Michael Schur speaks at Universal Television's The Good Place FYC panel at UCB Sunset Theater on June 17, 2019 in Los Angeles.Rachel Luna/Getty Images

Spotify is standing by Joe Rogan, though it has removed 70 of his podcasts that contain racist language. Whoopi Goldberg is spending two weeks away from The View after making wrong and hurtful comments about Jewishness – but she’ll return. Chris Noth was excised from the final episode of And Just Like That, after three women accused him of rape and sexual misconduct. The first two episodes of W. Kamau Bell’s documentary series We Need to Talk About Cosby arrived on Showtime/Crave, taking a hard look at the disgraced comedian’s legacy. And that’s just in the past two weeks.

Thanks to social media, we’re flooded with information about the sins of others, all the time. We can no longer be blissfully unaware of the bad things that our once-favourite actors, musicians, athletes, et al have done. We can no longer enjoy art without considering the artist. Yet we have no universal standard for which wrongs are forgivable and which aren’t.

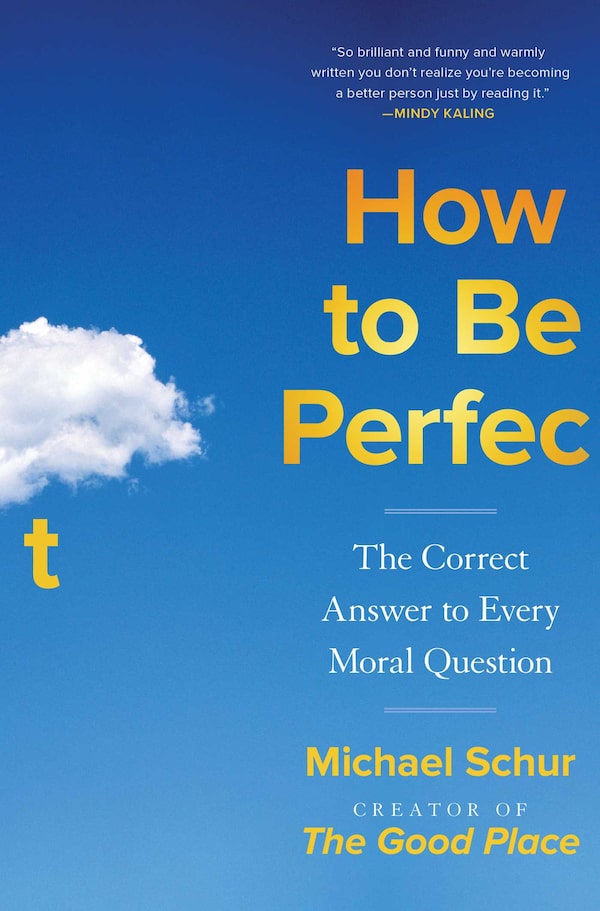

That’s why I jumped on Michael Schur’s new book, How to Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral Question. Schur, 46, is one of my favourite television writers, because the series he cocreated – including Brooklyn Nine-Nine and Parks and Recreation – embody an idea that’s close to my heart: People behaving well can be just as dramatically interesting as people behaving badly.

In his most recent series, The Good Place, Schur did a deep dive into philosophy and forgivability – and when the show ended, he kept writing. The resulting book is fascinating, and Chapter 10, entitled This Sandwich is Morally Problematic. But It’s Also Delicious. Can I Still Eat It? is especially, screamingly relevant. It tackles so-called cancel culture, and offers guidance on how to navigate it. Not surprisingly, it was the hardest chapter to write, Schur told me in a recent phone interview. Here are highlights from that conversation.

Please solve these conundrums once and for all: Can we still listen to R. Kelly, watch Johnny Depp and Woody Allen, laugh at Dave Chapelle and Bill Cosby, read J.K. Rowling – to name just a few people who’ve done morally problematic things – and can and should we forgive them?

My answers will be frustrating. [Laughs] Not even the world’s greatest ethicists can satisfactorily answer the questions of what’s okay and what isn’t. It’s just grey and mushy and hard and weird.

Well, that’s sobering.

You have to ask yourself what you think is right and wrong, based on your belief system. You draw a line and determine for yourself if a person crossed it. There is a difference between Harvey Weinstein – extreme outliers of horrifying human behaviour, who dug such a deep hole of pain, suffering and sadness that humanity has no debt to forgive them – and a generic stand-up comedian who does a three-minute bit that’s offensive to a group of people who’ve been marginalized.

But part of the gears grinding in our new world is that at the surface level, all these crimes land with the same initial impact: Everyone is talking about it on Twitter, writing blogs, freaking out. We’re grabbing all the people who have done anything wrong, and exposing them in roughly the same way. That’s not discerning, it’s not a good analysis of behaviour.

In his most recent series, The Good Place, Schur did a deep dive into philosophy and forgivability – and when the show ended, he kept writing.Supplied

You write that to be forgiven, a person has to do certain things, sincerely: Show contrition. Admit your mistakes. Apologize properly. Correct your behaviour. But so many apologies are bad. Rogan, for example, gave a classic nonapology: “I thought as long as it was in context, people would understand what I was doing …”

That’s why the term cancel culture is stupid. It’s consequence culture. People who complain about it just don’t like that there are now consequences to their actions that didn’t exist before. I do think that instead of fists raised, ready to fight, it might be better if our initial stance is to slow down, acknowledge human frailty. We still might find the behaviour unredeemable. But we might tilt the other way on the marginal cases. If a person is appropriately chagrined and redemptive in their behaviour, I may find it in my heart to forgive them.

So what’s to stop us from saying, “I want to listen to R Kelly, so I’ll be generous and forgive R Kelly.”

You have to have a sense of integrity. If you want to listen to R Kelly, knowing that he kidnapped women and held them hostage, you have to admit that to yourself. There are rare situations where someone is so foundational to who you are as a person – like, if you’re a young musician, and R Kelly is the one who made you want to be a songwriter; or like me, I learned about comedy from Woody Allen; or like many people felt about Bill Cosby – that even though you know he’s a monster, the thought of driving him out of your life is sad, because he contributed to who you are. In those rare cases, there are degrees with which you can continue to engage with the art that person made. But you can’t pretend that he didn’t do anything bad. You have to hold both those ideas in your head at the same time: He is a monster, and he is important to me. Because if you don’t do that, you are adding a little bit more damage to the damage already done to people by this person you care about.

I can’t declare where your line is. You have to figure out where it is, draw it, and obey it to the best of your ability. And then, as new information comes to you, you may have to erase that line and redraw it.

The truth is, there’s no direct correlation between bad behaviour and good art. There never has been. That was a complete fallacy: “These people are imbued with this special ability. And because they’re special” – because, say, Charlie Sheen makes everyone so much money on TV – “shh, we have to let him do whatever he wants. He’s a rhino in a china shop, let him break everything and we’ll clean it up afterwards.” No one believes that any more. And there’s a far lower tolerance for terrible behaviour, which is undoubtedly a good thing.

Special to The Globe and Mail

Sign up for The Globe’s arts and lifestyle newsletters for more news, columns and advice in your inbox.