In comparing ourselves with Americans, Canadians usually fall into two camps. One views our neighbours to the south as being very much like ourselves, more similar than different – once, of course, you strip away those differences of politics, health care, education, historical development and the like. The other camp, by contrast, sees these differences as utterly crucial to national self-identification. And not only are Canadians different, we’re better.

A new book of photographs puts these notions gently and often charmingly to the test. Called The Canadians, it’s the first release from Bone Idle Books, a recently created division of the Archive of Modern Conflict established in the early 1990s by David Thomson, chair of Thomson Reuters Corp. and The Globe and Mail.

If by chance its title rings a bell, well … that chiming is no hallucination. The Canadians is a sort of riff on or reimagining of Robert Frank’s canonical The Americans, first published in France in 1958, then in the United States a year later and now regarded as “arguably the most significant book in the entire history of photography,” to quote the distinguished Canadian art writer Robert Enright.

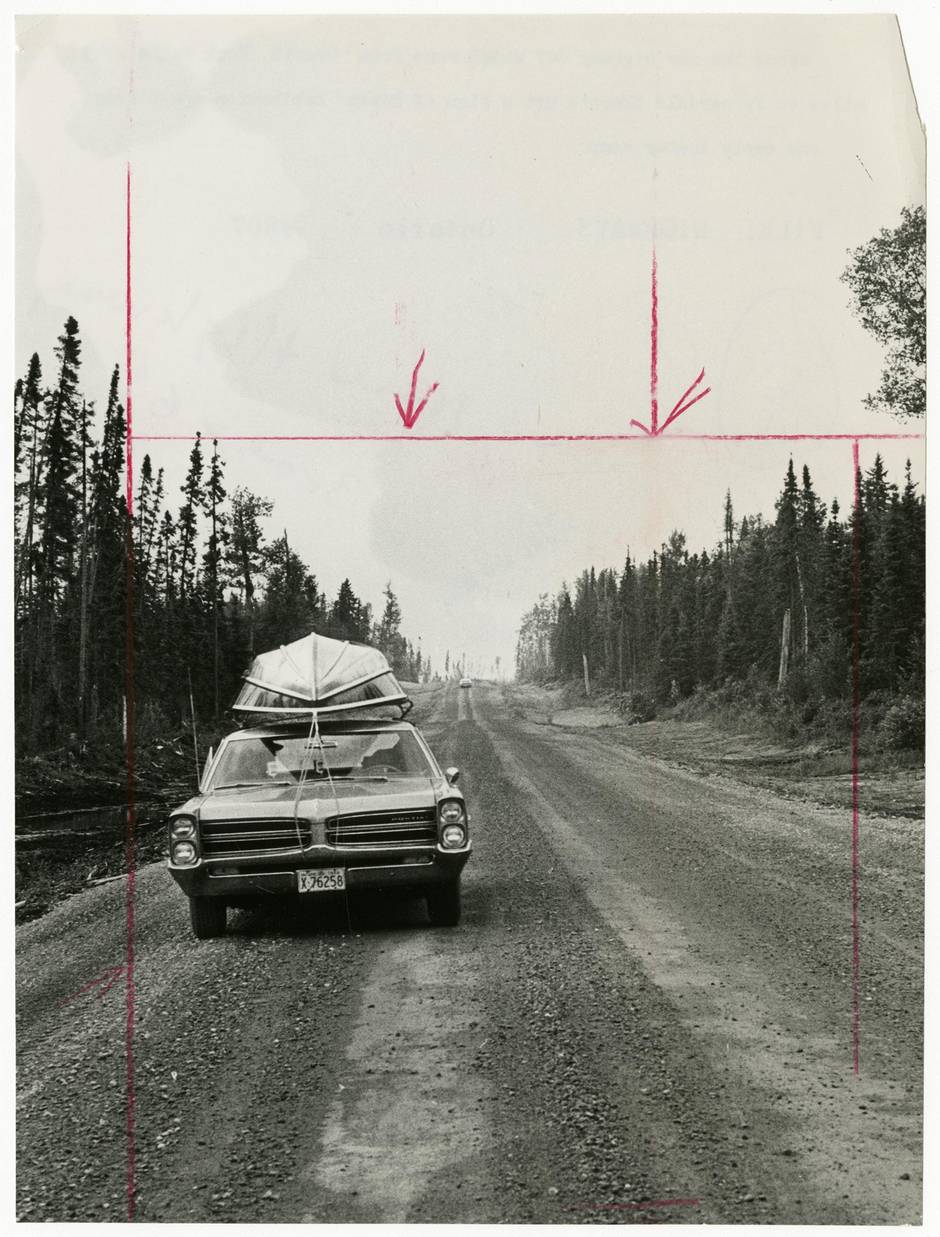

To get the 83 black-and-white images in The Americans, Frank, who came to North America from Switzerland in 1947, spent a total of nine or 10 months driving 16,000 kilometres across 30 states, locking in more than 25,000 pictures onto 767 rolls of film. In the end, what he created was a new American iconography, of stars and bars, forever roads and TV sets, drive-ins, jukeboxes, crosses, cars and motorcycles – what Jack Kerouac, in his famous introduction to The Americans’ 1959 edition, called “a sad poem [sucked] right out of America onto film, [with Frank] taking rank among the tragic poets of the world.”

