Taxes, lamb and the heady scent of cherry blossoms – all indubitable signs that spring is finally here, and with it a new crop of books covering everything from plants to propaganda; grieving to grievance; and Jean de Brébeuf to Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Books we're reading and loving this week: Globe staff and readers share their picks

Many of the season’s bigger titles (among them books by Colm Toibin, Claire Messud, Salman Rushdie, Michael Ondaatje, Wade Davis, Russell Banks and Lydia Millet) were covered in our Most Anticipated feature back in December. In the interest of variety – and not repeating ourselves – those do not appear in the list of 30 promising below, but can be seen here.

MARCH

A Darker Shade of Blue: A Police Officer’s Memoir, Keith Merith (ECW) Merith humbly recounts the trials, tribulations and successes he experienced during the 30 years in which he rose (too slowly at times) through the ranks of the York Regional Police force. His 2017 retirement – as superintendent – turned him ruminative, and he lays out why racism still matters inside and outside the force. “The issue of police brutality, which has largely targeted Black lives,” Merith writes, “has lit a fire in me.”

Dispersals: On Plants, Borders, and Belonging, Jessica J. Lee (Hamish Hamilton) At times reminiscent of Kyo Maclear’s luminous Unearthing, and inspired by her peripatetic life and mixed Taiwanese-Welsh ancestry, the Canadian historian harnesses memoir and ecology in a series of thoughtful essays looking at the intertwining between humans and plants, including, as they migrate, their many shared labels: native, invader, alien and colonist.

Glorious Exploits, Ferdia Lennon (Henry Holt) “Let’s put on a show!” takes on a darkly funny meaning in this debut novel, set circa 400 BC, about two male friends – one a hardcore Euripides fan – who concoct the brilliant idea of staging Medea in a local quarry using defeated, starved Athenian prisoners as their cast (according to Thucydides, it’s been done). Outlandishly anachronistic Irish-inflected dialogue (the author is from Dublin) proves a deep comedic well.

How to Win an Information War: The Propagandist Who Outwitted Hitler, Peter Pomerantsev (Public Affairs) Pomerantsev, who’s written extensively about disinformation in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, turns his focus to a master propagandist of yesteryear. Sefton Delmer, a German-speaking Australian, countered Hitler’s influential radio broadcasts during the Second World War with a series of his own, delivered by the foul-mouthed, army-loving, uber-patriotic (and entirely fictional) Der Chef, who sowed skepticism about the Nazis by portraying them as a bunch of louche Bolsheviks. (In a satisfying bit of circularity, Pomerantsev made use of Delmer’s techniques when Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky employed him as an adviser during the writing of this book.)

Nowhere, Exactly: On Identity and Belonging, M. G. Vassanji (Doubleday) “Mixed and democratically idealistic on the surface, segregated at its heart” is how the two-time Giller winner characterizes the Canada he immigrated to in 1980, from Tanzania. The country’s diversification – mostly positive – has also meant people, especially artists and writers, are increasingly labelled according to their ethnicity or ancestry. As someone whose mixed background has often left him feeling betwixt and between, Vassanji here offers a “series of meditations” on what it means to belong.

Shepherd’s Sight: A Farming Life, Barbara McLean (ECW) McLean became a sheep farmer in Ontario’s Grey County in the early seventies, in part as an escape from the political unrest of that time, but also as an act of defiance against her urban, bourgeois upbringing. Fifty years later, she reflects on what it is to live a life tied to the rhythms of nature, a rhythm now increasingly drawing her, a woman in her 70s, into its inevitable end game: “I fear losing my sense of self if I can no longer shepherd my sheep.”

The Ancient Art of Thinking For Yourself: The Power of Rhetoric in Polarized Times, Robin Reames (Basic) Learning the art of rhetoric – the basis of Western education for two millennia – helped Reames, an English professor, get the upper hand in arguments with her father during her Bible Belt upbringing. Here, in funny, lively prose that draws on ancient and modern-day examples, she teaches readers how to avoid becoming victims of manipulation – political and otherwise – by harnessing language’s powers of persuasion.

