Sign up for our Books newsletter for the latest reviews, author interviews, industry news and more.

- 📖 Fiction

- 📖 Non-fiction

- 📖 Picture books

- 📖 YA & middle grade

New this spring

Fiction

Whereabouts, Jhumpa Lahiri (Penguin Random House, April)

In this melancholic, reflective novel about a woman living alone in an unnamed Italian city, the Pulitzer Prize-winner has effectively played a game of literary telephone with herself: Lahiri originally wrote the novel in Italian – a language she only acquired fluency in after moving to Rome about a decade ago – then translated it back into English.

Sufferance, Thomas King (HarperCollins, May)

Jeremiah Camp, a.k.a. The Forecaster, had the unique ability to find opportunities for billionaires-in-the-making before he hung up his prognosticating hat to beat a silent retreat – literally, he’s mute – to an abandoned residential school on a tiny reserve. Now, in a cuttingly satiric take on a familiar trope, the head of the consortium Jeremiah used to work for has come a-knocking: Billionaires are dying, and he needs Jeremiah to play oracle one last time.

Second Place, Rachel Cusk (HarperCollins, May)

Cusk’s first novel since her Outline trilogy is another brooding tour de force. A woman, known only as M, invites an artist, L, to stay at her and her husband’s guest cabin, their “second place,” on the remote marsh where they live. But instead of providing M with yearned-for insights – L’s work had profoundly affected her years previously – the artist shows up with an attractive young girlfriend and a strange, unsettling dynamic takes hold between couples.

The Willow Wren, Philipp Schott (ECW, March)

Based on a true story, German-born, Winnipeg-based Schott’s Second World War-set sophomore novel is told through the eyes of sensitive, awkward 11-year-old Ludwig, who, after suffering abuse at a Hitler Youth Camp, is forced to help his dispirited mother and three siblings escape Russian occupation in the wake of his Nazi father’s death.

Peaces, Helen Oyeyemi (Hamish Hamilton, April)

In books, song and film, trains have always had the edge over other modes of transportation when it comes to evoking the mythic. Still, few have taken the train journey to the heights Helen Oyeyemi has in her slippery, surrealist seventh novel, in which Otto and Xavier – boyfriends who take a “non-honeymoon honeymoon” by rail through the English countryside – encounter a series of enigmatic passengers with whom they seem to a share a past.

Return of the Trickster, Eden Robinson (Knopf, March)

Leavened, as always, with sassy, mock-heroic wit, the conclusion to Robinson’s landmark trilogy begins with Jared, teen trickster spawn of Wee’git, waking up in hospital following an epic battle with his ogress-aunt Georgina. When she returns here for the final confrontation Georgina assumes the form, briefly, of a 10-foot-high chicken.

The Sister’s Tale, Beth Powning (Knopf, May)

In 1880s New Brunswick, with an axe murderer on the loose, Josephine Galloway, the wife of a roving sea captain (himself the nephew of the titular heroine of 2010′s The Sea Captain’s Wife), saves an orphan girl from the clutches of depraved townsfolk and ends up the proprietor of an all-female-run boarding house. Powning’s approach to historical fiction is, as ever, tactile and immersive.

Swimming Back to Trout River, Linda Rui Feng (Simon & Schuster, May)

In Feng’s quietly assured debut, which weaves between the Cultural Revolution and its aftermath, 10-year-old Junie, born without legs, is living contentedly with her grandparents in an idyllic Chinese village when a letter arrives from her father, assuring her he will bring her to join him in America before she turns 12. What he doesn’t say is that her parents, riven apart by old scars in their new home, are now estranged.

Nothing the Same, Everything Haunted, Gary Barwin (Penguin Random House, March)

The author of Yiddish for Pirates proves again why he’s one of the most distinct voices in Canadian lit by introducing us to Motl, a middle-aged Jewish would-be cowboy – ”a Quixotic Ashkenazi of the bronco” – who embarks on a quest across Europe after the Nazis invade his native Lithuania in 1941. His mission? To retrieve the family jewels – a.k.a. his testicles, shot off in the previous war.

Half Life, Krista Foss (McClelland & Stewart, March)

The protagonist of this restless and absorbing novel is Elin, a beleaguered Milwaukee high-school physics teacher and single mom who’s forced to confront past trauma and her own troubled relationship with her mother and siblings after her father, a revered Danish furniture designer, suddenly dies. Foss has a knack for vivid phraseology; to wit: Elin’s mother has a face “like a freshly bombed church.”

