My encounter with the history of facts began when the professor four doors down – Keith Oatley, a novelist and psychologist at the University of Toronto – sold his house to move into a condo. The downshift meant he had to cull 80 per cent of his sizable library. In private, he admitted that the process was crushing him. You'd see him on the street, taking breaks, scratching his neck.

And so, as he spotted me walking by his house one Saturday morning, he stepped onto his porch and asked – and he didn't waste any time about it – if I wanted a 10-volume set of Chambers's Encyclopaedia, published in Edinburgh between 1888 and 1892. Red leather, fine condition, stamped with gold. The set weighed 40 pounds and demanded four thick feet of shelf space. The books resembled the foundation of a small shed.

I knew I ought to say no. A set of Victorian encyclopedias, in the age of Wikipedia, in my smallish house, where our own books were already shelved two rows deep?

"Are you insane?" my wife said, as I staggered through the door with my prize.

The box went into the sunroom. It moved from there to the basement and then back to the sunroom. It spent some time on an armchair in the living room. For the past two months it has occupied the trunk of our Toyota Camry.

The local second-hand bookstore will take anything except hardcover novels and encyclopedias. The Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto already has a set.

Why can't I throw them out? They are technologically redundant and epistemologically out of date. They are often short-sighted, frequently racist, and sometimes just plain wrong. Did I mention they take up a lot of space?

But: They are filled with facts, 10 bound volumes dedicated to the idea that the details of human reality and history can be pinned down, stored, referred to, and even updated, thereby guaranteeing that our state of being on this planet is a knowable, reliable, transferable entity.

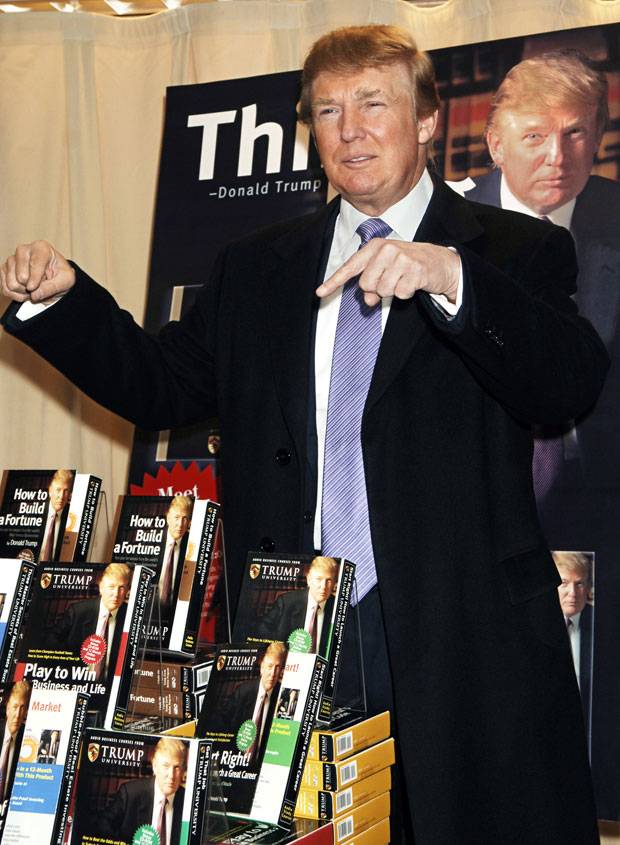

My encyclopedias also remind me that facts, as a body of knowledge, have a history of their own – and not a long history, at that. Strongmen have always tried to subvert democracy and distort reality by attacking the media and suppressing facts, and seldom more widely than right now, when authoritarianism and its disdain for facts and freedom are enjoying a worldwide moment. Vladimir Putin and Polish president Andrzej Duda, with whom Donald Trump has been buddying around all week, are famous for it, and so are Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the Saudi royal family, also Trump friendlies.

But now that even the President of the democratic United States prefers to deal in alternative facts – about climate change, the prevalence of crime, the extent of terrorism, the size of his modest inauguration crowd, and somewhere north of 350 others since the inauguration – I thought it might be wise to hang on to a set of originals.

