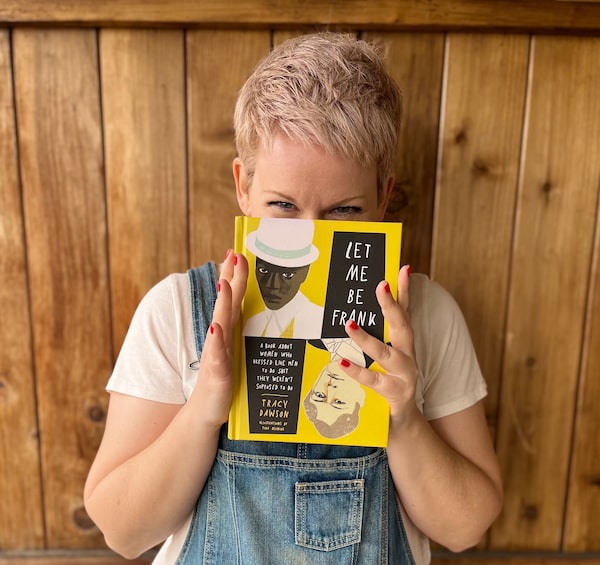

Author and comedy writer Tracy Dawson.Kathleen Munroe/Handout

The actor and screenwriter Tracy Dawson was meeting with TV executives about a writing gig when one of them told her the shows she was interested in didn’t have any “female needs” in terms of writing staff. Dawson, who started her career at Second City and whose acting credits include a Gemini for her role on the TV show Call Me Fitz, left the meeting in shock. “I’d never even considered that as a possibility,” says Dawson, who was born in Ottawa and now lives in Los Angeles. “I was like, I’m a great comedy writer. I write great jokes. That’s what I do, and that’s how people will see me. So I felt stupid, in a way, because I didn’t see it coming – that I would be considered a ‘woman writer,’ not a comedy writer.”

Dawson briefly contemplated what posing as a man could do for her career, then decided to take that idea and write about it, first in a couple of TV pitches and then as a book. Let Me Be Frank: A Book About Women Who Dressed Like Men To Do Shit They Weren’t Supposed To Do was released on May 10. Dawson spoke to The Globe and Mail’s Jana G. Pruden about defiant women, the lessons of history and finding hope at the present moment.

How did you find and decide on the women to write about?

I love sitting at the computer for hours and researching. I just love it. I really became good friends with Google, and I dug and I dug and I dug. There are so many people who were left out of the history books. We all know who was in charge of documenting stuff, so we know what they deemed important to write down and what they didn’t. There are stories out there we’re never going to know, because they were about Black people, women, queer people, people who were great and did incredible things – it just wasn’t documented. And that’s maddening.

This has been a really … let’s say interesting week to read your book, given the news coming out of the U.S. about Roe vs. Wade. On one hand, I found it inspiring to think about how women have resisted and persevered throughout history, but also really infuriating to confront how much is still stacked against women. How have you been feeling?

It’s remarkable this is happening as the book is about to launch. At first, I just felt sick and paralyzed and like I couldn’t breathe. So many people were tweeting about how even if all the signs were there, even if we knew this was coming, it doesn’t change how this feels in your body. In your body. It’s hard for me to talk about because I get so worked up. It’s crazy making. It actually makes you crazy.

That’s one word for it. Is there anything you learned in the process of this book that makes you feel hopeful about where we could go from here?

It’s a hard week for hope. I saw someone tweet, “Despair is very appealing at times.” But the hope is that I believe in women as extraordinary and persevering and persistent beings, and I know I’m going to get fuelled and inspired by other people, and that I don’t have to do this or feel this or fight this alone. That gives me hope.

I would love to talk about the voice and writing style a bit. This is really serious history, but you’ve written it in a way that’s so engaging. It has this modern and direct voice, and it’s fun and funny. Can you talk a bit about the decision to take on these important lives and the legacy of these women with this kind of voice and style?

I knew I wanted this book to be in my voice. And my voice is someone sitting across from you in a booth at the diner. I wanted to grab the reader’s hands and say, “You’re not gonna believe this.” I wanted them to feel my excitement and passion. I wear my emotions on my sleeve. I wanted to make people laugh, but I’m also not hiding my anger, my incredulousness. I don’t think I use humour to tone down hard messages. I think I do it in a way that almost amplifies the messed-up nature of being alive as a human woman.

You wrote about Jezebel writer Catherine Nichols sending out her book under a male name and the more positive responses she got. In the introduction to your book, you said you didn’t seriously consider transforming into the male version of yourself to write on a TV show. But did you think about it?

Yeah, absolutely. I’m a hustler. I want the gig. I want a chance to work, and I’m pretty into myself. I think I’m good, right? I thought about it, but I didn’t think about it. Also, living a lie – that would just be so stressful. My anxiety would probably be through the roof. Then I was like, well, what’s the realistic response to this? It’s just to keep going – take the next meeting and hope the executive doesn’t think that way or the showrunner doesn’t just see you as a woman writer. And just keep writing kick-ass scripts that people can’t deny.

That’s why people of colour and women and queer people always have to be amazing. They have to be the best. A female filmmaker can’t make a kind-of-okay movie. If she makes an okay movie the way most first-time male directors make, she’s not going to get a second movie.

Not all your subjects are heroes. Like, the “witch-pricker” Christian Caddell was really not a great lady, all things considered. Catalina de Erauso is another one who stood out. Was it different when you were writing about a woman who was more problematic?

It was different, but at the same time, I’m coming from this world where I’ve written a fair amount of anti-heroines and had a hard time selling them, when anti-heroes like a Breaking Bad-type character was all the rage, or the Tony Soprano. Executive producers would say, “We love the idea of an anti-heroine.” So I’d bring them a great script that everyone agreed is really funny and dark and great, and they’d be like, “Ohhhh, that’s a bit too dark for a woman.” You say you want the anti-heroine, but then you don’t green-light the shows, and you’re still monitoring and judging and deciding. You’re gatekeeping. Bad, but not that bad.

One thing you can say about Caddell and de Erauso is they chose for themselves. They didn’t answer to other people. If anti-hero characters have a right to exist and have stories written about them and be out there in the world, and people can love them, hate them, be obsessed with them, then why not women? Why not?

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.

Jana G. Pruden

Jana G. Pruden