms of the way a near century of rock ‘n’ roll weaves in and out of the lives of his mostly extremely hard-luck characters, and in terms of the writer’s own exquisite ear for the exhilarating, incantatory properties of language.

Jarman’s ardour for the way a rare word can slide smoothly into a sentence is particularly remarkable; his new collection of selected stories, Burn Man, had me running up against the dictionary’s paywall more than once. Merriam-Webster, for what it’s worth, will define more than 200,000 words for free, but the rarest ones are withheld for subscribers. Beware, neophytes: Jarman’s logophilia may prove both contagious and costly.

Book recommendations from Globe staff and readers

Burn Man offers pleasures beyond expanding one’s vocabulary, though readers invested primarily in plot, character development or an easy-to-follow chronology might disagree. Likewise readers who are disinterested in a writer who seems to go out of his way to find interesting ways to injure, kill or generally vivisect the minds and bodies of his characters might find Jarman’s work garish, or even grotesque.

But for those with a strong enough stomach, Jarman’s fascination with the gruesome and macabre isn’t uniformly tedious. The title story, for example, is sublime. Burn Man on a Texas Porch begins with the morning the narrator awakes to find himself on fire, a near-lethal miscommunication of some kind having taken place between his propane tank and his camper van. “I sprang from sleep into my new life on my feet in front of a befuddled crowd, my new life on fire,” Jarman writes, in the near middle of the long first sentence, which begins with propane and ends with sudden, senseless guilt, of the identifiably Catholic variety, “thinking, Now I’ve done it, and then thinking Done what? What have I done?”

In this story and others Jarman works a particular magic, folding the events of a life back on themselves, capturing a consciousness that is never quite able to be still, to be firmly in the present. Even when the narrator awakens to his “new life,” the old one hasn’t exactly gone up in smoke; we get the sense his story has more than one origin.

Since the day of the burning, the narrator has started thinking of himself in the third person, christened himself Burn Man and started listening to “Johnny Cash’s best known ballad.” Then we learn that, as a child, Burn Man “haunted libraries,” a horn-rimmed student of history. He loved reading about Canadian soldiers in the Second World War, about sailors whose oil ships caught fire.

Jarman echoes Cash’s famous phrase to describe historical sailors and a flaming freighter, the call back a satisfying nod buried in horror: “circular scalp of sea on fire and framing crude races right at them, so eager, enters them, fricassees their lungs and face and hands, the burning ring of fire come to life on the Murmansk run.”

Mark Anthony Jarman’s ardour for the way a rare word can slide smoothly into a sentence is particularly remarkable.Muhammad Al-Digeil/Supplied

Burn Man’s new life on fire may have started the day the camper van blew, or in the library, or, maybe, one night in Texas, when a woman taught the narrator how to kiss and be kissed in yellow porch light while a taxi waited for the lovers to separate, ready to take him away. “In that instant, I was changed,” Burn Man confides. Desire, too, is a flame that licks.

Desire is an animating force for many of the stories here, perhaps most obviously in one of the three-story cycles that make up the bulk of the selection. The more amorous story cycle follows a recently divorced man through Italy, at an art school in Rome and on traumatic day trips through Naples. Knife Party sees the man and his cousin, Eve, a young woman whose nearness begets a kind of intimate longing, experience the threat of violence on a train ride. Later, at a house party, the threatened terror is realized as they witness a man bleed to death. Someone has stabbed him in the leg, severing an artery.

In the cycle’s second story, Pompeii Book of the Dead, the same narrator ruminates on his lovely cousin and distant ex-wife as he walks the streets in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, fascinated with both the volcanic ruins and life among the locals and tourists built on top of the ashes: “The excavations are fantastic, but locals must resent this favoured twin, this magnet shadow so close to them.” Doubles permeate Jarman’s work; his characters are continually caught between what is and what might’ve been, life in the moments of before and after, a perpetual bouncing echo between “now I’ve done it” and “what have I done?”

The second story cycle is a historical fiction set on the prairies in a decade roughly defined by the Battle of Little Bighorn and the execution of Louis Riel – Jarman memorably describes Riel hanging by the scratchy rope for two minutes before “his little mutiny at the edge of the world is over, a brief empire dismantled.” The first story, Assiniboia Death Trip, an adulterous love story set among endless gruesome battles, contains an uncommonly sharp definition of colonial logic, of frontier thinking: “Red sunsets, smoke and grey fire; we are remaking the world, scorching it, cooking it, burying our face in pillows.”

By the end of the book, the Assiniboia and Italy story cycles eclipse. In the final story of both the collection and the Italian trio, The Hospital Island, Eve and the divorced narrator sit on his apartment balcony, with a vantage over the Vatican walls in Rome, and toy with a certain idea: “Eve becomes more and more certain that I can be the first Canadian pope (I wonder, can we count Louis Riel as a pope of Assiniboia?).” Later in the story, Eve and the narrator attend mass, with nonnas chanting and Croatian women singing hymns.

They, like Jarman, are able to weave between irony and sincerity. Jarman’s stories on the whole feel less Catholic in the Roman sense and more Catholic in the Greek sense: his attentions are rangey, all-embracing, vitalized by the splendour both in ugly mundane violence and the febrile pulsations of longing, of something a bit like love.