Self-improvement, page by page

In the evenings, after I have caught up on my television viewing, I flip through my new (old) encyclopedias. A handwritten letter from the binder, dated Feb. 17, 1893, apologizing for how long said binding has taken, is tucked into the front flap of Volume I, which opens with a disquisition on the letter A, and closes with an entry on Beaufort (not the sea, but the cardinal and three-time Lord Chancellor of England who for most of his life was the wealthiest man in the country). The entries are written with confident purpose: The subtitle of the encyclopedia is A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge. This is all you know, it implies, and until a new updated set of facts comes along, all you need to know.

The heyday of encyclopedias lasted something like 130 years, from about 1780 to the outbreak of the First World War. Like most of its competition, the Chambers's Encyclopaedia (named after William and Robert Chambers, Scottish brothers, both of whom had extra digits on their hands, and the latter of whom was a proponent of evolutionary thinking) was published in 520 weekly instalments and sold to (mostly) upwardly mobile middle-class subscribers at three halfpennies an issue. When you finally owned the full set, you had them fancily bound with the same lavish care you might once have bound the family Bible.

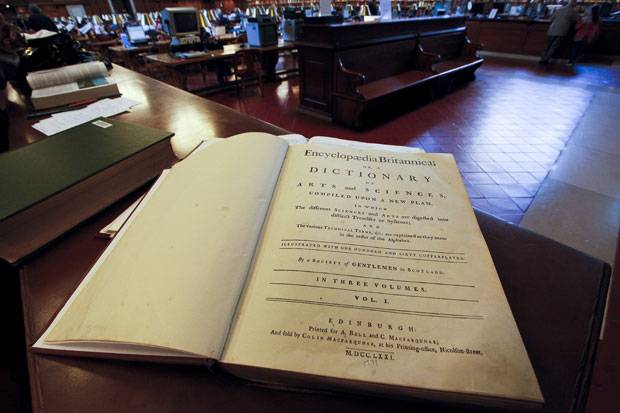

My set – roughly 8,300 pages; 85,000 entries; 10.3 million words; 200 contributors – was the second, or "new," edition, updated and augmented (especially with American data) in Edinburgh, the birthplace of both the Scottish enlightenment and the Encyclopaedia Britannica, which first appeared in 1768. The Chambers's was less academic and opinionated than the Britannica, but both were proud products of Scottish Presbyterianism. Facts, and the education and hard work of learning they implied, were the route to self-improvement in Calvinist Scotland, and therefore the path to God. The rise of fact-filled encyclopedias was matched by growth in trade unionism and night schools. Everyone was into self-improvement.

Encyclopedias were not new, of course. Pliny the Elder hadn't yet finished writing his Naturalis Historia when Mount Vesuvius engulfed him in lava in AD 79. But premodern encyclopedias were produced for other encyclopedia makers, rather than for average users – a way to pass along an age's collected known facts, so that, as the French encyclopedist Denis Diderot said, "the mark of preceding centuries will not become useless to the centuries to come."

This is still the case. "We'd never want to say, 'We know the whole truth,'" Pearce Carefoote, director of collections at the Fisher, told me the evening I called him to see if he could help explain the appeal of my inherited encyclopedia. "But each successive edition of encyclopedias has yielded another body of knowledge to pass along. We wouldn't be able to do what we do today without them. The Internet is not possible without them."

Encyclopedias were a way to classify facts and knowledge, to organize what we knew, in the most satisfying, alphabetical way. (Hello, fellow nerds.) But commercial printing presses made the facts in modern encyclopedias more available to more readers – and therefore more dangerous. The word

fact doesn't come into common usage in English until 1660, with the establishment of the Royal Society, which was devoted to the newfangled scientific method. David Wootton, a professor of history at York University and the author of the excellent The Invention of Science: A New History of the Scientific Revolution, points out that "in the 17th century, the nature of information changed: As information became more reliable, authority became less so."

Human society has always trafficked in theories and hypotheses and opinions – that a murdered body would start bleeding in the presence of a murderer, for instance; that the sun revolved around the Earth; that the king was divine. But facts, pieces of information presented as objective reality and backed by testable scientific evidence, were much rarer. As Prof. Wootton points out, a hypothesis is always a hypothesis, however dumb (Barack Obama is a Muslim born in Kenya); a fact that has been proved wrong is no longer a fact (his birth certificate proves he was born in Hawaii). Rumour, opinion, hearsay, magic, the infallibility of reputation, and all the other shaky foundations for what men and women for centuries believed to be true, were by the late 1700s fading from use. The experimental method and the rational use of provable facts were moving in instead.

