A Toronto-based art historian's detective work uncovered a treasure trove from one of the Dutch artist's most productive periods. On Tuesday, the public gets to see those works for the first time in a new book. James Adams took a peek

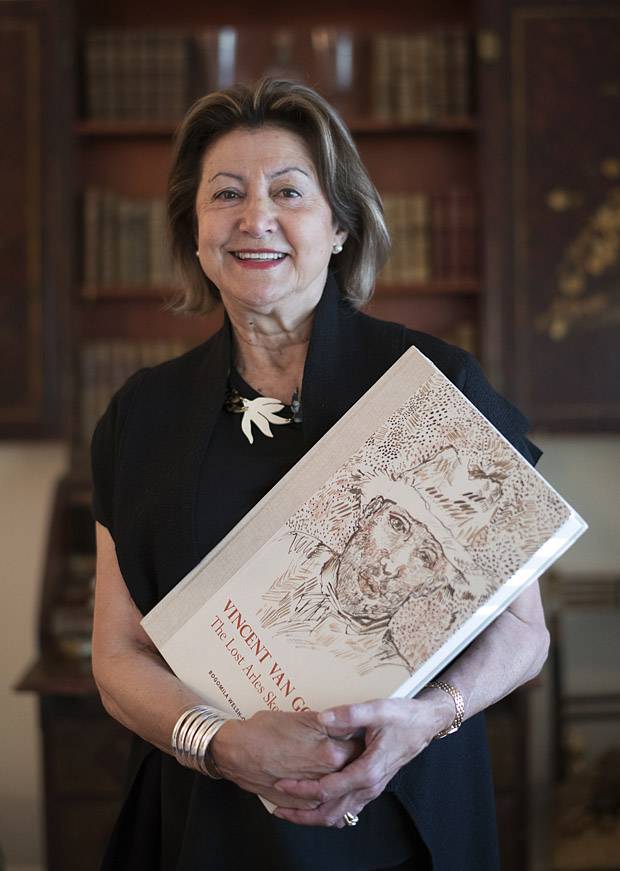

Dr. Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov has had a long and passionate attachment to the Provence region of southeastern France. Since 1992 the vivacious art scholar and historian, Bulgarian-born, Toronto-based, has spent pretty much every summer in the same charming rental property just west of Aix-en-Provence.

It's the beauty of the place and the many friends she's made there that keep drawing her and her husband, William Lerner, back – "not necessarily," she stressed in a recent interview, "being close to van Gogh." To suggest such a closeness to the world's most famous painter, though, is not without foundation.

At 77, Welsh-Ovcharov is an internationally renowned authority on the art and life of Vincent van Gogh. And it was Provence, from February, 1888, to spring 1890, where van Gogh made his provisional home, first in the town of Arles, 75 kilometres west of Aix, then, a few months after famously severing his left ear in late 1888, at the asylum outside Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, 25 km northeast of Arles.

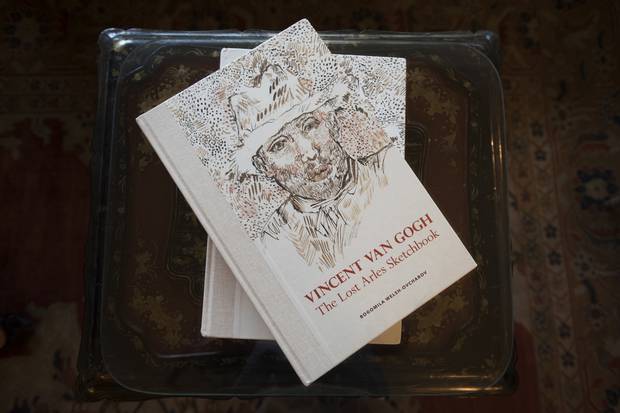

Now, if anything, the Welsh-Ovcharov/Provence/van Gogh ambit is about to get considerably tighter. On Tuesday afternoon in Paris, at a much-anticipated media conference at the Academy of Architecture, the professor emerita in art history from the University of Toronto will be unveiling the astonishing contents of her latest book, Vincent Van Gogh: The Lost Arles Sketchbook.