Everyone Knows Your Mother is a Witch, Rivka Galchen (HarperCollins, June)

In 1618 Germany, an elderly widow is accused of witchcraft after her herbal concoctions make the glazier’s wife ill. Desperate, Katharina Kepler summons her brilliant son Johannes – he of the planetary motion laws – from the imperial court. With its conflagration of plague and impenetrable groupthink, Galchen’s darkly funny tale, based on historic records, is at times achingly resonant.

The Living Sea of Waking Dreams, Richard Flanagan (Knopf, May)

In his eighth novel, the Australian Booker-winner (for The Narrow Road to the Deep North) joins the ever-growing chorus of writers tackling environmental devastation in the Anthropocene. As three siblings debate their 86-year-old mother’s right to die around her hospital bed, trees and birds burn outside, while daughter Anna’s limbs, in a magic-realist turn, start to vanish.

This Eden, Ed O’Loughlin (House of Anansi, June)

O’Loughlin – shortlisted for the Giller for Minds of Winter – returns with a David Mitchell-inspired intercontinental tech thriller set across Jerusalem, Alexandria, New York, Uganda and Ireland. After the coder girlfriend of a Vancouver gig worker suddenly dies, the latter gets pulled into a global cat-and-mouse game involving a Silicon Valley mastermind, the deadliest weapon ever made and a female spy named Aoife.

The Octopus has Three Hearts, Rachel Rose (Douglas & McIntyre, March)

A woman is comforted by a family of rats while recuperating from a stabbing attack, a convicted sex offender living under a bridge takes in a suicide’s dog – the characters in the Vancouver poet laureate emerita’s visceral collection of stories, most of whom live on the fringes or are coping with trauma, have something in common: They all seem to connect better with animals than with their fellow human beings.

Non-fiction

A Ghost in the Throat, Doireann Ni Ghriofa (Biblioasis, June)

Dubbed “sumptuous, almost symphonic, in its intensity” by The Sunday Times when it was published last year in the U.K., this genre-bending book interweaves a chronicle of the author’s fraught experience of early motherhood with an account of her obsession with Eibhlin Dubh Ni Chonaill, an 18th-century noblewoman whose blood-soaked lament for her dead husband is considered one of the greatest Irish poems of all time.

Norman Jewison: A Director’s Life, Ira Wells (Sutherland House, May)

The U of T academic’s first book aimed at a popular audience uses extensive archival research and dozens of interviews as the basis for a deep dive into the career and tribulations of the idealist Canadian director who, despite working with Hollywood’s biggest talent on some of the most iconic films of all time, rarely got the respect he deserved “in an industry increasingly captive to corporate greed.”

Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty, Patrick Radden Keefe (Doubleday, April)

An 850-page “secret history” is bound to have a lot of secrets, and indeed, the National Book Critics Circle Award- and Orwell Prize-winner has penned a truly explosive exposé about the pharmaceutical family – known less these days for their lavish patronage of the arts than for the role their signature product, OxyContin, played in the opioid crisis, and the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

Anything But a Still Life: The Art and Lives of Molly Lamb and Bruno Bobak, Nathan M. Greenfield (Goose Lane, March)

Expressionist painters Lamb and Bobak first rose to prominence as war artists in the 1940s – he was one of the youngest, she the only official female – and would go on to become key figures in 20th-century Canadian art. Greenfield gives a nuanced assessment of their individual work and styles, and, through Lamb’s diaries, a portrait of a tempestuous 50-year marriage.

The Bookseller of Florence: The Story of the Manuscripts That Illuminated the Renaissance, Ross King (Grove Atlantic, April)

The Governor-General’s and Charles Taylor Prize-winner paints a rich portrait of Renaissance Florence at the height of its splendour through the story of manuscript dealer and “merchant of knowledge” Vespasiano da Bisticci, who, after entering the book trade at the age of 11, produced hundreds of exquisite manuscripts for Europe’s most famous and powerful personalities just as the printing press was set to disrupt bookmaking forever.

The Devil’s Trick: How Canada Fought the Vietnam War, John Boyko (Knopf, April)

When it comes to their country’s role in the Vietnam War, most Canadians are apt to conjure the 30,000 war resisters who poured over our border, not the 20,000 Canadians who chose to fight the war alongside American forces. When Boyko opens with a declaration like “Canada has always been a warrior state,” it’s clear he’s out to disabuse readers of some long-held pieties.

