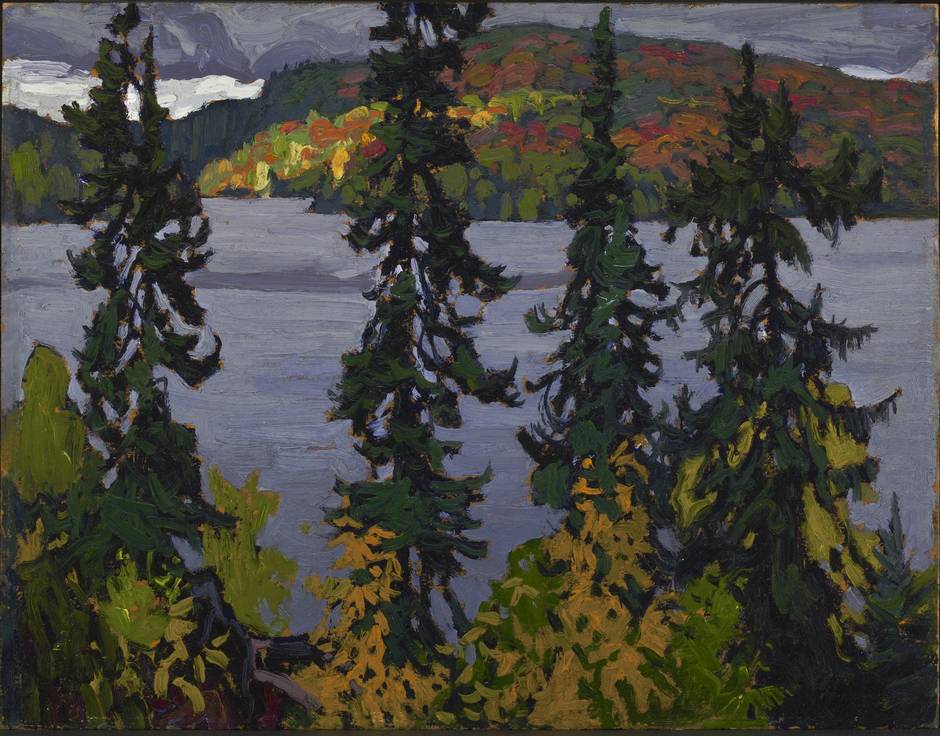

You gotta start somewhere with somethin’. For Robert and Signe McMichael, that fateful conjunction of place and object occurred in 1955 when they paid $250 to the Roberts Gallery in Toronto for an oil sketch on paperboard by Lawren Harris. An autumn landscape done in 1920, the year Harris founded the Group of Seven, Montreal River was all of 27 centimetres by 35. Small, in other words, but very striking.

And perfect, too, for the McMichaels’ recently completed home, an impressive log-beam-and-fieldstone house with an audacious south-facing floor-to-ceiling window fronting an ample living room with an equally ample stone fireplace. It was located about 40 kilometres northwest of Toronto on a four-hectare parcel that the McMichaels, married, childless and in their early 30s, had bought in 1952 near this quaint former farming community atop the meandering Humber River valley.

The Harris purchase marked the start of a mania for Canadian-art collecting by the couple, most especially art by Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven. And as that collection expanded, so did the house: Over the next 18 years no fewer than four additions, each designed by the original architect, Toronto modernist Leo Venchiarutti, were built, in 1963, 1967, 1969 and 1972.

But the key date in all this is Thursday, Nov. 18, 1965. On that day, the McMichaels and Ontario’s Conservative government of the day signed an agreement that resulted in the donation to the province of the McMichaels’ 14-room home, their art collection, the adjacent land and a shack previously occupied by Thomson in Toronto’s Rosedale Ravine that Robert McMichael had moved earlier to Kleinburg. (The McMichaels, in return, were allowed to live on-site, with all expenses paid, exercise a high degree of curatorial control and occupy two of the five seats on the new board of trustees. They also received permission to be buried on the property. When it was no longer tenable for the McMichaels to live on-site, the Ontario government built them a $300,000 home in nearby Belfountain.)

It’s this donation, totalling 194 paintings, hyped at the time as “the single largest private collection of Group of Seven paintings,” that formed the basis of what was then called the McMichael Conservation Collection of Art, now the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. And it’s this donation that’s being celebrated right now in a lovely anniversary show at the McMichael smartly titled A Foundation for Fifty Years. Curated by Sarah Stanners, the McMichael’s brainy new director of curatorial and collections, the exhibition features 24 paintings, Montreal River among them, from that original donation and from friends and acquaintances of the McMichaels who subsequently got caught up in their vision of “a distinctively Canadian sanctuary that could be enjoyed by all.”

