For two more weeks, in Montreal's Old Port, you can watch a ghostly ocean liner sail most evenings across a 120-metre "screen" made from the spray of 30 fountains in the St. Lawrence. The only thing separating this apparition from the stage illusions of yesteryear is a century's worth of technology and a magician dressed in white tie and tails.

Our industries of amazement have changed, but the desire driving them has remained the same. We want to see something that seems impossible, and to wonder what made it happen.

The forerunners of Laser Quantum, the Montreal company behind the water projections in the Old Port's Montréal Avudo show, are currently displaying their skills in an exhibition at the McCord Museum. Illusions – The Art of Magic consists of dozens of huge lithographed posters from the days when pretending to saw a woman in half was a fascinating novelty, not a campy cliché.

The heroes of magic's golden age – roughly 1880 to 1930 – were tricksters, technicians, con men and entertainers. Part of what made them stars was their ability to latch onto deep popular fixations that had little to do with rabbits and hats.

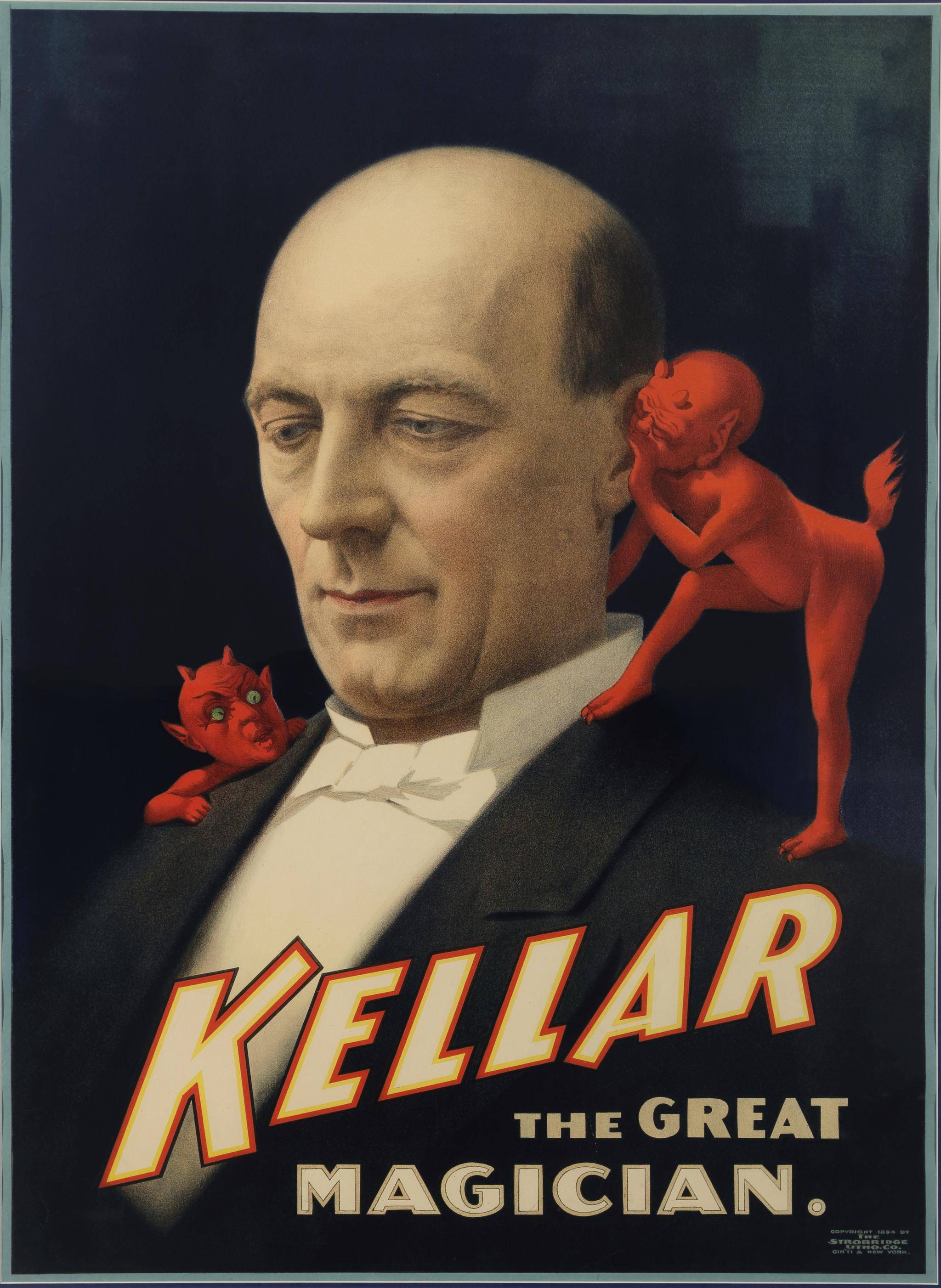

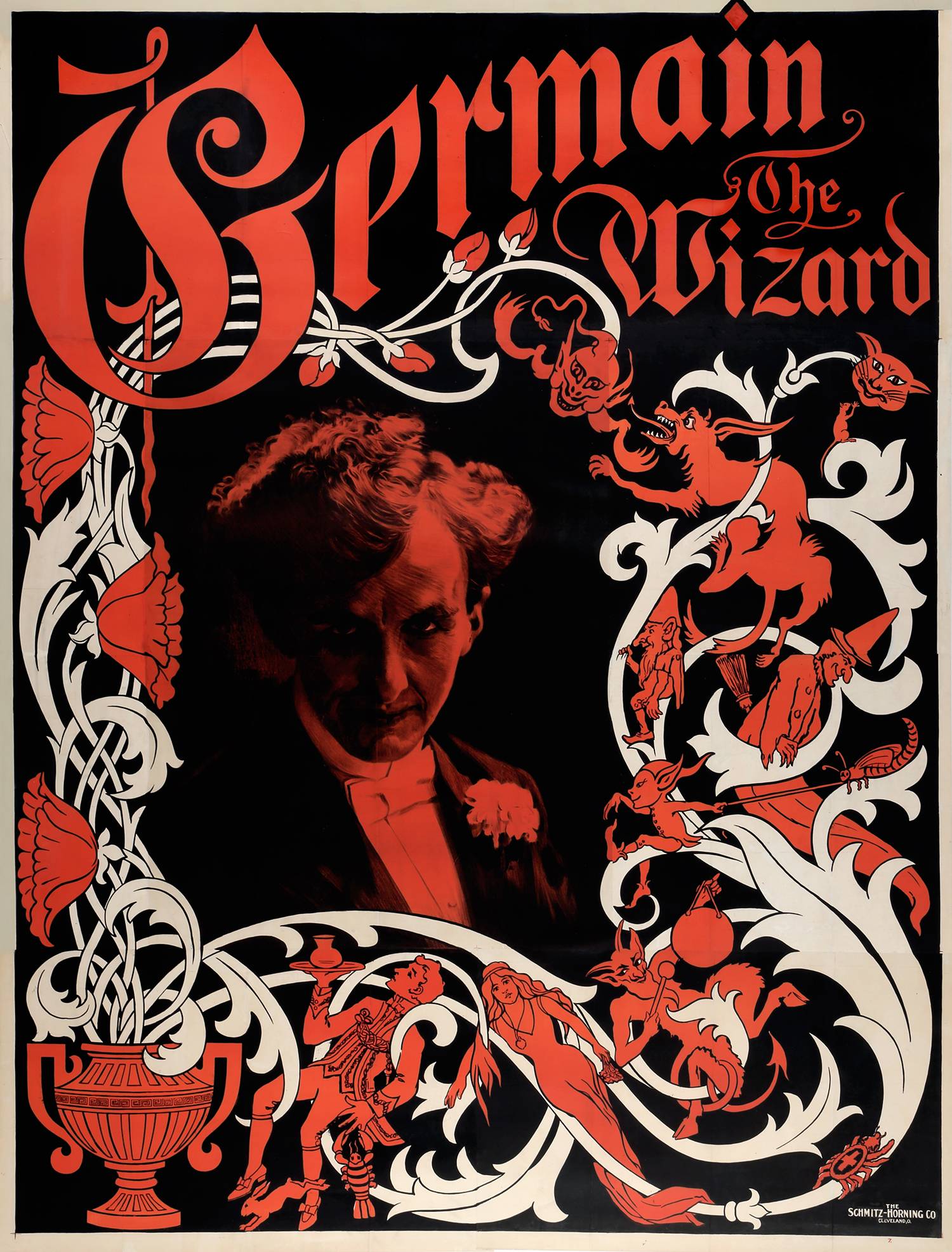

Many of McCord's pristine colourful posters – all of them from a collection donated in 2015 by broadcaster Allan Slaight – are jammed with symbols of the exotic and the paranormal.

Magic's golden age coincided with the last imperial rush by the European Great Powers, which scrambled to seize territory in Africa, Asia and the Middle East. Interest in spiritualism reached its apex at around the same time. Popular magicians capitalized on both, by representing themselves as initiates of Oriental sorcery, and mediums who could communicate with spirits.

