Indigenous advocate, author and broadcaster Jesse Wente on Sept. 2.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

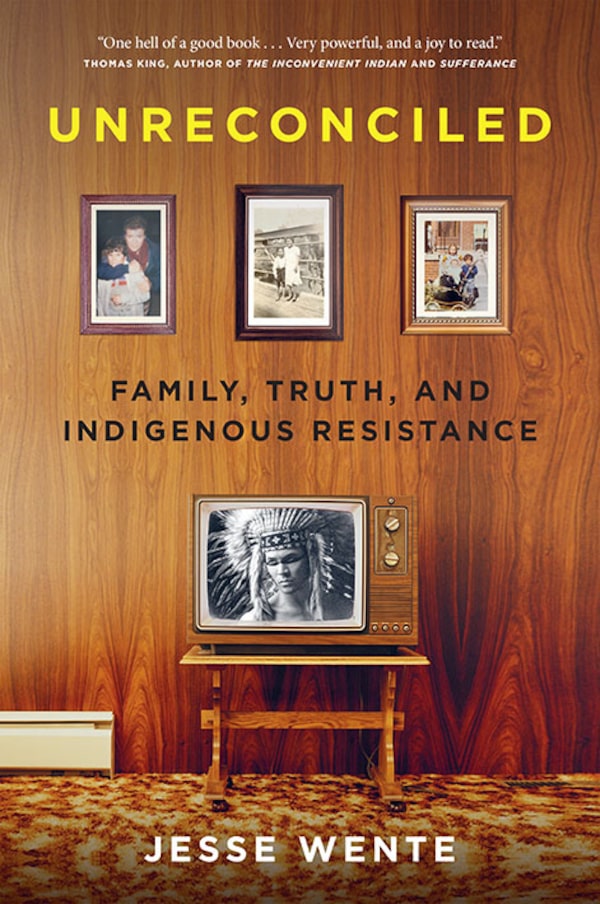

Jesse Wente ambles across the grass of a west-end Toronto park, black mask dangling from a wrist, aviator shades perched on his nose: a portrait of late-summer, late-COVID-era ease. About a month earlier, I’d asked him to suggest a spot where we could meet to discuss his forthcoming memoir, Unreconciled: Family, Truth, and Indigenous Resistance. It’s a slim volume that lands heavily, as Wente, who has always been cautious about revealing personal details in public, shares sobering stories of his past and connects them to the complicated, conflicted feelings he has toward both Canada and himself. I had hoped the location, of his choosing and not far from his home, might help him feel comfortable.

That was probably expecting too much.

Two days before we met, Wente posted a raw disclosure on Facebook. “Depression and anxiety have been my most consistent companions this year,” he wrote. “Anxious about my work, my life, and my place within the community I have worked so hard to be a part of and to serve.” He thanked those who had buoyed him along the way, and added: “I finally feel like I’m finding myself again, even if my self isn’t exactly the same as it was.”

And so, as he settles onto a park bench next to the pool area, he acknowledges that even this encounter is flecked with anxiety. “It makes me a little nervous to show so much,” he says. Still, he’s been in the arts long enough – 11 years as a programmer with the Toronto International Film Festival, two decades as a film columnist on CBC Radio, newly minted film producer, chair of the Canada Council of the Arts and executive director of the Indigenous Screen Office – that he understands the die is now cast. “I’ve been around artists and storytellers long enough to understand that, you tell a story, but once it’s out in the world, it’s sort of not yours anymore. Or, it’s still yours, but other people will make it their own.”

He says this breezily, but there’s an unspoken tension there: People have been projecting their interpretations of Wente onto him since he was a child.

Unreconciled is an attempt to unpack that, beginning with the knotty branches of his family tree. His mother’s mother, Norma, was born in Serpent River First Nation, an Ojibwe reserve on the north shore of Lake Huron. She was sent to a nearby residential school, where she was cut off from her family and traditions and barred from speaking Ojibwe. At 16, she returned home but no longer felt comfortable there. She moved to Toronto, married an army veteran 20 years her senior, took a job as a domestic – the only sort of work for which the residential school had prepared her – and, later, as a hostess at the Albany Club, the venerable private club whose founders included Sir John A. Macdonald.

Wente’s father’s side were of stock that patronized those sorts of private clubs: His father, Jim, moved with his mother and two sisters from Chicago to Toronto in the mid-60s and grew up amid privilege that included a membership in the Royal Canadian Yacht Club. He met Norma’s daughter, Connie, at Toronto’s Malvern Collegiate; they were free spirits and they married shortly after high school.

Wente, his parents and his younger sister, Maggie, would visit Serpent River a few times a year; though he felt a connection up there to his roots, he also felt somewhat alienated. And privilege is insistent: with financial support from his paternal grandparents, he attended Crescent School, located a brief limo ride from Toronto’s tony Bridle Path neighbourhood, where his high school classmates were sons of Canada’s ruling classes. (He learned from them how to adopt a pose of entitlement, which would come in handy decades later when he would stride into boardrooms and make demands on behalf of his community.) In time, though, he began to feel alienated from his fellow students, “othered” by them – and not just when, in September, 1990, as the Oka Crisis lurched into its final month, one of them quipped: “Go back to Oka.” (Never mind, as Wente points out in the book, that he is Ojibwe and the Oka blockade involved Mohawks.)

Even as he resolved to explore his Indigenous identity, to understand what it meant to him, the outside world would impose its own interpretations of that identity upon him. As a young man, he was stopped repeatedly on the streets of Toronto by police, gawked at by tourists, followed with suspicion in stores. He cut his hair, in hopes of gaining some space for himself. “I was sick of being treated as either a threat or a mythological creature, with little room in between to just be myself,” he writes.