Notes on Grief, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Knopf, May)

“Grief is forcing new skins on me, scraping scales from my eyes.” Like so many who suffered loss this past year, Adichie heard her father’s final words on a Zoom call (he died suddenly, but not of COVID). In this slim, impactful memoir, which began its life as a New Yorker essay, Adichie reluctantly enters the grieving process, resenting and embracing its rituals, its universality and cruelly personal pain.

The Bomber Mafia: A Dream, A Temptation, and the Longest Night of the Second World War, Malcolm Gladwell (Little, Brown, April)

The indefatigable writer, podcaster and explorer of human foibles is back with an on-brand book about how a clash between good intentions and advanced military technology resulted in the deadliest night of the Second World War in the 1945 American firebombing of Tokyo.

The Hard Crowd, Rachel Kushner (Simon & Schuster, April)

This collection of two decades’ worth of the author’s non-fiction offers a wide-ranging mix of memoir, literary criticism and politics. Standouts include the opening essay about Kushner’s days racing, and crashing, motorcycles in California in the 1980s and ’90s and a behind-the-scenes look at some of the influences behind her bestselling novel The Flamethrowers.

Hawking Hawking: The Selling of a Scientific Celebrity, Charles Seife (Basic, April)

Seife’s sharp, irreverent biography posits the revered physicist as essentially a showman – a media creation sold to a public hungry for both inspirational narratives (“a being of pure intellect”) and for the salacious tidbits regularly coughed up about him in the tabloids (affairs, abuse, strip clubs). Among other withering allegations, Seife convincingly argues that Hawking’s books and “discoveries” following his celebrity- and fortune-making A Brief History of Time were, essentially, rehashes.

Women of the Pandemic: Stories from the Frontlines of COVID-19, Lauren McKeon (McClelland & Stewart, April)

COVID-19′s disproportionate impact on women is apparent in the numbers: In Canada, 81 per cent of health care workers are female, and twice as many women lost jobs during the pandemic as men, prompting some to call it a “she-cession.” In often wrenching portraits, McKeon brings us the women behind the statistics.

Nishga, Jordan Abel (McClelland & Stewart, May)

Using family archives, poetry, photographs, audio transcripts, social-media posts, affadavits and his own personal reminiscences, the Griffin Poetry Prize winner’s unique, and uniquely affecting, book is both a testament to and a grappling with “intergenerational trauma, Indigenous dispossession, and the afterlife of residential schools.”

Peyakow: Reclaiming Cree Dignity, Darrel J. McLeod (Douglas & McIntyre, March)

McLeod’s memoir – titled after the Cree word for “one who walks alone” – continues the story begun in the award-winning Mamaskatch. Over 30 years, we follow him as he makes the difficult decision to leave an elementary-school teaching job in Vancouver for a principal’s position on a northern B.C. reserve, and, later, serve on a delegation tasked with drafting the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Geneva.

Begin by Telling, Meg Remy (Book*Hug, April)

In lucid prose interspersed with illustration, quotations, white space and marginalia, American-born multidisciplinary artist and musician Meg Remy – best known for her Toronto-based experimental pop band, U.S. Girls, once dubbed “the greatest band working in North America today”– gives a compellingly non-linear account of a life touched by creative success, but also by public and private trauma.

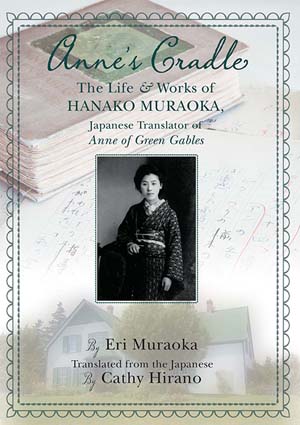

Anne’s Cradle: The Life & Works of Hanako Muraoka, Japanese Translator of Anne of Green Gables, Eri Muraoka (Nimbus, May)

Born to a conservative, impoverished Christian family, Hanako Muraoka is still revered in Japan for her translation of L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, a passion project undertaken at the height of the Second World War as bombs rained down around her. A bestseller in Japan when it was originally published in 2008, this biography by Muraoka’s niece has now been translated into English for the first time.