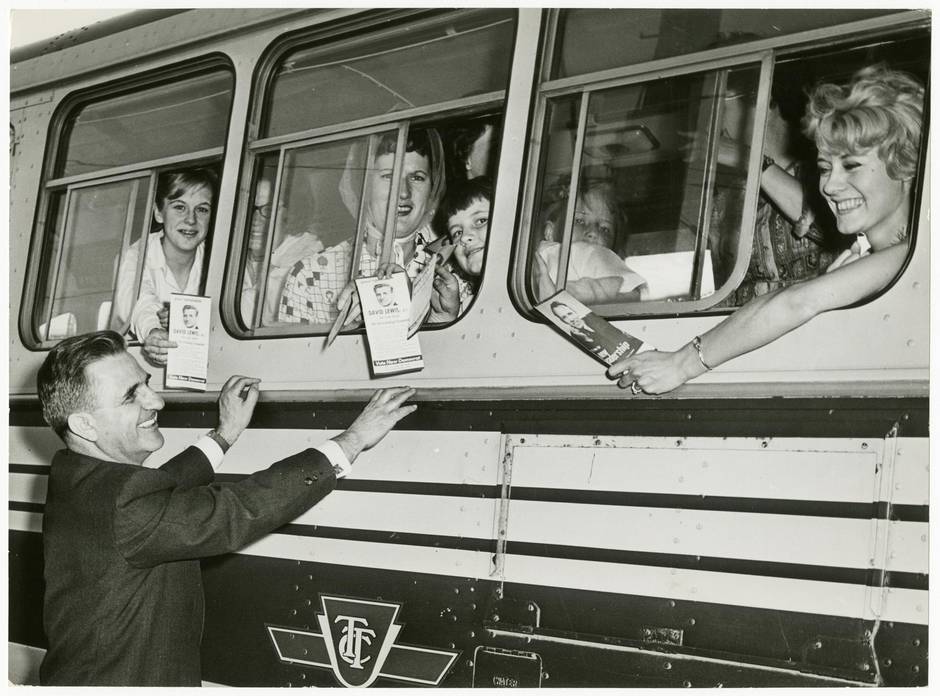

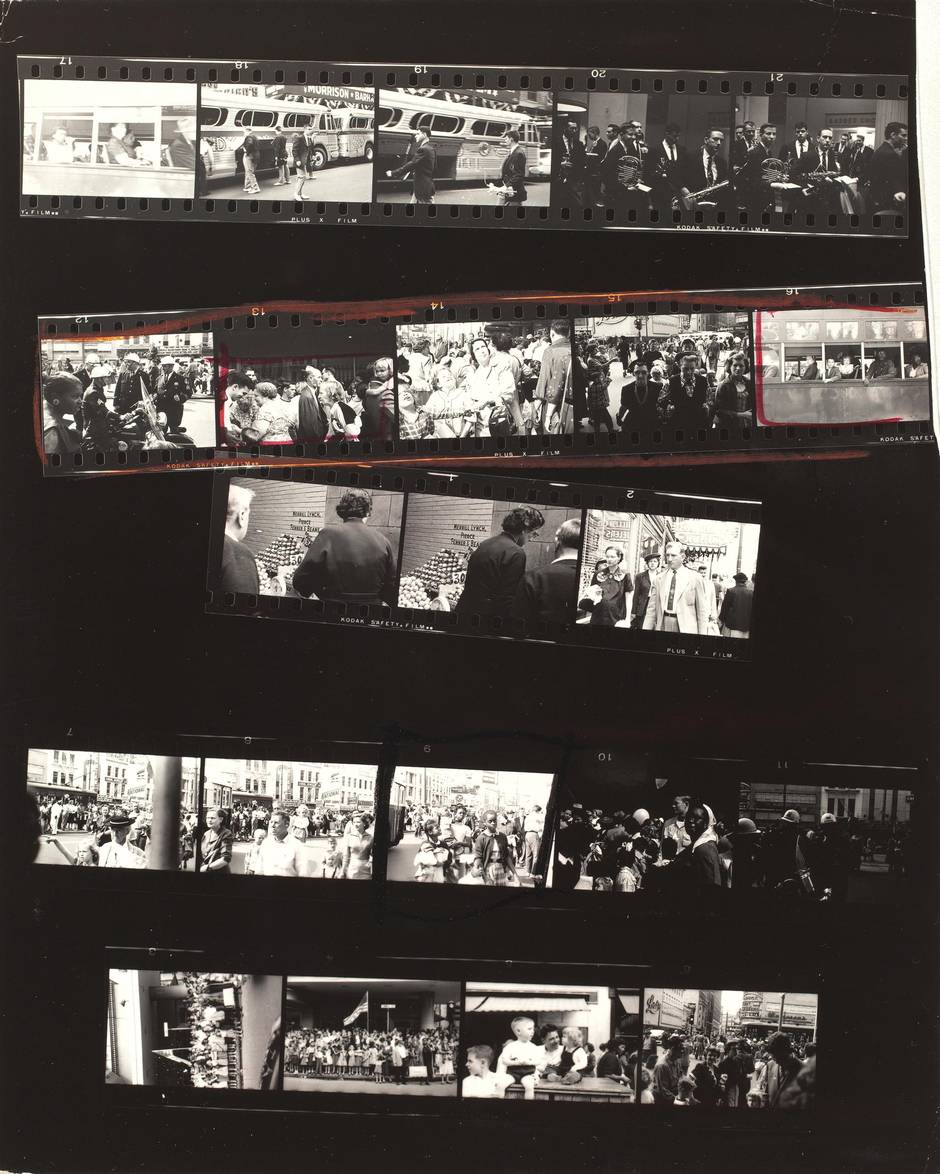

No one, I think, is going to wax quite as eloquent as Enright or Kerouac about The Canadians. To get its 79 black-and-white images, its creators – veteran British photography curator Roger Hargreaves and two Toronto associates, Jill Offenbeck and Stefanie Petrilli – pored over the 20,000 photographs from The Globe and Mail print archives that are soon to be housed in the Canadian Photography Institute in Ottawa.

Hargreaves and crew initially weren’t using the photographs in The Americans as a kind of medium to assess, organize and choose the Canadian content they were seeing. Their concern, in fact, was to find 200 or so pictures to divide into what eventually were 12 “narrative categories” for display in an exhibition for the 2016 Contact Photography Festival in Toronto. (Called Cutline, the exhibition ran April 30 through late June in the former press room of The Globe and Mail.)

It’s important to remember that the prints the trio were perusing weren’t conceived nor seen nor used as autonomous art works. Created under often onerous deadlines, their primary function was to illustrate news stories laid out on the tightly formatted pages of the daily Globe.

Nevertheless, over time, the three curators would observe how some of these all-Canadian images appeared more, well … artful than others. One day, Hargreaves came across a picture that made him think: “Wow, that looks an exact doppelganger for one of Robert Frank’s images.” Soon he was seeing “another and another and another” and soon they all were “looking back through The Americans over and over again.”

When Cutline opened, it included a sidecar exhibition of their finds, titled The Canadians – 28 prints in the “key” of Robert Frank, framed against a maple-leaf red background. In the meantime, plans were afoot for both a national tour and a Canadians book.

Genre-wise, The Canadians might best be described as a parody of The Americans, albeit minus the ridicule or broad comic effect associated with the term. Certainly its trim size, look and overall presentation echo The Americans, but, interestingly, there’s not a single written reference to it anywhere, neither in the characteristically perceptive and funny introduction by Douglas Coupland (who was born two years after The Americans’ U.S. publication and eight before Kerouac’s death) nor on the dust jacket and flaps (which are, in fact, a blank white).

This seems to presume that would-be buyers either are aware of the photographic spectre haunting The Canadians or, if they’re not, the book is sufficiently attractive on its own merits as not to require any verbal tipoff. (To my eyes, The Canadians is best appreciated with The Americans nearby, as Canadians are to Americans in the real world.)

