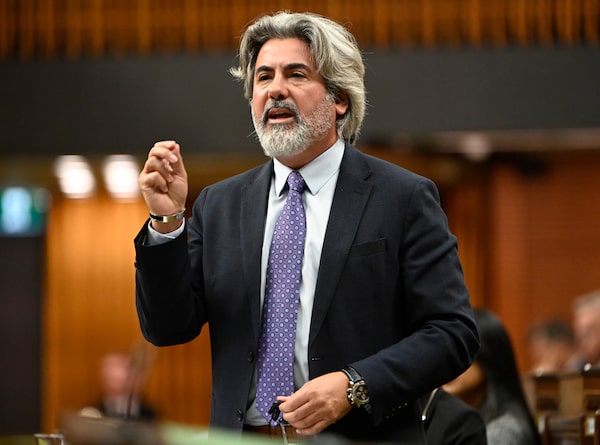

Minister of Canadian Heritage Pablo Rodriguez.Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

While Steven Guilbeault is busy saving the planet, can Pablo Rodriguez clear up the little mess his colleague left behind at Canadian Heritage?

This is the second time that the loyal and reliable Rodriguez has been called on to take over much-needed updates to Canadian cultural policy.

He was appointed Minister for Canadian Heritage in Tuesday’s federal cabinet shuffle, replacing Guilbeault who, just prior to September’s unnecessary election, had done a poor job explaining proposed changes to the Broadcasting Act. (Guilbeault, a former environmental activist, was just handed his heart’s desire in the shape of the Environment portfolio: one now hopes he will do a very good job explaining climate action.)

As for Rodriguez, he has been here before: He also served briefly as heritage minister from 2018 to 2019 after Mélanie Joly (now surprisingly elevated to Global Affairs) left the portfolio with her grand ambitions for digital-era cultural policies largely unfulfilled.

Canada’s once-enviable legal supports for domestic culture have been bypassed by the borderless digital giants – Netflix and Spotify know no Can-con rules – and, you’ll remember from previous episodes, Joly had raised expectations of a big fix with her big cultural-policy review. Yet, when she finally unveiled proposals, they turned out to be mere tweaks: The minister had failed to deliver.

When Rodriguez took over in 2018, the main expectation was that he would keep things quiet on a potentially unpopular file in the runup to the 2019 election: Canadian consumers are easily spooked by any change they think might impinge on cheap and continuous access to Hollywood product. Rodriguez did avoid controversy but he also sent strong signals that the government was finally ready to move. All players who make money in Canada will contribute to the Canadian production system, he promised.

After the 2019 election, he was shuffled again and it was the newly elected Guilbeault who stepped in, ready to prove himself in what many governments mistake as a minor portfolio. (The budgets may be small but the potential for both nasty blowups and reflected glamour of the arts world is real.) Guilbeault initially performed well, proving a strong supporter of the cultural sector, less prone to Joly’s digital-era burbling and the ministry did, at long last, table a bill to update the Broadcasting Act.

Bill C-10, which gives the government the right to regulate commercial content on digital platforms, was introduced by the Liberals a year ago and supported by both the NDP and the Bloc Québécois. It’s widely viewed as a logical if very belated next step by the screen industries and the music business. However, internet activists of an alarmist and libertarian bent raised the spectre that the proposed law could be used to regulate social-media posts.

The Tories, spying political opportunity, began fanning those flames, and Guilbeault was caught unable to explain how he would make the distinction between your home movies and professional music videos on a service such as YouTube. The Senate, smelling public discomfort and confusion, then dug in its heels last summer and said it wanted more time to consider all the implications, ensuring that the bill died on the order paper when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called the election.

No doubt Guilbeault is better acquainted with calculating the effect of carbon offsets than broadcasting regs, but could his lack of oomph in the final push simply be attributed to his province? Trudeau has picked all his Heritage ministers from Quebec, a society that equates culture with survival, and many Quebeckers simply couldn’t understand opposition to C-10.

For example, requiring that Netflix not simply spend production dollars shooting in Canada, but also create Canadian shows – including ones made in French – is the only way Quebeckers will get a useful Netflix: Right now, the streaming service is a portal to original English-language content, leaving francophones listening to dubbed versions or watching a handful of French-language shows that mainly hail from France.

Europe, meanwhile, is now implementing its 30-per-cent European-content rule for services such as Netflix, Disney+ and Apple TV while France has also set a local-production investment requirement of 20 to 25 per cent of the services’ revenues.

Here in Canada, the difficulty with having a Quebecker lead the charge is that bringing these services into the fold doesn’t need to be sold to true believers in Quebec but to skeptics in the rest of the country.

Rodriguez is another Quebecker but also an Argentine immigrant who is trilingual in French, English and Spanish and has a reputation for political smarts: Before his first term in Heritage, he was chief government whip; when the past election was called, he was government leader in the House. As Rodriguez returns to Heritage, Canada’s cultural producers are praying that he is the charm.

Sign up for The Globe’s arts and lifestyle newsletters for more news, columns and advice in your inbox.

Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor