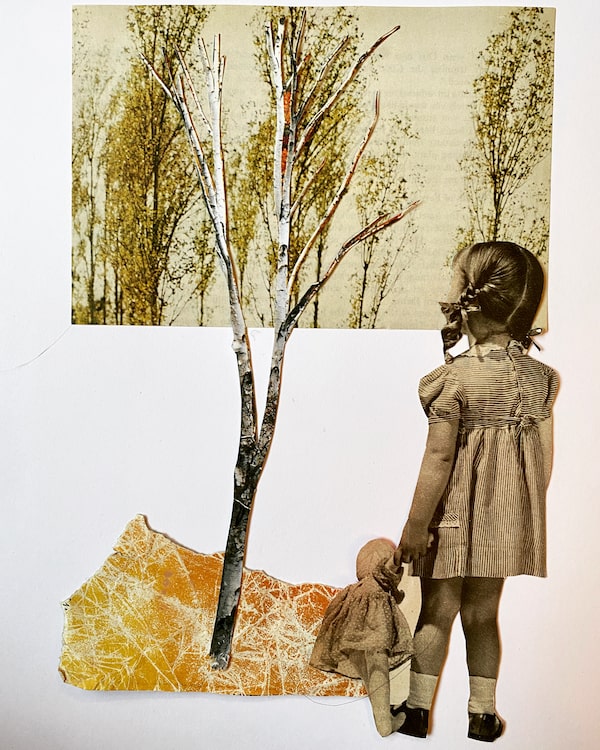

A collage entitled A Year of Leaves, made by author Camilla Gibb.Camilla Gibb/Supplied

For a long time, Canadian novelist Camilla Gibb worried she would never be able to write fiction again. The emotional collapse she experienced after being left by her wife weeks into Gibb’s pregnancy was profound and all-encompassing. Writing fiction, she feared, would be collateral damage.

“I really struggled with the idea of what we can hold onto as true because of events in my own life,” Gibb, the author of four previous novels, said in a recent interview from her home in Toronto. “And I began to distrust many things, including fiction. And what does it mean to distrust fiction? … You have to agree to collude in the fantasy that you’re being offered, in a sense, to participate in fiction, I think, as a reader. And I was unwilling as a reader and as a writer for some time to willingly participate.”

She recounted these events in This Is Happy, her searing 2015 memoir. “Writing once fulfilled so many needs that could not otherwise be met. I am bereft without it,” she wrote.

Writing the memoir was one thing, but creating new fiction was a different story. Still, Gibb managed to write another novel – a testament to resilience, the human spirit, the craft that drives her. It took her six years – the longest it has ever taken her to write a book – but The Relatives was published this spring.

“You will note that my last work of fiction came out 10 years ago. And you will note that I have a 10-year-old child,” she says.

Like her memoir, The Relatives draws inspiration from Gibb’s own experience of motherhood.

The novel follows three separate stories: those of Lila, Adam and Tess.

Lila is a Toronto social worker with a marred record who is nonetheless assigned a challenging case. Robin, as the authorities have named her, was found wandering in her pyjamas in High Park months earlier. And she hasn’t spoken a word. A dental exam reveals she is about 11. Lila, who is dealing with her own grief – the sudden death of her (adoptive) mother – finds a way to communicate with Robin: through music. She becomes invested in Robin’s case – maybe too invested. Which had been her professional downfall previously.

Adam is a U.S. operative – a spy – assigned by the State Department to a refugee camp in Ethiopia, where, undercover as an interim deputy logistics co-ordinator named Daniel, he is investigating rumours that militant recruiters posing as refugees had infiltrated the camp. Then a dangerous thing happens: he falls in love. Sofie is a pediatric nurse specializing in HIV and AIDS. Caring for her makes him vulnerable – with severe consequences.

When we meet Tess, she is on a Greek Island for a summer visit with her seven-year-old son, Max. Tess, an academic, studies isolated islands – but she has a familial connection to this one. They are preparing to return to Toronto when Tess hears from her ex, Emily – Max’s other mom. Emily would like Max to have a sibling. And there are still some frozen embryos from when Tess and Emily were together.

Linked in a way I don’t want to give away (although the jacket’s inside flap spoils it – so don’t read it!), the three stories are each compelling. So when it’s time to move onto the next, there is a moment of withdrawal before quickly becoming engrossed in the next tale.