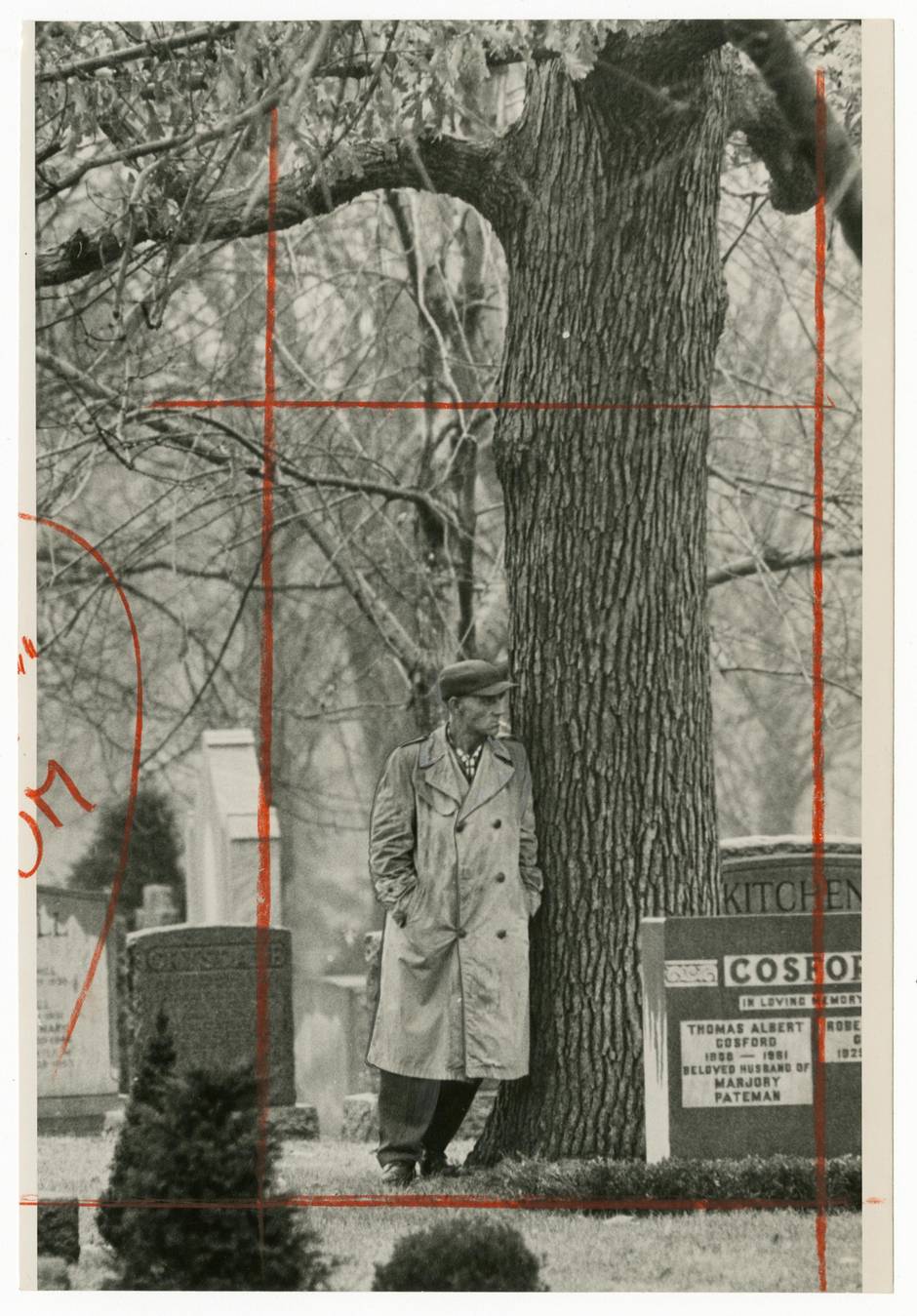

Most of the pictures in The Canadians date to the 1950s and ’60s, although there are 12 or 13 from other eras, most prominently the 1970s. This isn’t a quibble as it’s clear that the book’s creators and designer Lauren Wickware wanted a particular aesthetic, not a historically accurate overlap with The Americans. Yet overlaps there are – of theme, print texture, objects, character, composition, mood, gesture.

Note how, in a 1967 Fred Ross photo, the position of Ottawa mayor Charlotte Whitton’s arms and body almost match that of the visitor in Frank’s Yale Commencement, shot a decade earlier. Or how the blanketed form of a dead kidnap victim in Ontario in 1963 echoes the blanketed corpses in Frank’s Car Accident – Arizona. Or the contrast between the straight-to-the-horizon medians in Frank’s U.S.A. 285 and the wackily positioned lines on Toronto’s Commissioners Road. Compare, too, the five tombstone-like newspaper boxes lensed by The Globe’s Fred Lum in 1996 with the five equally tombstone-like gas pumps found in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

At the same time, there are at least two pronounced absences or disconnects.

While The Americans is chock full of pictures of black men and women, there’s not a plainly recognizable shot of an Indian anywhere in The Canadians.

Further, in the Frank, Old Glory, the Stars and Stripes, is “as common as a shadow,” to quote a Couplandism, but you’ll troll The Canadians’ pages in vain for the Maple Leaf or the Red Ensign.

An exterior shot of the Exeter, Ont., town hall from 1966 reveals a flagpole without a flag. Perhaps, as Coupland notes, this reflects the antipathy many felt toward the Maple Leaf when it was introduced in 1965: “Every person born before 1945,” he writes, “hates [it] to their grave.”

Intriguingly, for all the formal correspondences between The Canadians and The Americans, the summary impressions of each book are quite different. Frank’s America is a country of motion and menace, quiet desperation, tightly coiled energy, alienation, racial tension, doggedness. The country of The Canadians, by contrast, seems pokey, parochial, almost premodern, earnest and overwhelmingly white, not to mention white-bread. Even our biker gangs back then looked less like dangerous thugs than extras on the set of a Fabian flick.

It was a world, Coupland observes, in which “people were born, became teenagers and then, magically, at the age of 21, turned into chain-smoking 50-year-olds with undiagnosed cancers.”

The Canadians: Photographs from The Globe and Mail Archives is published by Bone Idle Books Sept. 1. The Americans remains in print. Selected images from The Canadians will be featured in a touring exhibition called Cutline, opening Oct. 21 at the new Canadian Photography Institute in the National Gallery, Ottawa.