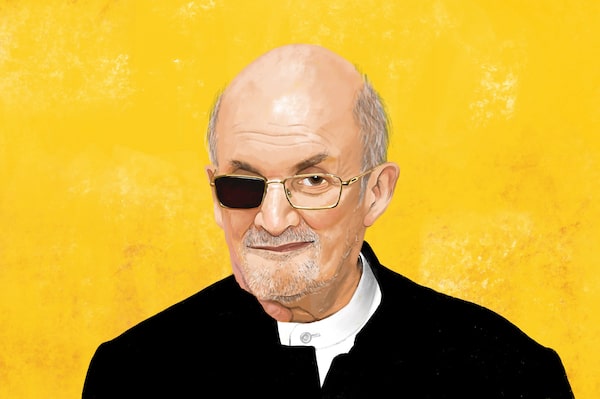

Salman Rushdie’s new memoir, Knife, is about the attack that nearly cost him his life.Illustration by Stef Wong

In Knife, Salman Rushdie’s new memoir about the attack that nearly cost him his life, he describes two thoughts that came in the moment before the stabbing: “So it’s you” and “why now?”

Since Ruhollah Khomeini, Iran’s late theocratic leader, issued a fatwa calling for Rushdie’s death over his depictions of the prophet Mohammed in the 1988 novel The Satanic Verses, the writer had been prepared for this to happen. But when it did, he couldn’t believe it had taken so long.

Rushdie was about to start a talk at the Chautauqua Institution’s open-air amphitheatre in upstate New York when, from the corner of his right eye, he caught sight of a black-clad man rushing the stage. Over the course of 27 seconds that morning of Aug. 12, 2022, the assailant would stab the novelist a dozen times before being wrestled off.

“I knew he wasn’t coming up to shake my hand. It was a flashback to many, many years earlier,” he tells me. In the first decade of the fatwa, Rushdie, then living in London, had gone into hiding with around-the-clock protection from Scotland Yard. “I had to consider the possibility that somebody was going to attack me. I thought about how there might be a moment when someone jumps out of a crowd.”

After moving to New York in 2000, he decided to live openly. No police or guards. Solo travel. Hundreds of public appearances without a whiff of trouble. “I had actually stopped thinking about the person jumping out of the crowd. And then he jumped out of the crowd,” he says.

Book recommendations from Globe staff and readers

In the initial seconds of the attack, Rushdie thought the man had only punched him. “Then, there was blood spilling all the way down my shirt, I realized that he’d actually had a knife,” he says. “I never saw the knife. I couldn’t tell you what the knife was like. I felt it.”

Today, as he sits on a warm spring morning in the Midtown Manhattan offices of Andrew Wylie, his long-time literary agent, the physical marks of the assassination attempt are apparent. Blinded in his right eye, Rushdie wears spectacles with one blacked-out lens. His right cheek has a long scar. His left hand, whose tendons were all severed, is still stiff. Under a checked blue sport coat, he is noticeably thinner.

Over the course of an hour-long conversation, however, the 76-year-old’s famously lively personality is undimmed. He cracks jokes. He tells anecdotes. He details everything from his writing process to his views on an increasingly dangerous world.

Rushdie's new book "Knife" is pictured in a bookstore in Los Angeles, California on April 15, 2024.GILLES CLARENNE/Getty Images

While Knife is a straightforward, mostly linear 209-page memoir – a stark departure from Rushdie’s multilayered novels – he says it was nonetheless a struggle to write at the beginning. He rose from his desk at the end of many workdays, he recalls, having completed just six sentences. Then, once he had finished recounting the stabbing itself, his speed suddenly picked up.

“Actually reliving the attack and describing it in detail, that first chapter, was really, really hard to write. Once I got through that, it started accelerating. And the second half of the book came quite fluidly,” he says.

Key to the book was also figuring out its structure. Simply describing the attack and his recovery, he says, would not have been substantial enough to build a memoir around. So he decided to also tell the story of his relationship with his wife, the poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths, whom he married in 2021.

“There were two forces at play: one of hatred and one of love, embodied in the characters of the attacker and of Eliza. I was the third point of the triangle,” he says.

In its pages, Rushdie comes across as unafraid to be vulnerable. He describes in detail not only the stabbing and his injuries but every one of his subsequent medical procedures. There are tender passages about his marriage with Griffiths, his fifth, and his relationships with his two grown sons.

