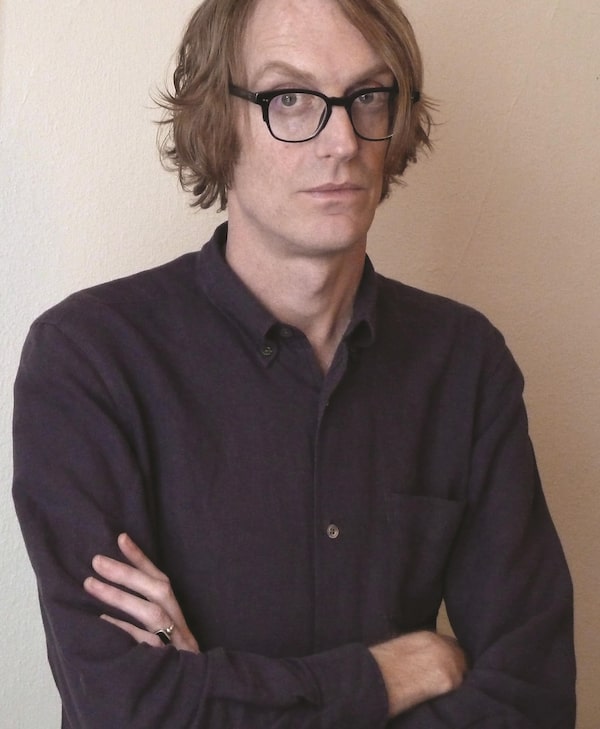

Author Patrick DeWitt.

Six years ago, after Patrick deWitt’s The Sisters Brothers was a smash hit, Brick Magazine published a short story by the author called The Looking-Ahead Artist. DeWitt told a tale of two shipwrecked English seamen who wash ashore on an island and encounter a thriving society. The time and place are not specified, but it feels like the 17th century in the South Pacific. This was the seed that was to become the final part in a loose trilogy of stories set in bygone eras.

The Sisters Brothers, published in 2011, was first: a comic and violent Western about two hit men in 1851 on the U.S. West Coast during the gold rush, followed by 2015′s Undermajordomo Minor, a sort of gothic fairy tale for adults, set in a dark castle looming over a village in Europe in the mid-19th century. For the third and final work, DeWitt was ready to set out into world of seafaring explorers. He had books about Columbus and Magellan. He had a list of archaic words. And then, nothing.

“I sat down to do it and I just didn’t want to do it. I wanted to write something that took place now,” deWitt, 43, said in an interview.

The result is French Exit, a story of a mother and her grown son, who lived a life of luxury in contemporary New York until they went broke. They set sail for Paris, where the story plays out. French Exit is unlike the previous work of the Vancouver Island-born and Portland, Ore.-based novelist, but it is stamped by his hallmarks: a dry comic touch, delightful and propulsive dialogue, and a dab of the fantastic.

“This book just sort of wanted to be breezy, chatty, not a particularly lengthy or dense book,” deWitt said. “It’s an easy book to read. I like that idea, I like the idea of writing user-friendly books.”

While this is not the third in the imagined trilogy, French Exit does feel like something of a cousin to The Sisters Brothers, where the back and forth between Eli and Charlie Sisters is what made that story so widely loved. In French Exit, the strange bond between 65-year-old Frances Price and 32-year-old Malcolm drive the story. But Frances and Malcolm are not Eli and Charlie. The pair have detached themselves from the world, whereas Charlie and Eli lived in the muck of it. DeWitt, however, is deft in his ability to spark at least some affection for unlikable characters, as he did with the murderous Sisters and again in French Exit for the Prices. It is the grey tones in his characters that fascinate deWitt.

“They’re not particularly admirable people,” he said of Frances and Malcolm. “These are not empathetic people. But I did come to care for them.”

What is best about French Exit is Frances Price, deWitt’s first lead female character. At the Parisian café Frances haunts, deWitt writes: “The staff called her Jackie O for her coldness, her inscrutability, her fashionable beauty.” When her son’s girlfriend meets her for the first time, deWitt describes Frances as having "a searching, malevolent flicker in her eye that marred her person and kept Susan at a remove.”

Frances, as a girl, grew up with a “demon” of a mother. As an adult, she married Franklin Price, who reveled in his lashing anger – a man propelled by the “tactile pulse of psychic violence” – and was an adulterous cad who made millions as a lawyer defending the indefensible. He died of a heart attack some two decades before the book begins, but haunts Frances still (as the spirit and mind of the man entombed in the body of a now-elderly cat, Small Frank, who adds a spice of weird to this ride).

Frances spent the intervening years since her husband’s death burning through the tainted fortune he left behind. The book opens near an end: “Frances’s concern was existential; she lately had found herself mired in an eerie feeling, as one standing with her back to the ocean,” deWitt writes. Most of all, Frances is lonely, another of the threads that bind deWitt’s work. Late on a Christmas Eve in the Paris apartment on Île Saint-Louis they’ve borrowed from a friend, Frances stands alone in the kitchen and smokes, “to feel her loneliness and to think of it.”

DeWitt said the theme is one that draws him back when he sits to write. “I don’t know anyone who isn’t at least somewhat lonely,” he said.

In French Exit, deWitt’s dialogue snaps, as always. It leavens the darker aspects of his stories. “It’s my greatest joy in writing,” deWitt said, “just having two people chat.”

In this, Frances and Malcolm are excellent foils. Malcolm is a sad sack. His mother, once esteemed, has her ills, too. Together, they have each other, forming a peculiar duo. In a memorable exchange, on the ship to France after a night of drinking, Frances asks her son about his relationship with a young woman onboard.

“So, you made love to her?”

“Well, yes.”

“Did you do a good job?”

“Not a very good one, no.”

“Do you normally do a good job?”

“Sometimes I do. I think the problem is that I don’t care enough.”

Frances said, “If you do one thing well, it might as well be that.”

As summer nears its end, French Exit is a fun read from a writer who ever-more establishes himself as one of this country’s most distinct voices in fiction.