Picture books

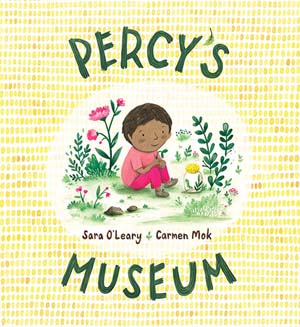

Percy’s Museum, Sara O’Leary; Carmen Mok, Ill. (Groundwood, April)

O’Leary’s book is nicely timed for the many kids who, like the titular Percy, moved from city to country this past year. At first, all Percy feels is loss and boredom, but as he slowly becomes attuned to nature’s rhythms, he finds new, better ways to entertain himself and, even more importantly, that “you can be alone without being lonely.”

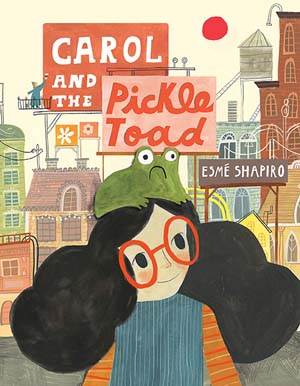

Carol and the Pickle Toad, Esmé Shapiro (Tundra, May)

In Shapiro’s silly but wise tale, a hat that’s actually a rude, overbearing toad stands in for those “friends” we stick with even though they make us feel terrible about ourselves. It’s only after young Carol divests herself of her less-than-fascinating fascinator – who unkindly critiques her artwork and makes demands in restaurants – that Carol learns to trust her own thoughts and opinions.

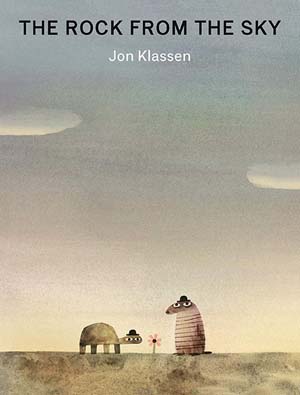

The Rock from the Sky, Jon Klassen (Candlewick, April)

The spirit of P.D. Eastman presides over Klassen’s newest, involving the fluctuating dynamics between a trio of behatted characters: a turtle, snake and a kind of racoon-possum hybrid. In three vignettes played out against a largely blank landscape, the companions must process the sudden appearance of the titular rock and, more ominously, a one-eyed, plant-obliterating alien.

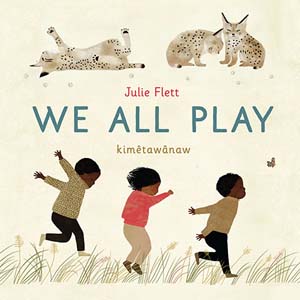

We All Play, Julie Flett (Greystone Kids, May)

In Flett’s charming, pared-down picture book, human children mimic the actions of their animal counterparts who “rustle / and roost” (bats); “nudge / and nuzzle” (bobcats); “bubble / and bend” (seals). In the end, sleep proves the one true common denominator. Includes a glossary of animal names in English and Cree.

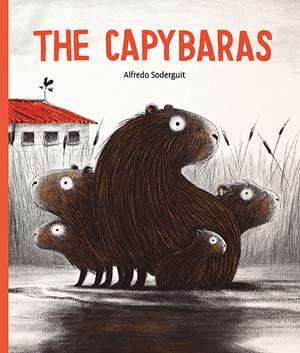

The Capybaras, Alfredo Soderguit (Greystone Kids, April)

In this charming tale about a clash of cultures, a flock of chickens find their mundane existence shockingly disrupted by a family of capybaras whose size and hirsuteness are immediately deemed outside the bounds of acceptability. The needed breakthrough comes – as it always does – through a next-gen chick-pup connection.

Hare B&B, Bill Richardson; Bill Pechet, Ill. (Running the Goat, April)

All is going swimmingly at the hare septuplets’ B&B until a suspicious looking “rabbit” shows up (among several red flags, her breath smells like meat and she watches “fox news”). Ultimately, however, it’s the hares who prove wilier than this coyote-in-lousy-disguise. Richardson’s witty wordplay might be the hook here, but readers will want to stick around for the satisfying molasses-and-feathering.

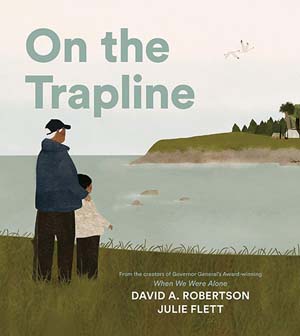

On the Trapline, David A. Robertson; Julie Flett, Ill. (Tundra, May)

This second collaboration between the Governor-General’s Award-winning writer-illustrator team – who share common Cree ancestry – focuses on the connection between a boy and his moshom (grandpa) as they travel by plane, foot and boat to the northern wilderness, where a young moshom once lived off the land with his family.