Which was why Denis Diderot's infamous Encyclopédie caused a scandal when it first appeared in 1751. The Catholic Church hated it, because it used proven facts to undercut the faith-based authority of priests. Several of its editors went to jail, as did the encyclopedia itself on several occasions. Louis XV didn't like it much either, but after he referred to it during a dinner party, to resolve an argument about the components of gunpowder, he prosecuted it less. The French Revolution occurred 17 years after the complete Encyclopédie appeared, for not unrelated reasons.

Across the English Channel, the first three volumes of the Encyclopaedia Britannica were published between 1768 and 1771. It was immediately branded the "Gospel of Satan." Even doctors denounced the Britannica: They resented its undermining of their authority (just as many doctors resent patients resorting to the Internet today). Suddenly, evidence-based knowledge was a source of power not just to a profession or a ruling class, but to anyone who could read.

And facts could be passed on, another alarming development. To believe that the knowledge you have is worth passing on, you have to believe in the future – that is, in something other than power at all costs.

The reams of facts in my box of Chambers's have an often maddening certainty, especially on details subsequently revealed as wrong or prejudiced or simply too much the status quo. (The entry for Negroes, in Volume VII, holds that such people "gradually but surely perish" in Canada, due to the cold, and that – this is one among other egregious statements – "the negro is ambitious for education, but unwilling to make the necessary mental effort to obtain it.") The heading on electricity (electricity was the driverless car of the Victorian age, along with more efficient munitions) is 23 pages and 10,000 words long.

There is an entry on abbreviations (in 1888, BVM stood for Blessed Virgin Mary; SP denoted sine prole, or without offspring), and another on abortion (still to remain illegal in Britain for a very long time). I discovered, thanks to several pages on the subject of swearing, that Pythagoras swore on the number four (as in, "I swear by the number four that I have been on the cover of Time magazine more than any other president"), and that Queen Elizabeth (the first one) had a potty mouth. I had not known that sweet potatoes are of the genus Batata; or that the 4,500 inhabitants of Zyrianovsk, a silver-mining town on the southern frontier of Siberia, and the last entry in the encyclopedia, were "shamanists" who "live by hunting in the forests."

And I am not even mentioning the cast of eccentrics (mostly journalists) who actually wrote the encyclopedias, such as the one-eyed journalist James Tytler, an Arctic whaler and one of Britain's earliest hot-air balloonists, who later drowned, drunk.

Mostly, I like the modesty these thick books imply: The world is a vast and complex place, and understanding it is going to take a while, and several attempts. No one need pretend to have all the answers, or to be absolutely certain of anything. We can look it up.

Prejudice, evidence, truth

Where do Donald Trump and other world authoritarians fit into the history of facts? It's fashionable these days to claim that Mr. Trump and his ilk are supersophisticated "posttruth" types, that they have expropriated the terrain of postmodernism and seized the handy high ground where everything is relative, where the truth is simply what you can convince people of. But within the history of facts, the 45th president is actually a throwback, an atavist of a more primitive consciousness. And it is digital-information technology that has allowed him to be that way.

At the outset of the encyclopedia movement, in the latter half of the 18th century, encyclopedia makers "had the sense that they had enclosed language," Prof. Carefoote, of the Fisher, told me. "And they were very proud of that." They had tamed the world by organizing their knowledge of it into strict alphabetical categories.

That was the appeal of a brand-name encyclopedia, and the secret weapon of Edinburgh publishers who produced the English world's most famous ones, according to Stephen Brown. Another scholar of the history of facts, he teaches English at Trent University in Peterborough, Ont. Journalists wrote many of the entries in the Britannica and the Chambers's, but as reading material, those entries were considered a cut above magazines, more permanent and thoughtful than the rough and tumble of pamphleteering and newspaper writing. "Eventually, the publishers who made the most money realized that reliability was profitable. The Chambers brothers knew that."

They were subject to the prejudices of their time, but had faith that a belief in evidence would eventually reveal those prejudices, and clarify them, thereby transforming information into knowledge. "Information is what you bring to the conversation," Prof. Brown observes. "Knowledge is what you take away from it."