His usual sense of humour is also in evidence. On the night he met his wife, he recounts, he walked into a plate-glass door and fell on his back. She escorted him home and they sat up talking until 4 a.m.

When asked if it was hard for him to reveal so much, he says he had no choice if he wanted to do the story justice. He recalls a time when Doris Lessing, the late, long-lived British novelist, was mulling writing a memoir and asked for his advice. Her dilemma, he says, was that she “had affairs with a lot of important people” and wasn’t sure if she could put them in. He told her that, if she couldn’t be completely open in the book, she shouldn’t write it.

“She said, ‘Well, I think volume one will be okay because they’re all dead, but volume two might be a problem,’” Rushdie chuckles. “Anybody who faces the subject of telling the truth about their life has to face the fact that they’re going to expose themself, they’re going to make themself vulnerable and naked in a public place.”

Rushdie, pictured here in New York, says he contemplated meeting with his attacker in jail but ultimately decided against it.Andres Kudacki/The Associated Press

Throughout Knife, Rushdie avoids using his assailant’s name, referring to him instead as “the A.” The suspect, Hadi Matar, is a New Jersey man who was 24 years old at the time of the stabbing. He told the New York Post in a jailhouse interview that he had read just two pages of Rushdie’s writing but had watched YouTube videos of his lectures. He decided to take him out because the author had “attacked Islam.”

At one point, Rushdie says, he mulled trying to meet with Matar, who is in jail awaiting trial. Griffiths was against the idea and he ultimately agreed. “I’m not sure I’d get very much of value beyond a series of ideological clichés.”

So instead, Rushdie decided to write a chapter imagining a conversation between himself and his attacker in which they explore the man’s motivations and religious beliefs. Reading it reminded me of a central episode in The Satanic Verses: One of the novel’s characters dreams that he is the archangel Gabriel appearing to a Mohammed-like figure to reveal the Quran. The revelations, however, seem to be coming from within the prophet and are merely repeated back to him by his celestial interlocutor.

Rushdie says the parallel was inadvertent.

“Now that you remind me, I think, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s true what you say.’ But I wasn’t thinking of it. I was thinking more about Socratic dialogues,” he says. What perplexed him was how a man with no previous criminal record could decide to commit such an attack based on so little. If he had pitched such a character in a novel, Rushdie says, his editors would have told him, “Not convincing; not enough motivation.”

Another striking passage in the book describes a recurring dream of Rushdie’s: He is rolling on the floor of an ancient Roman amphitheatre, trying to dodge a gladiator’s stabbing spear. The vision came to him two nights before he went to Chautauqua and he told Griffiths that he didn’t want to go. He ultimately decided that, with tickets bought and a paycheque on the line, he had to make the trip.

Not that Rushdie wants anyone to get the impression that this was a heavenly warning. While his family background is Muslim, he is an atheist. In Knife, he is explicit that he had no godly revelations during his near-death experience. “There was nothing supernatural about it. No ‘tunnel of light.’ No feeling of rising out of my body.”

Rushdie’s work has always been inextricably intertwined with geopolitics. Midnight’s Children deals with the struggles of Indian independence. The Satanic Verses opens with a terrorist attack patterned after the 1985 Air India bombing and grapples with deadly xenophobia in the United Kingdom. The Moor’s Last Sigh features Hindu-Muslim religious violence.

In Knife, Rushdie laments rising “bigoted revisionism” in both the U.S. – MAGA, book censorship, abortion bans – and his native India, connecting them thematically to his own fight against extremists bent on silencing him.

The day we meet, Donald Trump is a 25-minute subway ride away, sitting in a Manhattan courtroom at his criminal hush-money trial.

“The great talent of Donald Trump has been getting away with it. Long before he was in politics, he’s been getting away with it all his life: scamming people working for him, not paying his bills,” Rushdie says. “I have a fantasy of the orange jumpsuit and the perp walk. I think that would be a good look for him.”

Rushdie and the future president actually crossed paths a few times in the early 2000s, he says. One was at a Crosby, Stills and Nash concert, where the writer recalls being surprised to see the bouffanted billionaire on his feet singing along to Woodstock. Another was at a charity event during the U.S. Open Tennis Championships, when Trump offered Rushdie the use of his private box (Rushdie declined.)

A third was at the Metropolitan Opera, when Trump walked by with an entourage. “He snapped his fingers and he went, ‘Rushdie, you’re the man,’ and I thought, ‘I know the answer to this,’” the author recounts. “I said, ‘No, Donald, you’re the man.’ He was really happy.”