The Blues Brothers: An Epic Friendship, the Rise of Improv, and the Making of an American Film Classic, Daniel de Visé (Grove) De Visé's book offers a completist’s account of the genesis of Aykroyd and Belushi’s act and the drug-fuelled comedy world and culture out of which it emerged. It’s also the most detailed biography yet of the pair’s quieter, brainier, Canadian half, Aykroyd, who in interviews discussed his Catholic Ottawa upbringing and first exposure to the blues at Montreal’s Expo 67, where he managed to catch Memphis soul duo Sam & Dave.

APRIL

Clear, Carys Davies (Scribner) The Welsh writer’s fiction has often gravitated to wild, inaccessible landscapes, and her third novel is no exception. During the traumatic Scottish Clearances of the mid-19th century, a Presbyterian minister, newly unemployed, is dropped off at a remote island in the North Sea with instructions to expell its sole resident, but ends up forming a deep connection with the latter following a near-fatal accident.

Curiosities, Anne Fleming (Knopf) Fleming’s historical novel uses the frame device of a researcher who stumbles upon a series of 17th-century manuscripts with clashing accounts of events that took place in and around the lives of two girls, Joan and Thomasina, who first meet as child survivors of the Plague that hits their English village, then later reunite as adult lovers, Thomasina having transformed into the cross-dressing Tom.

Fi, Alexandra Fuller (Grove) Fuller’s four previous memoirs, which detailed her African upbringing, contained a fair share of personal tragedy, but nothing like this fifth one – which is garnering lots of early praise – about the sudden death, in his sleep, of her 21-year-old son, Fi: “His life flashed in front of my eyes in fragments, then. It was like photographs and scraps of memorabilia falling out of a keepsake chest; my life, too.”

Muse of Fire: World War I as Seen Through the Lives of the Soldier Poets, Michael Korda (WW Norton) Six portraits of major First World War soldier-poets – Rupert Brooke, Alan Seeger, Isaac Rosenberg, Robert Graves, Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen – by the long-time Simon & Schuster editor-in-chief and historian, now 90, are a worthy companion to Paul Fussell’s 1975 The Great War and Modern Memory, and a fresh reminder of the horrors of the war that didn’t end all wars. Far from it.

The Age of Grievance, Frank Bruni (Simon & Schuster) Probing the rise of what some have called the “grievance industrial complex” – whose denizens straddle the political spectrum, and include establishment entities such as Fox News, the Sussexes and even the United States Supreme Court – the veteran New York Times columnist makes of this book an exasperated, and often funny, plea for us all to quit the kvetching and revelling in victimhood and get on with it already.

The Hollow Beast, Christophe Bernard (Biblioasis) The seed of Bernard’s big, high-octane novel, which won several Quebec prizes, and was a finalist for the 2018 Governor-General’s Award in French, is a 1911 hockey game in Quebec’s Gaspé Peninsula whose bizarre, controversial ending results in a generations-long vendetta. Thomas Pynchon meets Rabelais and Don Quixote meets Who Framed Roger Rabbit are two of several crossbreed critical comparisons the book has inspired.

The Peace, Roméo Dallaire (Random House) The Canadian general has now written five books stemming from the “biblical horror” he experienced as a UN peacekeeper during the 1994 Rwandan genocide, which cover topics such as the use of child soldiers, his struggles with PTSD and his advocacy work to prevent mass atrocities. In this timely new one, Dallaire turns to Dante as he lays out a practical blueprint for “true and lasting” world peace.

So Long Sad Love, Mirion Malle (Drawn & Quarterly) The France-born illustrator’s debut graphic novel, This is How I Disappear, about millennials coping with mental-health issues – was nominated for several prestigious awards. Her sophomore effort is an Agnès Varda-influenced tale – rendered in fine lines and a warm, subtle palette – about a young woman navigating the minefield of love and relationships in contemporary Montreal, where Malle now lives.