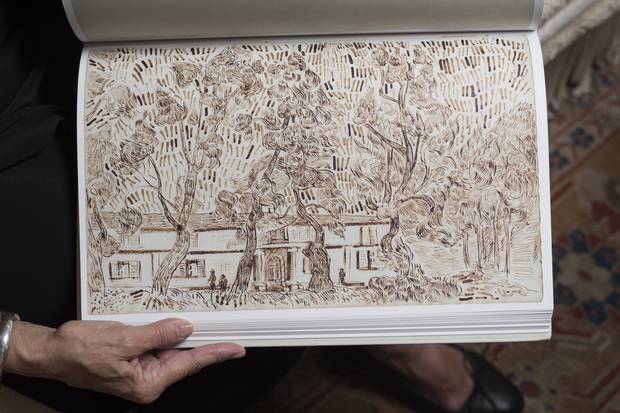

As much world-historical moment as international publishing event, the plush volume is highlighted by facsimile-sized reproductions of 65 hitherto unseen unsigned drawings done (primarily) in reed pen and brown ink by van Gogh during his tumultuous, ferociously creative years in Provence. The book is being published Tuesday simultaneously in France, Germany, the Netherlands, Britain, Canada, Japan and the United States.

The drawings, which came to Welsh-Ovcharov's attention a little more than three years ago, and now their public availability, represent nothing less than "the most revolutionary discovery in the entire history of van Gogh's oeuvre" – this according to England's Prof. Ronald Pickvance, at 85 generally regarded as the most doyen of van Gogh art doyens, writing in the book's foreword.

Security around the book, a hardcover, has been tight. While its English-language publisher, Abrams, announced its publication in June, it stressed then that "no other information" beyond its trim size (an oversized 38.3 by 25.1 centimetres), page count (288) and price ($105) would be disclosed until the Nov. 15 media conference. As part of a signed embargo agreement, The Globe and Mail recently was permitted to spend several hours with the finished book at its Canadian distributor's office, take notes and then, a few days afterward, to interview Welsh-Ovcharov.

There are seven van Gogh sketchbooks already "in the world." There may have been more but these are the surviving ones. All are housed in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and cover the artist's time in the 1880s in Nuenen (the Netherlands), Antwerp (Belgium), Paris and, finally, Auvers-sur-Oise, the village northwest of Paris to which van Gogh decamped in May, 1890, and where he died two months later, age 37.

Van Gogh scholars like Pickvance and Welsh-Ovcharov have long believed there had to have been at least one other sketchbook, this from the painter's Arles/Saint-Rémy period – a period, often deemed the apex of the artist's career, that saw him feverishly produce some of his most famous works – Starry Night over the Rhône, seven sunflower still lifes, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe, Irises and Vincent's Bedroom in Arles, among them.

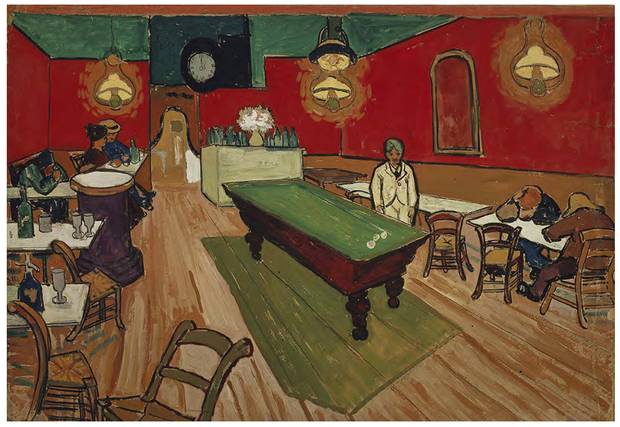

Vincent Van Gogh’s Arles period included works like The Night Cafe (September, 1888; pencil, watercolour and gouache) …

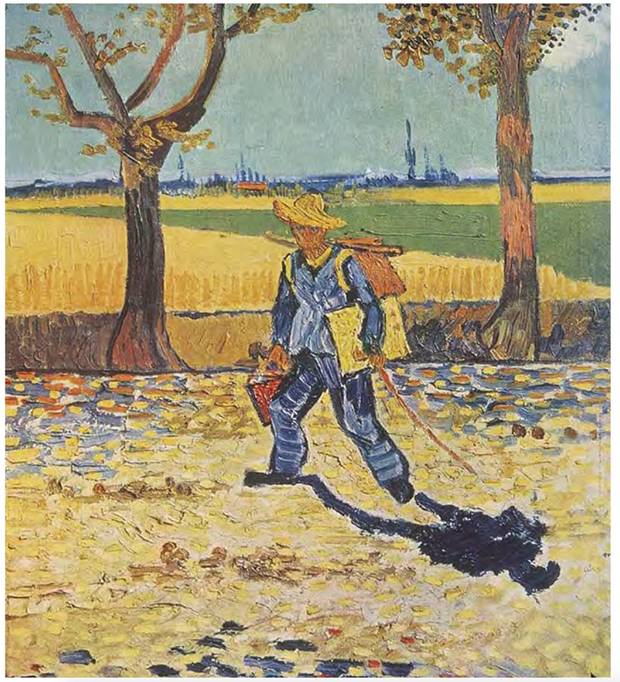

… and The Painter on the Road to Tarascan (July 1888, oil on canvas).

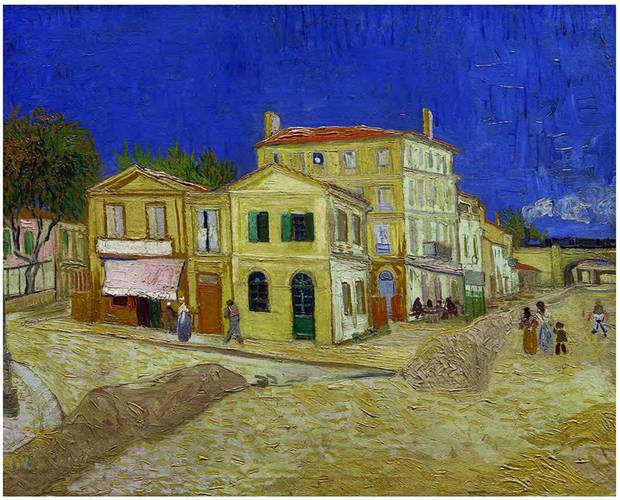

But where was that book? Had it perhaps been destroyed when Allied bombers struck German-occupied Arles in summer 1944, including an attack that destroyed the famous Yellow House van Gogh occupied with fellow painter Paul Gauguin for nine acrimonious weeks in the fall of 1888?

The Yellow House (The Street), an oil-on-canvas work from October, 1888.

Or was it extant but now a mould-covered artifact squirrelled away in a never-visited attic? The hope was, if such a sketchbook did exist, let it exist in Provence because "in Provence, people never throw anything away," said Welsh-Ovcharov.

The answer – or at least part of the answer – came in August, 2013, with a phone call to Welsh-Ovcharov at her place near Aix-en-Provence. A female friend was on the line. She'd recently met this couple in Aix; he was Franck Baille, an author of art books, among other occupations, she was Chantal Beauvois, an art historian and gemologist. They'd been tasked by the unidentified owner of a large ledger ( brouillard) of drawings – it included 10 human portraits plus pictures of farmers' fields, boats, bridges, cypress, olive, poplar and almond trees, houses – to find out whatever they could about them. The owner, a woman, had apparently received the ledger as a birthday present from her mother in 1964, its contents then put away in a cupboard and largely forgotten.

Baille thought the ledger drawings looked like van Goghs but, as Welsh-Ovcharov told The Globe and Mail, "no one was able to say anything for certain. He was in limbo." Her friend encouraged Baille and Beauvois to show the sketches to the Canadian van Gogh maven who, conveniently enough, was mere minutes away by car from the Baille-Beauvois residence. Intrigued, Welsh-Ovcharov said she'd drive to Aix with her husband and a friend to examine the ledger drawings.

It was hardly the first time Welsh-Ovcharov had had the opportunity to pass judgment or at least offer an opinion on a work or works allegedly by van Gogh. In a career spanning more than 45 years, she's mounted acclaimed exhibitions, prepared numerous books, catalogues and articles, taught generations of graduate students, lectured internationally on the artist – and been something of a sleuth, too. In 1971, for instance, she corrected the attribution to van Gogh of a painting by a leading van Gogh studies expert, proving it was, in fact, by a van Gogh contemporary, French artist Charles Angrand. Eight years later, while visiting the descendants of Albert Aurier, the French art critic who was an early champion of van Gogh, she discovered "hanging behind a door" a painting she went on to attribute, correctly, to van Gogh. Perhaps most famously she vigorously researched, then staunchly vouched for the authenticity, as a van Gogh, of the Yasuda sunflower painting, named after the Japanese insurance company that paid $40-million (U.S.) for it in 1987, the highest sum ever paid for a work of art at that time.

Walking into the Baille-Beauvois residence, Welsh-Ovcharov was led to the ledger. Since virtually all the drawings were loose, that is torn from and unattached to the ledger's binding, she was easily able to pull out, at random, a single sketch. It was of a slender, solitary cypress tree quivering against a radiant setting sun.

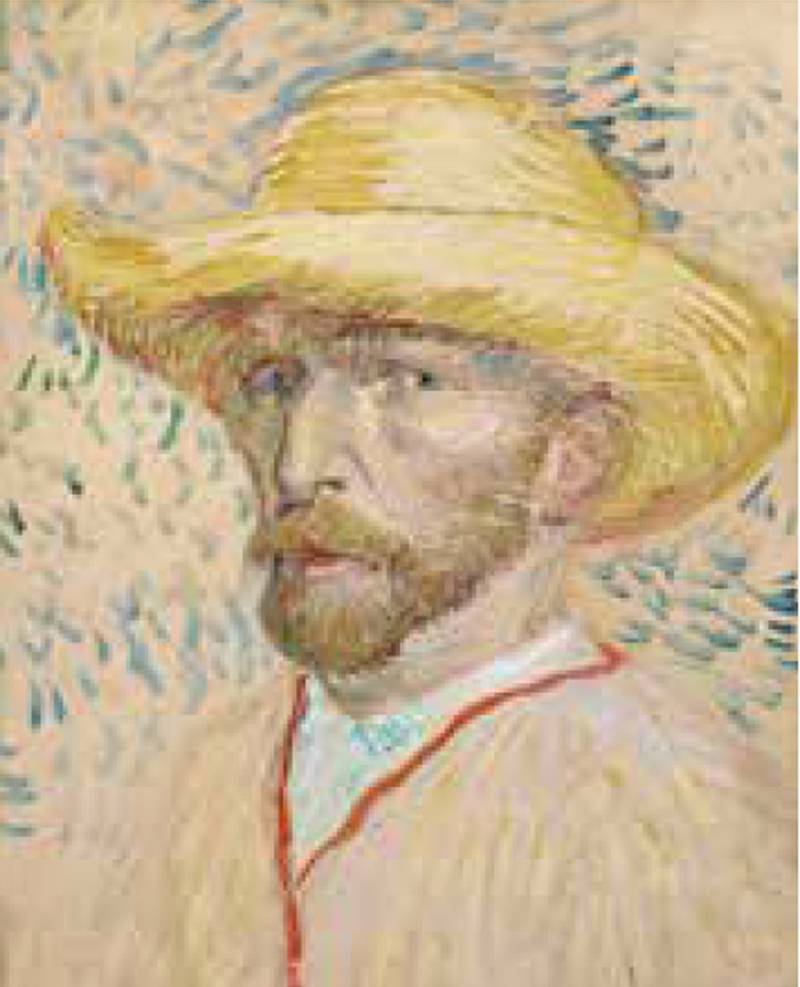

"Shocked, almost indignant," the scholar then began to leaf through the rest of the cache. One drawing was a full-face portrait of a semi-bearded man wearing a battered straw hat. Both his ears were intact. "I had to step back a little bit," she told The Globe and Mail. Yes, these were in van Gogh's hand. For perhaps a moment she thought they might be forgeries, exceptional forgeries, clever forgeries … but, no, all her training, her experience, her connoisseurship convinced her otherwise.

Three years of exhaustive and exhausting research later, she hasn't changed her mind. "Of course, you're terrified all of a sudden," she said recalling that fateful, hot afternoon in August. "To find 65 drawings! Not five, not 10 but 65.… Well, I had an omigod moment."

Welsh-Ovcharov said she was keen on "writing up something right away" but felt she needed Ronald Pickvance's counsel. She first sent him "very fine reproductions" of each of the 65 drawings. Then, with the permission of the drawings' owner and Baille, she carried 12 original drawings and a small 19th-century notebook (carnet) found with the ledger (see sidebar below) to him in England.

"He immediately got it. He looked at the drawings. He said: 'Oh, oh, Bogomila.… You've got to publish this! Get the book out before I die! Get the book out!'"

![Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov on the legacy this book leaves behind: ‘Scholars will have to look at [the drawings]. They will have to form their own opinion.… I leave it to them.’](https://www.theglobeandmail.com/ece-images/a1f/news/article32836311.ece/BINARY/w620/vangogh-main4.jpg)

Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov on the legacy this book leaves behind: ‘Scholars will have to look at [the drawings]. They will have to form their own opinion.… I leave it to them.’

FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The day The Globe and Mail interviewed Welsh-Ovcharov, the book was still a couple of weeks away from getting out to the public and she was feeling rather philosophic about what might follow. "Scholars will have to look at [the drawings]," she said. "They will have to form their own opinion.… I leave it to them."

But … would the drawings be sold en masse or singly? Donated to the Van Gogh Museum or Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum? Taken on an international tour? Examined at an international symposium? Would the owner make herself known?

She didn't know. "I'm just going with the flow.… Half of me is, 'I've done it and I've sort of finished it.' It's so overwhelming that I'm sort of deadened by it.

"Then," she observed, brightening somewhat, "I start relooking at them and I'm astonished all over again."

AN ART MYSTERY

How did the lost sketchbook get from then to now?

FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

"Circuitous" is Dr. Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov's preferred term to describe the journey of the van Gogh sketchbook. Drawing on Welsh-Ovcharov's own scholarship, new and old, as well as that of other scholars, plus the 1970 van Gogh catalogue raisonné, the painter's own voluminous correspondence, informed conjecture and, most important of all, information in a newly discovered carnet (small record book) for an Arles café frequented by van Gogh, the narrative can be unspooled thus:

Sometime between March and early May, 1888, van Gogh is given the brouillard by Joseph and Marie Ginoux, proprietors of the Café de la Gare and owners of a few adjacent properties in Arles. The artist has grown close to the childless couple. He rents a room at their café for nearly five months before moving into the nearby Yellow House in September, 1888, and maintains warm relations thereafter. (Indeed, 15 van Gogh paintings were in the possession of the Ginouxs at the time of his death.) The brouillard, filled with blank white sheets, is for business record-keeping. But new ledger books, with rules and grids, are better suited to modern commercial practices so the Ginouxs give van Gogh the plain ledger for his artistic purposes. Van Gogh draws in the book through spring 1890 – it includes a pre-mutilation full-face portrait from summer 1888 – when, after a year in the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, he leaves for Paris. Before he does, he asks his friend and physician, Félix Rey, to return the ledger to the couple. It's now full of drawings, including two portraits of Joseph Ginoux and one of Marie. Rey does so on May 20, 1890 – a fact duly noted by a Ginoux employee writing in the Café de la Gare's carnet. He describes the ledger and its contents as a "grand carnet de dessins." (All 26 surviving entries of the carnet are reproduced in The Lost Arles Sketchbook.)

No other reference to the ledger is found in any other document. From here, the brouillard may simply have been chucked into some darkened corner, joining piles of other business documents, and forgotten. Joseph Ginoux, meanwhile, dies in 1902, Marie in 1911. A niece, also childless, inherits Marie Ginoux's possessions, including presumably the ledger and the carnet, and holds them until her death in 1927. In 1930, a Marseilles businessman, Gaspard Basso, and his wife take over the Yellow House, turning it and an adjacent grocery into a café. One of Basso's sons marries a local woman named Charlotte. Charlotte has a sister who regularly visits the Basso café and household.

Welsh-Ovcharov's research leads her to the daughter of the sister. She indicates to the historian that the sketchbook and the carnet were somehow uncovered by the Allied destruction of the Yellow House and other structures in 1944, then recovered by her mother. The sister, very possibly the first person to actually look at the drawings in more than a half-century, "likes what she sees." But "knowing nothing about art, and with no artistic education," she gives the material to the daughter for her 20th birthday and she – unnamed by Welsh-Ovcharov, her city of residence unspecified as well – continues to own it to this day.

ART CRITICISM

What do the drawings 'say' about van Gogh's art?

A patron looks at a Van Gogh self-portrait at Montreal’s Museum of Fine Arts in 2014.

RYAN REMIORZ/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Fans of Vincent van Gogh shouldn't approach The Lost Arles Sketchbook thinking they're going to find, say, either a full-blown preparatory drawing or prototype for The Starry Night. Rather, says Dr. Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, it's more about "drawings as first ideas, or things he was mulling through and quickly putting down."

"You see a very private van Gogh here, van Gogh as a personal draftsman … creating for his eyes only," she continues, rather than making sketches of completed paintings to show his brother, the art dealer Theo van Gogh, or highly finished drawings to woo the interest of wealthy Australian artist John Russell. That said, there are several "virtually finished works" in the ledger, the most outstanding perhaps being Pine Trees in the Asylum, dated to October, 1889.

It's true, says Welsh-Ovcharov, that you can locate in the lost Arles sketches tropes and flourishes that would surface in paintings. For instance, the nebula-like cloud whorl in the sketch Welsh-Ovcharov calls Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the background (late spring 1889) makes two appearances, in the skies of The Olive Trees and The Starry Night, both painted around the same time.

The book also is a fascinating showcase of van Gogh's stylistic means, the rudiments of his artistic vocabulary – dots, dashes, sinuous lines, cross-hatching, patterning, confetti-like sprinkles – and a celebration of his mastery of the humble reed pen.

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Illustrator Matt James on the fine line between creation and destruction

2:16