Across the country, hundreds of Rushdie’s fellow authors have found themselves up against the impulse to suppress books that he has already spent decades combatting. Conservative U.S. school boards and city councils in recent years have barred everything from Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale to Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer from libraries.

The new censorship, Rushdie says, is “almost entirely white pressure to ban books which speak openly about race in America. When it isn’t about race, it’s about gender. Conservative America wants to live in the 19th century, maybe earlier – when there were slaves.”

He is also concerned about what he sees as a rising tendency on the young political left to declare some topics off-limits to discussion for fear of offending disadvantaged groups. “There is pressure from progressive voices saying, ‘You mustn’t upset people.’ If that’s the rule, then nothing can be said. Because everything that anybody says will upset somebody,” he says.

India, meanwhile, is in the midst of an election in which Prime Minister Narendra Modi could secure a third consecutive majority. Over his decade in office, he has worked to disenfranchise Muslim voters, disqualified opposition candidates from running and used an anti-terrorism law to silence critics.

“There’s a lot of anti-democratic stuff going on,” Rushdie says. “The rhetoric of Hindu nationalism has managed to persuade a very substantial percentage of Indian Hindus that the country should no longer be a secular state. The word ‘secular’ is in the constitution of India and it’s clearly the plan of this administration to reverse that. If it does, that opens the gates for another round of sectarian violence.”

On Israel’s war with Hamas, Rushdie expresses outrage over both the terrorist attack and Israel’s subsequent killing of Palestinian civilians.

“The October 7th attack was disgusting and I somewhat worry about the ease with which it’s been swept aside by people wishing to protest Israel’s behaviour in Gaza,” he says. “My loathing for Hamas is only matched, perhaps, by my loathing for Benjamin Netanyahu. What is happening in Gaza, the mass murder, is also disgusting.”

He isn’t sure what the solution is. Hamas’s heads “leading the high life in Qatar in 19-star hotels” profess to want perpetual conflict with Israel, he says, making the prospect of a ceasefire remote. Similarly, he doesn’t understand how Netanyahu imagines that bombing Gaza will destroy an organization whose leaders are 1,800 kilometres away.

“Where is the path of justice? That is what I ask myself, and I can’t really see that,” he says.

More than a year and a half after facing death, Rushdie says he’s in a good place. He had thought about the possibility that he would retraumatize himself by having to promote a book about the experience. As it turns out, writing about the stabbing has helped him compartmentalize.

“There’s some weird little psychological switch that got thrown in my head,” he says. “Instead of my talking about an attack against me, I’m talking about a book that I wrote about an attack against me. It feels like, ‘Well, here I am talking about a book. I’ve done that before.’ And so far, it feels okay.”

The only thing that gets Rushdie down these days is the notion that the world doesn’t appear to be improving. He describes himself as a child of the sixties: He was 21 during the revolutions that convulsed the West in 1968.

“With the civil rights movement, with the feminist movement, and sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, the world seemed to be getting better,” he says. “I’m kind of sad because I thought as a young person that we might be living at the beginning of an improvement in the world and then, boy, did that not happen.”

Asked if the attack has changed his approach to what he wants to achieve as a writer and whether it’s more urgent, now, to explore political themes in his work, Rushdie demurs. For one, after 22 books, he doesn’t know if he will write another.

Ironically, he says, he has long wanted to write a Jane Austen-inspired novel that deals purely with the personal lives of its characters, with no intrusion from the wider world. Austen’s works, he points out, were contemporaneous with the Napoleonic Wars, but with the exception of soldiers showing up in uniform to parties, don’t deal with Trafalgar or Waterloo.

“She could make a deep and full portrait of her characters without needing to refer to the public arena,” he says. “But we don’t live in that world any more. Now, the public arena impinges on private life so directly and constantly through our phone, through our television, it’s very hard to explain a life fully without taking into account the impact on that life of matters from outside.”

In Midnight’s Children, the narrator, Saleem Sinai, memorably advises the reader: “To understand me, you’ll have to swallow a world.” The same could be said of both the life and oeuvre of Sinai’s creator.

“I’ve always had a fantasy about writing a novel about two people sitting under a tree by a riverside, drinking a glass of wine – and nothing else, just private life,” Rushdie says. “I’m going to be 77 any second and I haven’t succeeded yet.”