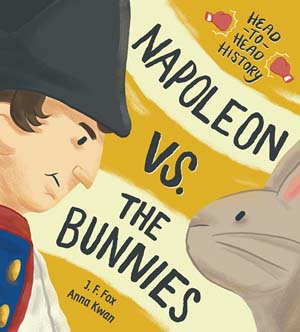

Napoleon vs. The Bunnies, J. F. Fox; Anna Kwan, Ill. (Kids Can Press, May)

Napoleon’s most famous defeat was at Waterloo, but his most ignominious, as this “head-to-head history” hilariously explains, happened a few years earlier, at a rabbit “hunt” meant to celebrate the signing of a peace treaty with Russia. As legend has it, instead of fleeing, the farm-raised rabbits turned the tables, swarming Napoleon and his entourage, who fled to their carriages.

YA & middle grade

My Body in Pieces, Marie-Noëlle Hébert (Groundwood, April)

Marie-Noëlle Hébert’s moodily cinematic black-and-white illustrations lend this emotional and often wordless graphic memoir tracing the author’s battle with body image a raw vividness, as we follow her from her tweens through to her 20s.

Amber & Clay, Laura Amy Schlitz; Julia Iredale Ill. (Candlewick, March)

Combining verse, prose and illustration, the Newbery Medal-winning Schlitz gives us a sui generis novel that hits the sweet spot for history, mythology and fantasy geeks. Set in ancient Greece, it follows Rhaskos, a Thracian slave boy, and Melisto, a spoiled girl from an aristocratic family – spiritual twins who never actually meet in the flesh.

Green Glass Ghosts, Rae Spoon; Gem Hall Ill. (Arsenal Pulp, May)

When the 19-year-old unnamed narrator of this coming-of-age novel by non-binary writer-musician Spoon first lands, guitar in hand, in Vancouver’s queer community after fleeing an abusive family situation in Calgary, it feels like a homecoming. But new problems soon replace old ones as Spoon’s hero negotiates toxic relationships, substance abuse and ghosts from their past.

Tremendous Things, Susin Nielsen (Penguin Teen, May)

Laced-through with the Governor-General’s Award-winning author’s trademark humour, Nielsen’s latest centres on geeky 14-year-old Wilbur Alberto Nunez-Knopf, a straight boy from a blue-collar, two-mother home who, in the hopes of impressing an attractive French exchange student and overcoming a life-defining middle-school humiliation, lets his gay pals and an elderly neighbour give him a Queer Eye-style makeover.

The Life and Deaths of Frankie D, Colleen Nelson (Dundurn, April)

Discovered starving in an alley when she was 10, teenaged Frankie, now fostered, knows nothing about her origins. Eerily familiar dreams about a 1920s carnival sideshow featuring a performer called Alligator Girl and a man named Monsieur Duval suggest a clue – especially after Frankie has an uncanny encounter with the latter in the flesh. Egyptian curses round out a fantastical scenario.

Misfit in Love, S. K. Ali (Simon & Schuster Kids, May)

In her award-winning debut, Saints and Misfits, Toronto’s S K Ali showed a flair for creating three-dimensional characters. In this breezy follow-up, teen Muslim heroine and titular misfit Janna Yusuf returns as she negotiates competing family agendas and her own tangle of crushes while helping to plan her brother’s wedding.

Tell Me When You Feel Something, Vicki Grant (Penguin Teen, June)

In this twist-filled #MeToo thriller, told through multiple and sometimes competing viewpoints, teenaged Viv signs up to be a simulated patient in an after-school medical-school experiment and, shortly afterward, ends up in a coma. Cellphone footage from a party suggests a potential overdose, even though Viv and her friends attest that she doesn’t drink or take drugs.

Sisters of the Snake, Sarena & Sasha Nanua (Harper Teen, June)

Hidden temples, dark magic and, yes, snakes feature in this role-switching story set in ancient India about identical twins Rani and Ria – a princess and a street urchin – who, after discovering each other’s existence, join forces to stop a war. Twins themselves, first-time Mississauga-based authors Sarena and Sasha Nanua bring rare insider insights to their characters.