A central question is: What does it mean to parent? And, as Lila thinks at one point: “What is the point of a human life unrelated to any other human life?”

Collage entitled Wonder, by author Camilla Gibb.Camilla Gibb/Supplied

Even with her own experience to draw from, Gibb found the return to writing fiction to be a struggle. “You’ll notice this was a short book. And I can’t say it was easy,” says Gibb, 53.

“It was a very different process from any other book I’ve written,” she continues. “It was really slow. Every word has to matter. I think it’s not economical exactly. It’s spare, but deep. And it feels true to me, which is a funny thing to say. These people feel very real to me. … It’s probably true that apart from my very first novel, which is also short, that the characters have never felt so real. So maybe that was the truth I was seeking in writing it. But it was not easy to get it out of me.”

Gibb was nearing the final editing stage of the project when the pandemic shut down the world last year. Had COVID-19 hit at a different point, this book might never have been born. Again, she has had no appetite for fiction – writing or even reading it.

“I think had I been at an earlier stage, had I not been able to see the end, had I not known there was a publication date, were we not heading into the nitty-grittier editing, I think I just would have had to walk away. And would I have come back to it? I don’t know,” she says. “Because I’m not really reading fiction; I have no impulse to write it.”

Gibb has been exercising her creativity during the pandemic by making collages that she has been sharing on Instagram. Clever, whimsical – and sometimes dark – they have offered her an outlet and a creative project to embark upon with her daughter, who has been home from school for much of the past year.

With a child at home, writing fiction became impossible once again. “The idea of divorcing myself from this reality and going into another imagined landscape, it’s not really an option,” she says. “The best I can do creatively is take a pair of scissors and a glue stick – something I can do when a child is in the space or I’m worrying about whatever it is I’m worrying about, whatever pedestrian thing to get us through the day. That’s the only way I’ve been able to tap into some other way of seeing.”

Collage entitled Camouflage, by author Camilla Gibb.Camilla Gibb/Supplied

Other new Canadian Mother’s Day reads:

My Mother’s Daughter: A Memoir of Struggle and Triumph

By Perdita Felicien

So captivating is the story of Cathy Felicien Browne’s life – her love-filled but impoverished childhood in St. Lucia, followed by a roller-coaster relocation to Canada – that by the time her daughter Perdita runs her first sprint halfway through the book, you might have forgotten all about the fact that the author is former World Champion hurdler Perdita Felicien. As Felicien begins her track and field career, the book takes off into a new direction, but family – her mother, especially – is always the anchor. It is clear where the Olympian gets her strength and spirit. And while Felicien made headlines for a devastating crash at the 2004 Athens Olympics, it was hardly the worst thing to happen to her; not even close. Her mother’s life, as she writes, was heavy and difficult – and Perdita experienced it with her. “You think this is a bloody joke?” young Perdita witnesses the man she calls Dad say to her mother, as he throws her belongings outside onto the driveway. “You clean people’s toilets. What do you know about anything?” In this inspiring memoir, Felicien – who studied non-fiction at the University of Chicago’s Writer’s Studio – recounts the despair and the triumphs like a champion.

This One Wild Life: A Mother-Daughter Wilderness Memoir

By Angie Abdou

After a couple of debilitating rounds of social media mobbing, Abdou – who lives in Fernie, B.C. – finds solace IRL: in nature, with her family. Do you ever feel “like if you get lost in your admiration of nature, you can forget all of the silly stuff you usually worry about?” she asks her son during a family hike. She dreams up a plan: a summer of weekly mother-daughter hikes, to promote bonding and healing and to help Abdou find perspective. Abdou picks herself up, puts her phone down and heads out into the mountains – where the elevations are high, along with the stakes. And the rewards? Astronomical.

Catalogue Baby: A Memoir of Infertility

By Myriam Steinberg, with illustrations by Christache

Infertility is a heartbreak made worse by the punishing silence surrounding it. In this graphic memoir, Steinberg, who lives in Vancouver, lays it all out – from her desire, at 40, to have a child on her own to the search for sperm donors, multiple medical procedures, devastating setbacks and, finally, resolution, nearly five years later. Along the way, there is a menacing biological alarm clock, turkey basters, a rabbit in need of rehabilitation and a lot of blood – with no-punches-pulled illustrations. “There is so much silence around the pain that can accompany miscarriage and difficulties in conceiving,” Steinberg writes. “I hope this book will help destigmatize a terribly lonely experience.”

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.