Speaking recently at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Thomas Ruff said he used to “really believe that photography captured reality.”

This would have been when Ruff was in his early 20s – he’s 58 now – and deeply under the spell of his teachers, Bernd and Hilla Becher, at the Dusseldorf Art Academy. The Bechers, husband and wife, were famous for their straight-on, rigorously composed black-and-white photographs of 20th-century industrial “types” – the water tower, the grain silo, the blast furnace, the coal mine tipple, the storage tank. For the Bechers, this systematic approach demonstrated what photography did better than any other medium while combatting “the gooey and sentimental subjectivist aesthetics” that photography too often embraced.

Come the late eighties, though, and with the onset of digital photographic technology, Ruff grew miffed that “reality did not look as I wanted it to look.” His ambition was to produce “an ideal photo,” not “the great and authentic reproduction.” Let the Walker Evanses of the world do that. If a parked car or a large tree was somehow compromising the particular view of a building Ruff was determined to photograph, he no longer considered waiting for the car to be moved or striding to another vantage point. Thanks to the miracles of Photoshop and other digital manipulations, what offended the eye could be plucked from the image, banished to the electronic ether.

Since then, Ruff has become less and less interested in whatever truth claims photography may have, and more and more famous internationally as a result. For him, photography is a playground, a realm/reality unto itself, with an ever-expanding array of processes and potentials that are as interesting as the images they produce (and sometimes more so). Today, he likes to call his lens-based work “investigations,” as in: “I make investigations that ask people to become aware of what they’re looking at.”

You can find that credo stencilled on the wall near the entrance to Thomas Ruff: Object Relations, now up in all its gorgeously austere conceptualist glory at the AGO. Billed as Ruff’s first major solo Canadian museum exhibition, it features some 40 works from five series the artist has undertaken using photographic prints and negatives not of his own making, but ones he’s found and/or collected and subsequently manipulated or been inspired by. Among the inspirations at the AGO: two large, arresting photograms – camera-less images created by placing objects on photographic paper and exposing them to light from an enlarger – by U.S. experimentalist Arthur Siegel made in the 1940s; two electrocardiograms of frogs, taken in 1909; an eye-zapping study of an electric spark photographed in 1885 by E. L. Trouvelot.

One of Object Relations’ series is a world premiere. Called press++, this work-in-progress consists of Ruff digitally mashing onto a single plane the image of a discarded press photograph with the caption, date-stamps and other markings found on the photo’s reverse, then presenting the pentimento-like montage as an oversized chromogenic print. The four examples at the AGO are of military/aerospace themes, the most immediately striking being a 223-by-185-centimetre print of U.S. astronaut Ed White’s historic 1965 walk in space. (The heavens remain of deep interest to Ruff, who told an audience at the AGO that he “would have gone to Heidelberg to study astronomy” had he not been accepted into the photography program at Dusseldorf in 1977.)

press++ is a complement to an earlier series, Zeitungsfotos (newspaper photographs), that saw Ruff, between 1981 and 1991, collect more than 2,500 images from German-language newspapers and weeklies that struck his fancy. After removing the cutlines from these newsprint photos, he tossed them all into a big box which he then closed. Opening the box a decade later, he discovered he “could not remember the context” of the photos; the collection “had no meaning.” He proceeded to re-photograph the clippings, doubling their original size so as to more clearly reveal the images’ halftone dots.

Object Relations has 24 of these re-photographs displayed in two vitrines. Unsurprisingly, the absence of captions tests the viewer’s memory and knowledge – Who’s that dead guy? Rodin? Matisse? Why were Leonid Brezhnev and Richard Nixon sitting on that park bench? Is that a picture of a falcon or a hawk? Einstein: one wife or two? – at the same time it prods the viewer to create narratives, inferences and commonalities (fictions, in other words) solely on the available visual evidence. Zeitungsfotos, too, is a sobering reminder of the eclipse of the heyday of print photojournalism, before pixels supplanted dots, when newspapers and magazines had a near-monopoly on the manufacture of the image-world and the mass dissemination of that world.

