Left: The house is built on curved steel structural elements fabricated by the Eppich brothers’ company. Right: Erickson’s design has the house step waterfall-like down its site on a West Vancouver hillside.Geoffrey Erickson/Figure 1 Publishing

Eppich House II by Greg Bellerby.Figure 1 Publishing

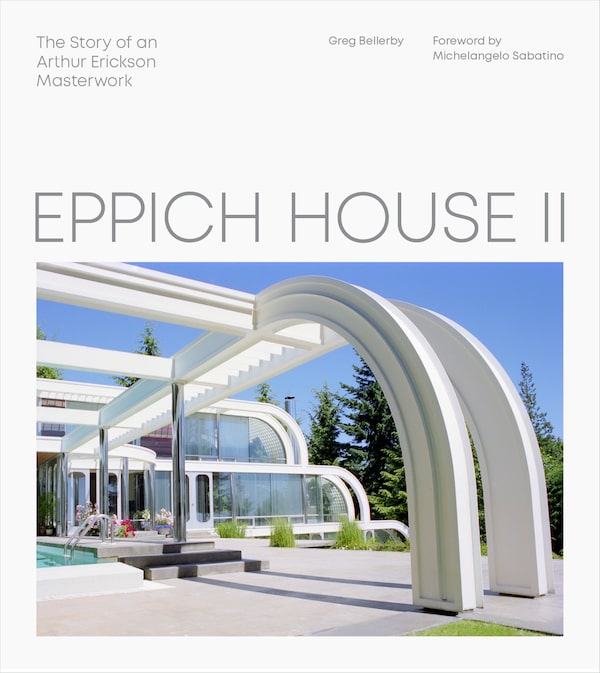

- Title: Eppich House II: The Story of an Arthur Erickson Masterwork

- Author: Greg Bellerby

- Genre: Non-fiction

- Publisher: Figure 1 Publishing

- Pages: 160, $45.

A “masterwork.” That’s what author Greg Bellerby calls this house by Arthur Erickson in West Vancouver, a hillside aerie in white steel and glass block. He’s right, and this coffee-table book, Eppich House II: The Story of an Arthur Erickson Masterwork, is beautifully presented and clearly and thoroughly written. Most important, it makes a strong argument for this house by one of Canada’s great architects.

The house, which Erickson designed in the late 1970s and completed in 1988, is a late-Modernist jewel; it uses a bold steel structure to frame a complex and nuanced set of domestic spaces. And its future is uncertain. It was never open to the public and is now up for sale by its original owners. It reflects a very specific moment in design history. Its interiors, including custom furniture designed by Erickson and his partner Francisco Kripacz, have an eighties chrome-bling sensibility that is both gorgeous and, to some eyes, dated. The house is going to need public attention in order to find an owner who truly appreciates what it has to offer.

Erickson, who died in 2009 at the age of 84, was the best-known, and arguably the best, Canadian architect of the 20th century. He did much of his most memorable work in private houses, particularly for clients who allowed him the budget and freedom to create.

He found those in the Eppich brothers: Helmut and Hugo, who emigrated from what is now Slovenia to Germany and then to Canada in the early 1950s. The two brothers founded Ebco Industries, a metal-fabrication company that produced machinery for the mining industry and aerospace – including components for the Canadarm on the International Space Station.

The gardens by Cornelia Hahn Oberlander are carefully integrated with the architecture.Geoffrey Erickson/Figure 1 Publishing

Each of the brothers, together with their respective wives, hired Erickson to design a house, and put Ebco’s expertise at his disposal. Helmut and his wife, Hildegard, were first, in 1972, with a four-level concrete house designed to showcase the paintings of the Eppichs’ older brother, Egon. Hugo and his wife, Brigitte, followed. The two brothers were serious patrons of architecture. Bellerby quotes Hugo discussing the complexities of building his own house: “I want Erickson’s design – the way Erickson sees it. How the trades will do it, that should be the trades’ problem.”

This is the kind of thing every architect dreams of hearing. Erickson had already advanced his art with a series of house commissions over the previous decade, particularly his 1965 house for Gordon and Marion Smith, which reinterprets the wood post-and-beam structure of Japanese temples into a modern glass house. The essence of what he was as an architect was created in the houses, Bellerby argues.

Indeed, many of the characteristic elements of Erickson’s work show up at the Eppich House II. There is technical innovation, in the design of the building’s structure and in the furniture, There is a close connection between architecture and the surrounding landscape, which was designed by Cornelia Hahn Oberlander. (“To me,” Erickson is quoted as saying in the book, “architecture means unifying the duality of site and building.”) And the structure of the house is revealed and given a poetic expression. Specifically, curved steel members – produced by Ebco – give the house its form. They course down the hillside like a waterfall made solid.

It’s easy enough to connect this gesture to some of Erickson’s best-known public work, as Bellerby does: the Law Courts complex at Robson Square in downtown Vancouver, for instance, an architectural project closely integrated to its site, and defined by a literal waterfall. Or the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, in which Erickson took the post-and-beam structure typical of Haida houses and imitated it in massive, expressive concrete.

Erickson and his partner, the interior designer Francisco Kripacz, designed custom furniture for the house.L: Roger Brooks; R: Geoffrey Erickson/Figure 1 Publishing

That was only one of many allusions and references in Erickson’s work. He borrowed from the architecture of different periods and places, from ancient Rome to contemporary Kyoto. Scholar Michelangelo Sabatino, in his foreword to Bellerby’s book, says Eppich House II “is both local in its relationship with the land and cosmopolitan in its formal and material associations.” Sabatino links the house, convincingly, to the work of both Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright.

That’s quite the range. It reflects Erickson’s changeable and responsive sensibility. And it aligns Erickson with this moment in architecture; today many younger designers are ready to mix new and old and regard Modernism as simply part of a long historical chain. He is ripe for discovery by a new generation.

Bellerby’s book is not alone in doing this sort of work. There is a broader effort now under way among historians and scholars to contextualize postwar architecture in Canada. both for a scholarly audience and the wider world. Some of the Eppich house’s Vancouver-area cousins have gotten close looks through the West Coast Modern House Series, a group of detailed monographs coordinated by the University of British Columbia’s School Of Architecture And Landscape Architecture.

Eppich House II, the building, deserves to be considered in its historical context. Here’s hoping its next owners have this book on their glass coffee table.

Alex Bozikovic is The Globe and Mail’s architecture critic.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.