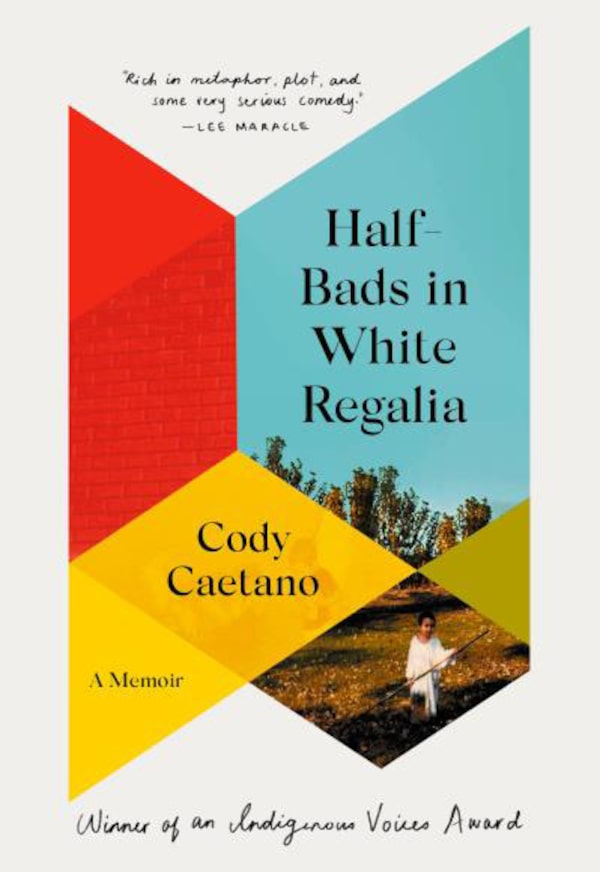

In his debut memoir, Cody Caetano – the son of a Portuguese-Azorean immigrant father and mother who didn’t learn of her Anishnaabe heritage as a Sixties Scoop kid until she became a mother herself – describes, in idiosyncratic slang of his own making, a tumultuous childhood where lack of stability was the only constant.

For long stretches, young Cody and his two older siblings live parent-less in a decrepit house at the side of a highway in southcentral Ontario, euphemistically dubbed “Happyland,” where they distract themselves with video games while pipes burst, mould grows on walls and the burdock in the yard outside slowly encroaches. To help them squeak by, his sister, Kris, drops out of high school to take a job at the nearby casino.

And yet Half-Bads in White Regalia isn’t a gloomy wallow. Writing in dispassionate, hyperbole-free prose, Caetano seems more like a documentarian, recording few apologies, but, remarkably, abundant love and acceptance.

Why did you write this book, and why as a memoir?

Jeanette Walls’s The Glass Castle was the first memoir I encountered, when I was 16. I’d read some Paul Auster, Jerry Spinelli, stuff like that, but The Glass Castle showed me the possibility of memoir and what T. S. Eliot calls objective correlatives: Walls could capture emotional truth and these moments that so often get overlooked in life. The memoir is very proletariat. It’s the people’s art. The abstraction of fiction is near and dear to me, but memoirs are something I’ve learned from. Over the years, I read everyone from Mary Karr to Frank McCourt and saw how these were just regular people who had gone through some pretty particular circumstances and were able to share them with confidence and fearlessness. I knew after reading The Glass Castle that I was I was going to do that too. This story changed over time, from the first draft to now. I wrote it so that the next generation has it. You always work towards making the future better off.

You use a lot of unique colloquialisms in the novel. What, specifically, are half bads?

At first I understood “half bad” as a person who makes mistakes but recognizes those mistakes. Knows them intimately and contends with them. And I think that in the reader’s psychology it contrasts quite nicely with the “baddie” – someone who makes mistakes but doesn’t really recognize them. And I knew it might make sense to readers, especially in our contemporary context, where we encounter cautionary tales and tales of human error both in the public eye and in our own lives and we assess the person through that moment, through that repeated mistake. I wanted to treat that human error like an entity that could strike any of us at any moment.