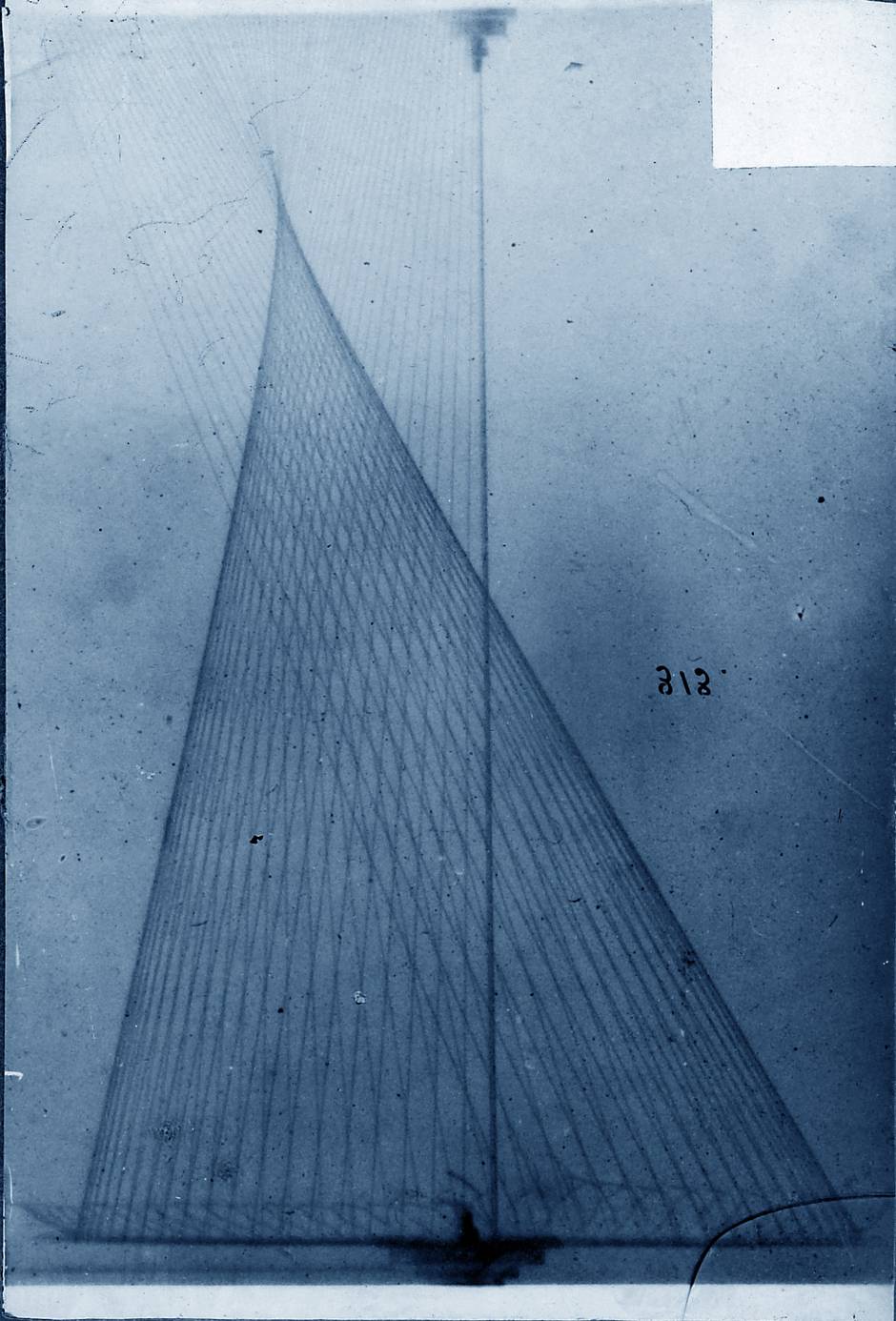

Object Relations, in short, is a very historical show in terms of both its tangible stuffiness and the content embedded in the stuff. Hanging on the walls surrounding Zeitungsfotos are examples from two other series, Maschinen (2003) and Sterne (1989-92). The former comprises seven large, hand-coloured prints made from glass negatives prepared in the 1930s for a catalogue illustrating a Dusseldorf company’s industrial wares. Back in the day, the depicted machines no doubt seemed the very emblems of modernity. But in Ruff’s “hands,” all those thrusting screws, steel wheels and hulking forms now look like so many Rube Goldberg contraptions or discarded props from Fernand Léger’s Ballet Mécanique or models for The Killing Machine, a creepy 2007 installation by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller. At the same time, who can’t see Maschinen’s inventory as a sort of homage to the persistence of the Bechers in the Ruff’s aesthetic?

Meanwhile, Sterne (meaning stars) features four framed prints, all large and deeply vertical, all derived from images of the night skies originally published by the European Southern Observatory in Chile. Fittingly combining his photographic and astronomical interests, the series marked the first time Ruff worked with extant rather than self-generated materials. So not only is Sterne the oldest series historically in Object Relations, it’s the oldest cosmically when you realize its photos are of galaxies millions of light years away.

Time – it keeps slipping into the future even as the past is always present.

Thomas Ruff: Object Relations, curated by AGO associate curator of photography Sophie Hackett, is part of Toronto’s 2016 Contact Photography Festival. It is at the gallery through July 31.