At the start of her vibrant memoir 'Old in Art School,' Nell Painter finds that being on the older end of midlife has become an inflection point for new creative desires.

No one wants to die young, yet no one wants to be elderly and indigent. This is the conundrum of growing older: Instead of revelling in the prospect of a long life, we rue the passage of time and worry endlessly about the future. To be young is to look optimistically forward. Middle age has no sunny vistas, just the inevitable decay of body and mind, perhaps a marriage made dull from repetition or a bitter divorce, the care and feeding of parents that have become our children. Time, in short, when the losses outnumber the gains.

It shouldn’t be this way, of course, and three new books offer a bracing reminder of why middle-age can be something other than the final furlong, but instead a time for liberation and self-renewal. At the start of her vibrant memoir Old in Art School, Nell Painter finds that being on the older end of midlife has become an inflection point for new creative desires. A prolific author and a tenured professor of American history at Princeton, 64-year-old Painter longs to explore her dormant ambition to become an artist, plugged not into ideas about art, but the actual thing itself. Enrolling in the Masters of Fine Art program at the Rhode Island School of Design, Painter is at home in a classroom but feels a chill from her teachers and fellow pupils. Is she too old to be accepted into a culture that worships callow novelty and a milieu in which relatively few black artists have been admitted into the canon of great American Art?

Her advanced age makes her self-conscious. "I imagined,” Painter writes with typically elegant candor, “my fellow painters lolling about together … young enough for exemption, fresh enough not to owe alcohol’s tax in sleeplessness and looking totally rotten in the morning.” Despite this generational disconnect and a severe distaste for faddish critical theory, Painter finds deep pleasure in learning how to paint and draw, as she is forced to exchange book knowledge for instinct in order to tell visual stories. “I concentrated on what I could see and the art I could make,” Painter writes. “I felt free.”

Disdainful of marketplace expectations and the merciless commercial gaze of an art world that would view her as anachronism, Painter is intent on finding her own artistic breakthrough. It doesn’t come easy; she is insecure about her drawing skills, initially fumbling her way through, only hitting her stride when she frees herself of unreasonable expectations and approaches her art as a channel to something deeper. Old In Art School, which is as beautifully rendered as Painter’s art, is inspiration for those who think they have left the best of themselves far behind. As it turns out, Painter’s new ways of seeing become a power-boost for her work as an historian: “Now with images in my eyes, I wanted to ask questions even when I knew I could not answer them, but when the mere asking let me focus my attention on particular individuals in the past.”

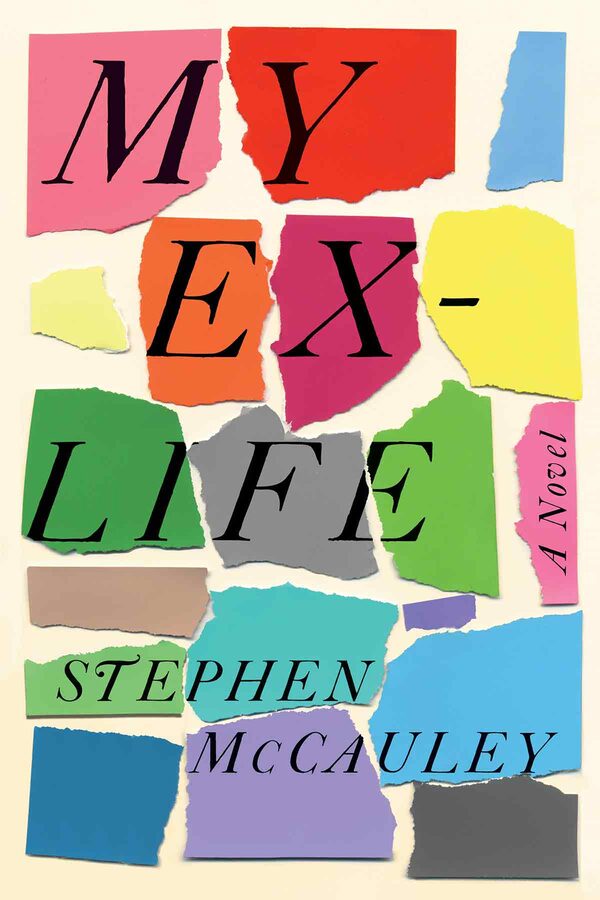

Stephen McCauley’s witty and tender-hearted novel 'My Ex-Life' features Julie Fiske, a 50-ish protagonist just trying to hold onto what she has scrabbled to earn.

Instead of venturing out like Painter, Julie Fiske, the 50-ish protagonist of Stephen McCauley’s witty and tender-hearted novel My Ex-Life, is just trying to hold onto what she has scrabbled to earn, and suffers the prospect of entering her dotage without little to show for it.

Her ex-husband Henry is about to sell the New England house that she and her daughter Mandy live in, a portion of which Julie has transformed into an Airbnb in order to supplement her income as an art teacher. At the same time, her first husband, David, a college admissions coach who came out as gay after their failed marriage, is mourning the loss of his boyfriend, who has left him.

McCauley’s characters find strength in enduring friendship, a virtue that’s perhaps best appreciated when shared by older ex-partners. When Julie hires David to tutor her aimless daughter, he sees an opening for redemption, a chance to heal old wounds. Julie, to her relief and delight, finds herself drawn to David’s kindnesses and their shared history – tiny but satisfying sparks of recognition that console them even as the difficulties pile up. David takes the news of his boyfriend’s impending marriage while feeling “loved” by Julie “and, maybe more important, able to be loving without … the complications and dirty laundry of sex.” What resonates in My Ex-Life is the pull of affable companionship between two people with memories to share, and the deeper satisfaction of mutuality over physical intimacy.

The theme of divorce also plays heavily in 'The Cost of Living,' a flinty and moving memoir from writer Deborah Levy.

The theme of divorce also plays heavily in The Cost of Living, a flinty and moving memoir from writer Deborah Levy, who regards her former marriage as entirely lacking compatibility, an effacement of her identity. Newly divorced and living alone, she reclaims herself from the “societal story” that has denied middle-aged women the right to revel in the same appetites and desires as their younger selves. Her route to freedom comes through renewed dedication to her craft while enduring the privations of a damp garden shed, enjoying her peregrinations on an electric bike, tending to herself and her needs. Levy finds strength in rejecting the patriarchal clichés that regard divorced women as “crazed with suffering” and “viciously self-hating.” Better for her to wade through the “black and bluish darkness” than reach for the cold comfort of victimhood. Like Painter, middle age for Levy isn’t a third act; it’s a prologue to an entirely new adventure.