But digital technology has subverted that certainty. Today, Prof. Carefoote says, "in a way, we're almost doing the opposite. Now, thanks to computers, we've broken the bonds of confining information. Everything can be linked beyond the bonds of the text." Or, as David Wootten put it recently in Modern History, "in the print world, getting your facts right was about competence and care; now, what the facts are depends on what date you access a website, or which website you visit."

Eventually, I called Keith Oatley, the man who had given me the encyclopedias. I asked how he was, and he said, "Getting on." He claimed to have recovered from his book culling. I told him I was enjoying the encyclopedias, though their earnest fact-listing seemed a little old-fashioned, given that a lot of people believe Donald Trump's lies simply because he's the President, or because a pro-Trump website like Breitbart insists they are true.

Prof. Oatley scoffed loudly into the telephone. "Real information," he reminded me, "real evidence, is something that has only very recently become of interest to people." The first truly important testable evidence in medicine turns up, he insisted, as late as 1849, when John Snow discovered that diseases such as cholera were caused by something other than "miasma," or vapours in the air.

Galileo had introduced evidence to physics for the very first time only 150 years earlier, and for his trouble was placed under house arrest for the rest of his life. As for the law, Prof. Oatley said, it is still relatively evidence-free. "Even in a jury trial, what the jury is really doing is comparing two stories, and deciding which they like better."

Facts can now be fished instantly from a wide range of invisible sources (from sites like Breitbart, which seems to openly invent news, to The New York Times, which tries not to), but that doesn't mean everyone has the skills to use facts properly. "The encyclopedia became a technology," Prof. Oatley reminded me. "It was the reason you and I didn't have to travel to Alexandria" – the site of the world's first library – "to look something up."

Donald Trump, on the other hand, is an incompetent user of facts. "He's a barely educated person," Prof. Oatley continued. "He doesn't read. He doesn't have much of an attention span. He's a throwback to an earlier age of gossip and oral communication."

And Twitter, his main vehicle of expression, is nothing like an encyclopedia. "Twitter is some sort of Internet version of shouting your mouth off. That's what happened 500 years ago. Someone says, 'Shakespeare's an asshole,' and someone else says, 'Yes, I think Shakespeare's an asshole, too.' Twitter is a form of gossip. What gossip is, by a psychologist's measure, is some way to enter an idea into someone else's model. That's been going on for thousands of years. But it isn't really information."

It isn't fact, either. This is why it's important to understand Donald Trump within the context of the history of facts. He's not a sophisticated postfactual postmodernist. He's a throwback, not just beyond the rationality of Voltaire to the emotionalism of Rousseau, but way, way, waaaaaay back, to pre-Enlightenment mystical shamanism, to the credulous world of shadows inside Plato's cave, to abracadabra and the wowza flash of fire.

Look at his tweets if you don't believe me. Does he make a factual case for American industrial rejuvenation? No, he reverts to preliterate chanting, like a witch doctor, merely repeating the same phrase over and over: MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN! He even wears a Scowling Mask as he dances round the fiery light of his cellphone on Twitter.

Does he calmly argue the factual or statistical likelihood of his Russian connections – if they exist, of course – actually being able to steal an election? No. He reverts to primordial diversionary tactics, subrational, even infantile tit-for-tat and nyah-nyah about the alleged degradations of the Hillary Clinton campaign and the Obama years.

Does he lay out factual evidence that the mainstream media may be compromising their objectivity by assuming the role of official opposition to the White House? Nope. He just calls them names, grunting out labels like "Fake News!"

Does he analyze terrorism or immigration factually – gradually and carefully compiling an encyclopedia of evidence about why a few people commit unspeakable acts, while most don't? Not unless "evil losers," his label for the Manchester bombers, counts as factual. And when he knowingly tosses out an obviously subrational idea – covfefe! – his handlers claim it's full of meaning, albeit only to a few geniuses.

The wizard farts, but only other wizards understand the true meaning of the noise.

Donald Trump – to say nothing of his fellow authoritarians – may be resorting to alternative facts, in other words, because he doesn't know how to use real ones. He is not a postinformational man; he's a prefactual chimpanzee, and even that may libel chimpanzees.

At least, that's what the history of facts tells us. And that seems to be the truth.

Ian (Encyclopedia) Brown is a feature writer for The Globe.

WHAT IAN BROWN'S READING: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL