Starting this weekend, visitors to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto should be prepared to be overwhelmed upon crossing the threshold of the Zacks Pavilion. That sensation of surge and submersion comes courtesy of Outsiders, a new, AGO-curated exhibition of more than 300 photographs and five films by such American masters as Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, Nan Goldin, Gordon Parks and Robert Frank.

The show's subtitle, American Photography and Film, 1950s-1980s, may hint at the scope of the experience ahead, the ambition of the enterprise. But its just-the-facts blandness in no way conveys the presentation's all-encompassing effect in real time, its power to amaze and perturb. This is a commanding exhibition, drawn almost entirely from the AGO's own resources and those of friends, that demands more than a look-see; it's about looking and seeing and looking again. And that, my friends, can be very exhausting, albeit in a good way.

"Outsiders" implies, of course, its binary opposite, and with it, a dynamic of "antagonistic reciprocity," of "us" and "them." This tension was especially pronounced in the four decades covered by the exhibition's rubric. Simply saying the names of the U.S. presidents who most dominated the epoch should be sufficient to convey the particular textures of those times – Eisenhower, Johnson, Nixon, Reagan. Yet to their credit, the show's co-curators, associate photography head Sophie Hackett and manager of publications Jim Shedden, take a decidedly fluid approach to the theme of outsiderdom. Yes, the exhibition offers a feast of images of myriad subcultures and countercultures, quasi-families and tribes, "defined," variously, by lifestyle, genetics, affinity and/or economic circumstance. We're talking suburban swingers, peaceniks and Russian dwarfs, biker gangs, cross-dressers and hippies, impoverished African-Americans, naturists and individuals with Down syndrome. But we're always made aware that each documentarian here possesses varying degrees of insiderness and outsiderness in relation to what he or she is framing in the viewfinder.

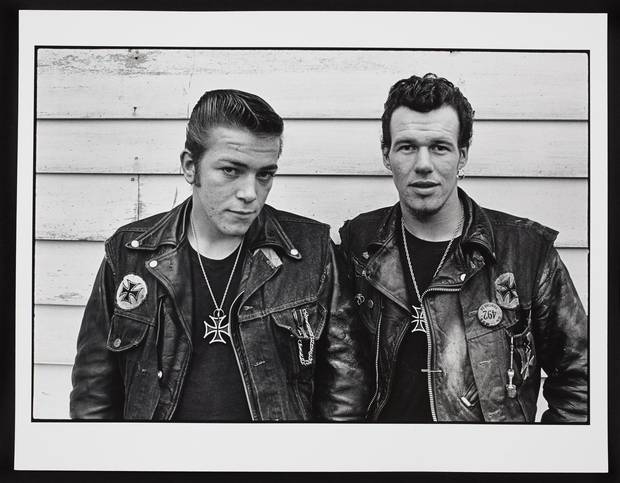

Danny Lyon’s 1966 Sparky and Cowboy.

Ian Lefebvre

Goldin's acid-coloured depictions of tattooed love boys and drag queens from the 1980s, punks and lovers, drug-fuelled parties and domestic abuse, for instance, are very inside, diaristic, in fact. It's her world (louche, romantic, low-rent boho) and we're welcome to it. Winogrand, by contrast, seems very much Emerson's transparent, walking eyeball – the avid witness at once in the thick of it and at a remove. The 100-plus Winogrands in the Zacks are almost too much to take in on one visit, so rich are their encyclopedic contents, compositional complexity and intuitional acuity. Was there an event, be it a demonstration, political convention, dress ball, Central Park Be-In or visit to Mount Rushmore, that Winogrand didn't capture in his 1960s heyday – and almost always in an unpredictable way? No wonder he died, too soon, in 1984, reportedly leaving more than 5,000 rolls of film undeveloped!

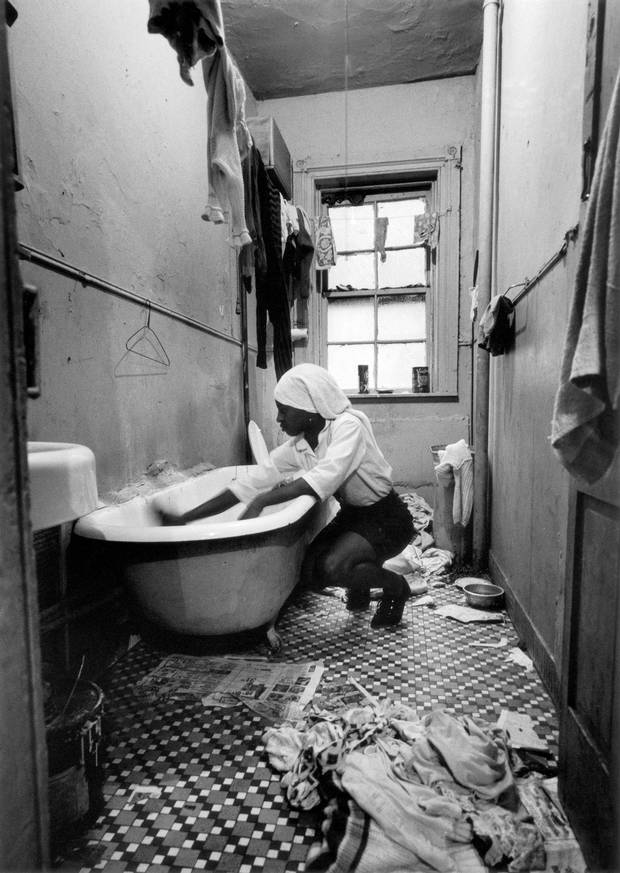

Parks occupies an interesting position on the insider/outsider continuum. He's represented here by the series of photographs he took in the fall of 1967 of a destitute African-American family living in a Harlem tenement. In his mid-50s at the time, Parks was on assignment for Life where, in 1948, he'd been named the famous weekly's first-ever African-American staff photographer. Parks's pictures of (and complementary text about) Norman and Bessie Fontenelle and their eight children, which appeared over 16 pages in a March 6, 1968, special edition published one month before the Martin Luther King assassination, make for a powerful, gritty essay. And clearly Parks, as a black man raised in poverty himself, brought an existential and ethical authority to the assignment that another photographer (i.e., a white one) might have lacked. (Indeed, Parks reportedly befriended his subjects well before he started to photograph them.)

Nan Goldin’s 1973 Picnic on the Esplanade, Boston.

Nan Goldin, 2016

At the same time, the contemporary viewer likely will feel uneasy flipping through the copies of the special edition that the AGO has provided as a complement to the Parks presentation. Life, after all, was a very white magazine back then, its affluent audience keenly courted by advertisers. So as much as the Parks essay may resonate with the current plight of African-Americans, it's hard today not to see it as an exercise, however earnest, in ghetto tourism and liberal guilt-tripping, and to ponder Parks's implication in that. A similar feeling also attends the watching of Diary of a Harlem Family, a 20-minute PBS documentary, also on view at the AGO, that Parks subsequently made and narrated, using stills from the Life project. It is, for the most part, such an unremitting portrayal of desperate poverty that it comes close to being a parody of that poverty, a Deteriorata rather than a Desiderata, more a call to give up than an incitement to anger.

No doubt it's the 55-plus Arbus portraits, positioned pretty much at Outsiders's halfway point, that will draw the largest crowds. Almost 45 years after her suicide in New York, her fame and artistic stature remain unassailable – a condition Outsiders not only affirms but heightens, thanks to the superb prints lent by a group of Toronto collectors. While the works are largely familiar, featuring plenty of "greatest hits" – yes, Virginia, there's Identical Twins, Rochelle, N.J. from 1966 and 1962's Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park – they're refreshed by the company in which they're being shown. (Lest we forget, it was Winogrand and fellow street photographer Lee Friedlander with whom Arbus was teamed for the epochal New Documents show in 1967 at the Museum of Modern Art. Moreover, in the AGO's Winogrand gallery, there's a 1969 portrait of Arbus hard at work at a Love-In in Central Park, a flower clenched in her mouth, Rolleiflex draped over her neck.)

Gordon Parks’s 1967 Rosie Fontenelle Cleans the Bathtub.