The Spoiled Heart, Sunjeev Sahota (Viking) As in novels such as China Room and The Year of the Runaways (both of them Booker nominees), Sahota continues to focus on South Asian immigrant lives in contemporary Britain. This time, a man’s past and present collide uncomfortably when, during a tense battle to become the first racialized person to head his labour union, he encounters a woman who may be connected to the central trauma of his life: the fire that killed his mother and young son.

Traitor By Default: The Trials of Kanao Inouye, the Kamloops Kid, Patrick Brode (Dundurn) Brode’s stated aim is to dispel the many myths surrounding the bizarre story of the second Canadian, after Louis Riel, to be executed for high treason. The son of a Canadian hero born in 1916 in B.C., Inouye moved to his ancestral homeland, Japan, during the Second World War, becoming notorious for his sadistic way of dealing with Canadian survivors of the Battle of Hong Kong.

The Wide Wide Sea: Imperial Ambition, First Contact and the Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook, Hampton Sides (Doubleday) Cook has been dubbed “the Columbus of the Pacific,” despite the fact that he was not, like the latter, a conqueror or a colonizer (in 2021, Cook suffered a familiar modern ignominy when his statue in Victoria got toppled by protesters). The author, an American historian, here lays out the map maker’s complex legacy through the prism of his wildest, and final, journey, which began in 1776 and took him to Tasmania, Tahiti and Alaska, among other places.

MAY

Bird Suit, Sydney Hegele (Invisible Publishing) Hegele’s first novel (after their story collection, The Pump, which was shortlisted for the Trillium Award), weaves a gothic folktale around Georgia Jackson, the daughter of a female taxidermist who broke with local custom in their small peach-based tourist town by raising Georgia herself – instead of allowing the local cliff-dwelling sirens (who usually take on the babies of teenaged mothers) to do so at the bottom of the town’s lake.

Crosses in the Sky: Jean de Brébeuf and the Destruction of Huronia, Mark Bourrie (Biblioasis) Bourrie’s latest, like its Charles Taylor Prize-winning predecessor, Bush Runner, focuses on the clash between European and Indigenous cultures in 17th-century colonial North America. Here, it’s the events leading to the violent ruin of Huronia, traditional home of the Huron-Wendat people, as they were experienced by the French Jesuit missionary and mystic Jean de Brébeuf, co-founder of Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons near present-day Midland.

Disembark, Jen Currin (Anansi) In their second collection of short stories, the American-Canadian poet explores relationships between urban queer folk in their many iterations: platonic, romantic or full-on carnal.

How It Works Out, Myriam Lacroix (Doubleday) Each chapter of this surrealistic first novel by the Vancouver-based Montrealer – which bagged a hyperbolic blurb from George Saunders (“audacious, breathtaking and inspiring”) – offers up entirely different versions of its protagonists, a lesbian couple named Myriam and Allison. (To wit, in one, they’re dogs.)

In My Time of Dying: How I Came Face to Face with the Idea of an Afterlife, Sebastian Junger (HarperCollins) Junger had survived a near drowning, and war reporting in Afghanistan, when an undiagnosed aneurysm ruptured and almost killed him while he was standing in his driveway during the pandemic. A subsequent near-death experience, in which he came face-to-face with his dead father – a scientist “who didn’t believe in anything that he couldn’t measure and test” – prompted this slim but deeply searching book.

The Internet of Animals: Discovering the Collective Intelligence of Life on Earth, Martin Wikelski (Greystone) Not to be confused with the nefarious “internet of things” – where your air fryer shares your health data with your insurance company – an “internet of animals” is Wikelski’s ambitious project, in collaboration with NASA, to track global migration patterns by satellite with the aim of protecting animals and their habitats. In detailing that, and a host of other fascinating studies he’s done involving everything from rats to ocelots to storks, Wikelski adds to the compelling picture of animal intelligence presented in recent books such as Ed Yong’s An Immense World.