As an Indigenous student attending the University of Toronto, he was eligible for federal funding. But he struggled with whether he deserved it. He worried that those in Serpent River “might object on the grounds that I lived in the city, that I hadn’t grown up on the rez or faced the conditions and challenges that too often come with life in a First Nations community.”

I tell Wente that the passage reads, to me at least, as if he is suggesting that to be Indigenous in Canada is to struggle, to be downtrodden, and that his privileged upbringing somehow made him less Indigenous.

“It’s interesting. I had not thought of it that way,” he replies, and I wonder for a moment whether I’ve offended him. “I think there is truth to that. Not that that’s actually true in the real world. I think it’s true that in conception, Canadians – I shouldn’t say ‘Canadians,’ what I should say is ‘Canada’ – prefers its Indians downtrodden,” he says. “But it was not my conception that I was less Indigenous because I was privileged, it was that I might be [less so] because I didn’t grow up in my community, I didn’t know my language, I didn’t know my stories.”

I ask him about the implication of my question: that he might have internalized the notion of the downtrodden Indian.

“Oh absolutely, I think a whole host of us have internalized all sorts of things, just like folks [in Serpent River] have undoubtedly internalized things, too,” he says. “And you know, the book, and my increasing understanding of my life and the journey of it, is trying to make sense, trying to unpack existence, colonized existence in 2021, and what that actually means, and trying to divest from it as much as you can.

“All I can say is that my understanding, my awareness is evolving every moment of every day and I will continue to try to unpack this stuff, so that I can – it’s a loaded word – feel comfortable here. Because if there’s a feeling that I would suggest is the most familiar to me, it’s discomfort.”

As Wente writes in Unreconciled, one of the places where the discomfort finally became too much for him was TIFF. Growing up, he had found great comfort in films, despite the medium’s own deep history of racism, of imposing false and damaging stereotypes onto Indigenous people (and, let’s face it, many others). But as the only known Indigenous film critic working in North America, Wente had brought a unique and vital critical perspective. He joined TIFF as a programmer in 2006 and became the head of its year-round Cinematheque when the festival opened its Lightbox cinema complex in 2010.

In 2017, however, TIFF executives asked for his perspective on a trio of films about Indigenous people that were being considered for that year’s fall festival, including Hostiles, a Western starring Christian Bale as an American soldier who escorts an old Cheyenne enemy (Wes Studi) back home. In a note to his bosses, Wente excoriated the film, calling it “deeply racist” and “exactly the sort of movie that should no longer be made.”

The film landed a prime spot in that year’s festival. Its gala screening was preceded by an Indigenous land acknowledgement that TIFF had initiated that year, part of its reconciliation efforts.

Wente had crafted the wording.

It was all too much. He tendered his resignation.

“I think the point of this section [in the book], as much as the point of the CBC section [in which he discusses episodes in which he felt tokenized], or any of those parts, is that they’re not alone. The takeaway for me has been, it’s going to be hard for me to be in any colonial space and not be tokenized. That’s just sort of been the experience. Because I think [the institutions] have to put effort to not do it.”

Yet, despite those experiences, Wente retains a sort of stubborn hope that things can improve, a legacy he feels might be inherited from his father, whose family saw Canada as a kinder, gentler alternative to the United States.

It’s a quiet day here in the park, and as we talk – our one-hour appointment stretching beyond the three-hour mark – mothers arrive with their children for a swim in the pool. The joyful yelps of the kids cuts through the buzz saw of cicadas and our own conversation. Wente’s son and daughter, now in their teens, used to take swimming lessons here, and his thoughts turn to the next generation, to the possibility of reconciliation, to the children of his ancestors who did not come home from their residential schools.

“I think the book sort of suggests that reconciliation is going to be really hard for this place,” says Wente, inserting an expletive to emphasize the point. “And I think the book also suggests reconciliation for myself has not been all that easy.

“I don’t ever want to say it’s impossible – because the first thing we should be gifting future generations is hope, not despair that things are impossible. But I do wonder, and I would say this is true of both situations, both with myself and with Canada.

Unreconciled: Family, Truth, and Indigenous Resistance is a slim volume that lands heavily.Supplied

“You’re going to be hard pressed to get to reconciliation if you’re not willing to – we’re sitting by a pool – if you’re not willing to jump in the deep end. I’m not sure Canada has truly leapt in. It may be putting a toe in the pool a little bit to figure out what the water feels like.”

I suggest to him that Canada probably believes it’s in the middle of the pool, and pleased with its own progress.

“I think you’re not wrong,” he acknowledges. “But there are things you cannot hide from, and I think Canada has extended an extraordinary effort to hide from some things – to hide them from others, but primarily from itself.”

That is why this year’s revelations of the children buried on the grounds of residential schools shook the country to its core: Canada needs to first reconcile with itself, learn and grapple with its own malignant history, if it has any hope of reconciling with the many first nations that share the land.

We rise from the bench to stretch our legs, and as Wente turns around he spots something tracing an arc in the sky. “Look at that hawk,” he says, a note of awe edging his voice. He is silent for a moment, watching the bird swoop and rise on the wind.

“They would say that’s an omen,” he says finally. “We’re taught that animals have intention. So, when an animal visits you like that, you should actually acknowledge it.

“What the hawk is supposed to teach you is to have perspective. Because the hawk flies very high, it can see very far. So it’s reminding me that – or should remind you too, actually, in this moment – that there’s something that you need perspective on. But there’s another element to the teaching, which is, as high as the hawk flies and as far as it can see, it can’t see past the horizon. So there’s limits to what you can actually know, and what lays sort of beyond.”

Sign up for The Globe’s arts and lifestyle newsletters for more news, columns and advice in your inbox.