The Gordon Parks Foundation

Today we think of Arbus as the intense, uncompromising, painfully deliberate chronicler of nudists, giants, albino sword-swallowers, overweight girls and freaks (of the latter she famously said: "[They] were born with their trauma. They've already passed their test in life. They're aristocrats."). But we tend to forget that many of Arbus's most famous portraits were done not purely out of self-interest or to elevate the self-esteem of her subjects but as fodder for mass-circulation magazines. Indeed, several of the portraits in the AGO show – including those of Jack (The Marked Man) Dracula (he of the 308 tattoos), Tiny Tim, James Brown (in curlers) and Charles Atlas – first appeared in magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post, Esquire, Holiday and Harper's Bazaar.

Danny Lyon's 25 black-and-white photographs are positioned near the exhibition's exit, adjacent, fittingly, to the Nan Goldin space. (The Goldin site also presents a 42-minute slide show of images, published and unpublished, from Goldin's famous 1986 book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency; the 400 slides are soundtracked to songs by the Velvet Underground, Bronski Beat and Charles Aznavour, among many, many others.) Fittingly because Lyon's pictures are, with Goldin's, the most diaristic in the exhibition, capturing scenes of his time in the early sixties when this university philosophy graduate and son of an ophthamologist (Alfred Stieglitz was one of his patients) was a member of the Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club.

Garry Winogrand‘s 1969 Richard Nixon.

The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Near the Lyon and Goldin showcases is what could be called a homage to the old family snapshot – you know, those 3-by-4 centimetre prints, often in watery colour, shot with a Brownie camera, the rolls dropped off at the neighbourhood drug store. Except here the roughly 200 photos displayed in vitrines aren't of Mom and Dad hosting a party in the rumpus room or of Junior enroute to Cub camp, they're of male cross-dressers who, in the 1950s and early sixties, would travel to Casa Susanna, a rather rundown resort in upstate New York where they could don dresses and wigs with impunity. The AGO first presented a selection of these photos in 2014, lensed by fellow, mostly unidentified cross-dressers (insiders shooting outsiders, in other words), to mark Toronto's hosting of WorldPride. This led the gallery last year to purchase 340 Casa pictures held in a single collection. The relaxed artlessness of the Casa Susanna pictures makes them, in their fashion, the coziest, "straightest," most familial part of Outsiders.

There's much else to see and ponder in Outsiders, including looped screenings of Kenneth Anger's 1963 biker/homoerotic fantasia Scorpio Rising and Pull My Daisy (1959), a 28-minute shaggy-dog story starring such Beat Generation luminaries as Allen Ginsberg, Larry Rivers and Gregory Corso, rigorously co-directed by the legendary Robert Frank (of The Americans fame), with Jack Kerouac providing an appropriately Joycean narrative spew. Indeed, there were times when I felt there was too much of a muchness. But always I'd find something to keep me going – the punctum in Arbus's portrait of sixties topless dancer Carol Doda gently but matter-of-factly raising the silicone swell of her bared breast with her left index finger; the swoony elegance of A couple kissing on stage, 1963, again by Arbus. Furthermore, I was "helped" by the sheer intelligence and beauty of the exhibition's layout. One sterling example: The walls of the Zacks Pavilion have been painted a matte white (the only exception being, I think, the matte grey used in the Arbus section). As a result, the gelatin silver prints have a zing, a sheen, that's almost shimmery. You're pulled toward the light.

No doubt some visitors will come to the exhibition wondering why their "favourite" outsiders have not been included. Where are Stephen Shore's pictures of Andy Warhol and his Factory denizens? Gene Anthony's 1965-67 portfolio of the hippies of San Francisco? Larry Clark's dope-shooting, gun-toting reprobates? Stephen Shames's Black Panthers? Me, I left with eyes and mind full and satisfied, the exhibition's parts satisfyingly representative of the entire outside(r) world(s). The biggest photo show since the AGO reopened in 2008, it's one of the year's must-sees.

Outsiders: American Photography and Film, 1950s-1980s is at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, through May 29. There are related lectures at the gallery's Baillie Court and a series of films at Jackman Hall during the run. Details at ago.net/outsiders.