The Cleopatras: The Forgotten Queens of Egypt, Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (Basic) You knew there were multiple Napoleon Bonapartes, didn’t you? But what about Cleopatras? Turns out the Egyptian queen you’re thinking of (the one played by a kohl-eyed Elizabeth Taylor) was – according to the Welsh historian-author of this highly readable multibiography – actually Cleopatra VII: the last, and best known in a line of seven “capable and imposing Cleopatras who wielded absolute power and courted unrivalled authority.”

The Damascus Events: The 1860 Massacre and the Making of the Modern Middle East, Eugene Rogan (Basic) The Oxford historian’s book about one of the most consequential events in the history of the Middle East – the brutal eight-day massacre of Christians in Syria in July, 1860 – wouldn’t have been possible had he not fortuitously stumbled upon an eyewitness account of the events by Mikhail Mishaqa, the first American vice-consul to Damascus, and one of the most compelling intellectuals of his day, on the wrong shelf of the U.S. National Archives in Washington, back in 1989.

The Devil’s Best Trick, Randall Sullivan (Grove) Self-classified as “part true-crime story, part religious and literary history,” this book is a world-scouring investigation into the nature of evil from biblical times through the witch hunts of the 17th century and the Satanic panic of the eighties, as well as evil’s depiction in literature. Sullivan often injects himself into the mix, describing his unnerving experiences attending a Black Mass ceremony in Mexico and an exorcism in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth, Zoe Schlanger (HarperCollins) Books about the plant kingdom are having a moment these days. Witness the success of titles by Michael Pollan, Peter Wohlleben, Suzanne Simard, Diana Beresford-Kroeger and Robin Wall Kimmerer, who calls this one (its gist right there in the subtitle) by a Montreal- and Brooklyn-based Atlantic staff reporter, “a masterpiece.”

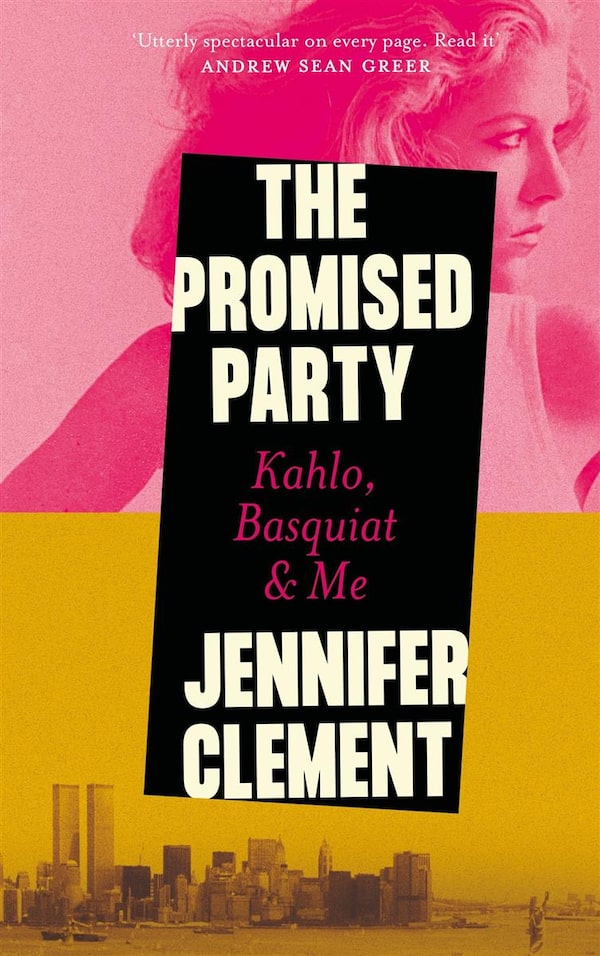

The Promised Party: Kahlo, Basquiat and Me, Jennifer Clement (Canongate) Novelist Clement’s (A True Story Based on Lies) coming of age in the 1960s through to the 80s, took place amidst a who’s who of the art world. In Mexico City, where she lived as a child, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’s Studio House was her second home, and Diego’s granddaughter Ruth her first friend. In New York, she hung with Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and William Burroughs. She brings that rarefied world to life here, in characteristic episodic, poetic, yet unshowy prose.