That enjoyment wasn’t actually fulfilled until July 8, 1966, when the Collection officially opened to the public after a few months of renovations. The debut wasn’t entirely a jaw-dropping revelation as the McMichaels had been showing their collection over the years to visitors on an invitation basis. In 1964 alone, in fact, more than 11,000 patrons had made the drive to Tapawingo, the name the McMichaels were now calling their property, derived, allegedly, from the Anishinaabe – or was it Haida? – word for “place of joy.” Still, the Collection proved a draw: For each of the next few years, more than 200,000 paid their respects as the venue became a day-trip staple for school children in central and southwestern Ontario. Attendance never regained – and has never regained – those lofty heights after the centre closed in 1981 for a two-year, $10.4-million renovation. For 2013-14, the McMichael reported just more than 111,000 visitors – but student attendance remains strong, around 30,000 a year.

What’s sometimes forgotten in the legend of Robert and Signe McMichael is how late they were to the blue-chip Canadian-art-collecting game. By 1955, the Group of Seven had been disbanded for almost a quarter-century. Lawren Harris was 70, A.Y. Jackson 73; J.E.H. MacDonald, David Milne, Emily Carr and Franz Johnston were all dead. Big, important canvases such as Frederick Varley’s Stormy Weather, Georgian Bay (1921), and Thomson’s The West Wind (1917), The Jack Pine (1916-17) and Northern River (1915) had gone into public collections such as the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario) decades earlier. Meanwhile, Painters Eleven, those rowdy abstractionists from Toronto, had been rocking the contemporary scene for almost two years.

As a result, for some, the McMichael smacked of the anachronistic while the collection itself, certainly for its first 15 or 20 years, was decidedly patchwork – heavy on sketches, short on easel paintings, not a single J.W. Morrice landscape in sight, an assemblage pulled together from gifts, bequests and the canny cajoling and deal-making of Robert McMichael. In 1986, the Toronto Star called him “Toronto’s most successful bargain-hunter,” noting his knack for getting an Arthur Lismer here for $200, a Franklin Carmichael there for $75. He also befriended artists: Jackson spent his last six years living at Tapawingo as “artist-in-residence”; A.J. Casson and his wife, Margaret, were regular visitors, often “babysitting” the house when Robert and Signe travelled. Moreover, no fewer than five of the original Group are buried on the gallery’s grounds, the first interred being Lismer, 83, in 1969. Grounds that, as Stanners points out, were “virtually a blank slate of mostly farmland” when the McMichaels first appeared, then artfully and systemically were reforested to resemble the boreal terrain the Group so loved to paint.

Today, 12 years after Robert’s burial in that same hallowed grove, eight after Signe’s, the McMichael has filled many of its gaps – of the 300 or so sketches attributed to Tom Thomson, for example, the McMichael owns a respectable 91 – to build a collection totalling 6,000 works, including an impressive inventory of aboriginal art.

It hasn’t been easy. Few cultural organizations in Canada have had a history as fraught as the McMichael, a history marked by court challenges, legislative amendments and huge churns in staffing as well as accusations of political interference, disputes over direction, threats of purges to its collection and considerable bad blood. Since much of this has been reported in the media in the past 40 years, little needs to be added at this time. Except to say, perhaps, that had the McMichaels not been so fiercely attached to what they had wrought – what the couple liked to call “the original vision” – the Collection’s protracted transition to a professionally administered, publicly funded Crown corporation, with a curatorship committed to honouring the past and recognizing the present, would have gone a lot more smoothly.

A Foundation for Fifty Years is a sensitive reflection of that vision and the McMichael’s first iteration. With the exception of Jackson’s desolate First Snow, Algoma (1920), a sort of First World War scene transmogrified into a Canadian Shield landscape, the works are small to medium-sized, straightforwardly hung at eye-level on a rich grey fabric background. As you might expect, there are the usual suspects – five Harrises, three Thomsons, a Varley, two Carrs – but one particularly surprising selection is Yvonne McKague Housser’s Marguerite Pilot of Deep River (1932). Surprising because it’s a portrait by a woman of a strong-looking woman of Aboriginal and French descent, painted very much “in the key” of one of Gauguin’s Tahiti canvases. Stanners, it seems, could easily have put a Johnston or Carmichael winter landscape in the Housser “slot” (neither Group of Seven original is in the show) yet chose instead to invoke other idioms, other narratives.

A Foundation for Fifty Years runs through Nov. 18, 2016, at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ont. Other exhibitions and programs marking the 50th anniversary of the Collection opening to the public will be presented in 2016.