Author Jeannie Marshall.DA Cooper

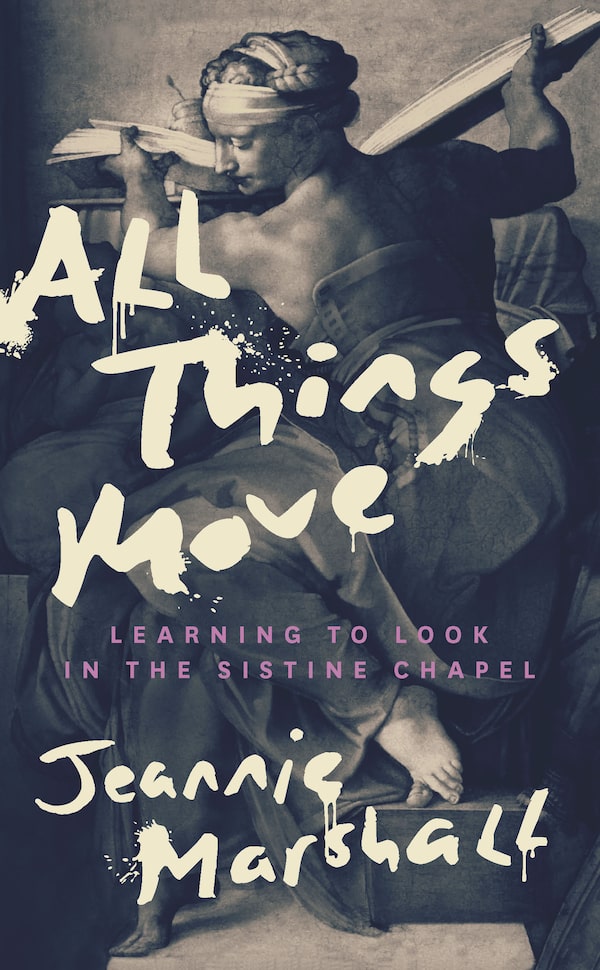

- Title: All Things Move: Learning to Look in the Sistine Chapel

- Author: Jeannie Marshall

- Genre: Non-fiction

- Publisher: Biblioasis

- Pages: 240

Canadian writer Jeannie Marshall once overheard a tourist in the Sistine Chapel exclaiming to her companion, while pointing out the scenes she recognized from reproductions, “Look at that, that’s famous! And there, that’s famous,” and “Oh, and that one’s really famous.” Every day thousands of visitors enter the chapel to admire the frescoes painted by Michelangelo in the 16th century. Depicting more than 300 Old Testament and classical figures on the ceiling and a vision of the Last Judgement on the altar wall, these are among the most celebrated artworks in the Western canon. Like that excited tourist, the crowds are there simply because the frescoes are famous.

All Things Move by Jeannie Marshall.Supplied

But why are they famous? Do they deserve their reputation? What do they mean to modern viewers who have no religious affiliation? What did they mean to the devout of their own era?

Living in Rome but initially reluctant to engage with the Sistine Chapel, Marshall eventually decided she would wrestle with its reputation. Unable to grasp its entirety in a single visit, she found herself returning again and again, finally profiting from the rare opportunity that the pandemic provided to see the frescoes at her leisure without the crowds. Her new book, All Things Move: Learning to Look in the Sistine Chapel, is primarily a philosophical consideration of what attracts us to art, what role it plays in our lives.

Marshall describes herself as an atheist and goes to admirable lengths to understand the universal themes in Michelangelo’s figures and scenes. She parses the gestures of the sibyls or the moods of the prophets with acute insight to demonstrate how they communicate familiar human behaviours across centuries. But she also finds that the frescoes, produced in an era of intense faith, are a consideration of time and civilization so vast that their meaning seems beyond reach. “The Sistine Chapel comes from a world before us with our twenty-first-century preoccupations, where we don’t really believe that art can do anything to us, but we come to see it anyway, just in case.”

After this rather abstract, albeit personal, rumination on the power of the Sistine Chapel frescoes, Marshall reveals that while she has no faith, she does have an unpleasant history with Catholicism. Specifically, her mother was a woman impoverished and oppressed by the Catholic Church’s prescriptions against divorce and birth control.

Marshall grew up poor in small towns north of Toronto before the family moved to the city, where her widowed mother raised six children. Eventually Marshall escaped by taking university night courses while doing clerical work, then pursuing a career in journalism. She has, on the one hand, good reasons to detest Catholicism and, on the other, long familiarity with its icons. Some more foreshadowing of this history in the book’s early pages might have made her Sistine Chapel pilgrimage more gripping.

Once she has revealed her personal history, however, she turns to consider the world in which the Sistine Chapel was painted. Here her approach, dispassionate yet empathetic, serves her particularly well. She considers the political atmosphere of Renaissance Rome, where Michelangelo operated in an atmosphere of intellectual inquiry that made powerful connections between ancient and Christian philosophies, yet where the Church’s lavish artistic programs were underwritten by the notorious practice of selling indulgences to the faithful.

When the mutinous mercenary army of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V sacked Rome in 1527, raping, looting and killing, it was enraged partly because the army had not been paid and partly by the sight of the Catholic extravagance that the new Protestantism was railing against. Michelangelo’s altar wall Last Judgement, a much darker scene than the Old Testament precedents he had painted on the ceiling, was created in the 1530s in the aftermath of a traumatic attack that had decimated Rome’s population, and challenged its beliefs. Imagining the faith and the outrage on both sides, Marshall places these enduring images in a rich historical context, revealing what they must have meant to their contemporaries.

Her 21st-century experience, by contrast, is anchored by her book’s photographs from Douglas Anthony Cooper, provocative images of contemporary Rome where ancient streets and historic buildings provide a backdrop for graffiti, buskers and heedless passersby.

In the era of the perpetual scroll, art still asks us to stop and look, long and slowly. All Things Move is a rich vindication of one writer’s decision to do just that.