I also see it as like a wink to the story’s orality. How the narrator uses syntactical riffs and all these fun little things that I hope are exciting for a reader. It’s the way the narrator outfits this story. It could have been told in a much more hefty, intense way because of the experiences in it.

You talk about the narrator – which is you – and your family members in the third person, as if you were characters.

I guess it’s to keep reverence for the people my family are. After that house we never were that unit of five again, but we’ve always maintained tight connections with each other. Even though it’s a story of my life, it’s just one way to tell that story. It’s not definitive. My family have undergone so many changes in the last decade, and it’s meant to just be a very specific part of time. The characterization and colloquialisms are a sort of enshrining of the child’s perspective and voice of the book.

Has your family read it? If so, what do they think?

I feel privileged and lucky, because my family is so supportive. They really get the mission of the book, a big part of which is what Mary Karr, author of The Liars’ Club, calls the subjectivity handshake. It’s a way you can tell a story without being assertive. My job is not to judge or be assertive, like: This is how things went down – even though I can back the book up. I did almost a decade of research and lived the damn thing. But my family understands that it’s one way to tell the story, and it’s imperfect and incomplete. They’ve read it many times and offered so much feedback. There were so many interviews.

In the book you seem happiest when playing video games. Do you still play?

Yeah. With the pandemic they allowed me to spend time with loved ones and close buddies. My brother and I play games all the time. And I play with my nephews now, which is a pretty cool generational thing. Games were very informative and instrumental for me as a young boy. I think a lot of people have hesitations about them, and that’s totally fair. Games now can be very exploitative. The economic model for a video game is much different than when I was younger, but I don’t see them any less potent than I do rap albums. To me they’ve been instrumental to the way I write and think.

I’m assuming the research process meant revisiting some painful events and memories. How was it?

It wasn’t like therapy. It wasn’t meant to be a testimony of resiliency, or witnessing. It was interesting to be brought to moments in which I was not present, when I wasn’t yet born. I had a really good reflection with going back and trying to understand the previous generations and intergenerational attachments. That was a long process, and it’s tricky, because everybody’s got a different way to tell the story. So much has gone down for me to even end up talking to you right now. I’ve never lost sight of that, and it’s been a lot of fun.

In your acknowledgments you encourage writers to try to maintain the sovereignty of their stories. What do you mean by that, and do you think you achieved it yourself?

To achieve the sovereignty of a story is to enshrine it with dignity, to give it what it deserves. I didn’t feel pressured to compromise on this story. And I’ve gone through many institutions to get it to where it is. I’ve gone through universities, I’m with a boutique imprint of a major conglomerate publisher. I get the role I play and how I’ve had to get there, but I haven’t encountered many times when I was getting blocked. Nobody ever tried to make me change it into something that it wasn’t. My mentors, my teachers, my editor, my publisher – everybody has been incredibly supportive and wanting to help me tell it the best I could. David Ross was excellent – he’s such a generous and astute editor. So to answer your question I would say that yes, I think I did achieve it.

You wrote parts of the manuscript under the mentorship of [the late] Lee Maracle. What did you get out of that collaboration?

So much. I’m not sure why she agreed to mentor me, but she saw something in the manuscript. She’s very fierce. She won’t take any anything that feels insecure. So she would ask me very clear questions like, why are you writing this story? And I would give her some weaselly answer and she would ask again and again. She was not allowing me to give in to my insecurities. There’s no time for those. She would make me read to get the orality, so I would read whole chapters with her line by line and she would she would help me figure out the rhythm of the sentence and the structure. She really wanted to train me as a storyteller, to make me recognize the importance of a story and to hold it with a lot of respect. She taught me that stories don’t go looking for people to write them down. Stories come to us. She made me think of it like a little baby, and to hold that baby up – that story up – so that one day it’s going to grow into something and have a life of its own.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.