Some of the posters in the exhibition, and in the lavish related book, show the magician levitating a woman while turbaned men bow down nearby, with minarets in the distance. One poster shows the star, in pale suit and pith helmet, being roasted by dark-skinned "desert bandits" on a cross-shaped pyre, from which we assume he will escape. These are the anonymous commercial variants of a craze brilliantly explored in Montreal two years ago, in an exhibition of Orientalist oil paintings at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

The spiritualist theme comes out via ghosts issuing from the eye sockets of skulls, disembodied hands ringing bells and questions such as Do the Spirits Come Back?

The calm, controlling magician at the centre of these posters often has little red devils hovering around him.

One man who attended the Davenport Brothers' spiritualism-themed show in Montreal in 1864 later wrote that it included things that a priest "would undoubtedly describe as acts of devilry."

The Globe in 1893 published a report of a Montreal preacher denouncing spiritualism as a fraud. The 1901 census counted 616 self-described spiritualists in Canada. But the McCord curators are silent about how Quebec's powerful Catholic clergy reacted to entertainers claiming a hotline to the spirit world.

The devil also appears in these posters, usually at the magician's side, pointing out some secret lore in a book. The implication is that a fiendish bargain has been made so the audience can be entertained.

The devil typically wears his stock costume from 19th-century opera. It's as if he had just stepped out of Charles Gounod's Faust, the most popular opera throughout magic's golden age.

As in Orientalist paintings, and in magic shows of the period, women in the McCord posters are mostly passive figures, under complete control by the magician. He floats them in the air, cuts off their heads and shoots them with arrows. Female magicians such as Adelaide Herrmann were rare, and they never chopped up men.

In her catalogue essay, University of Quebec, Montreal, art historian Ersy Contogouris argues that the physical subordination of women in magic shows expressed "generalized anxiety over women's increasing emancipation."

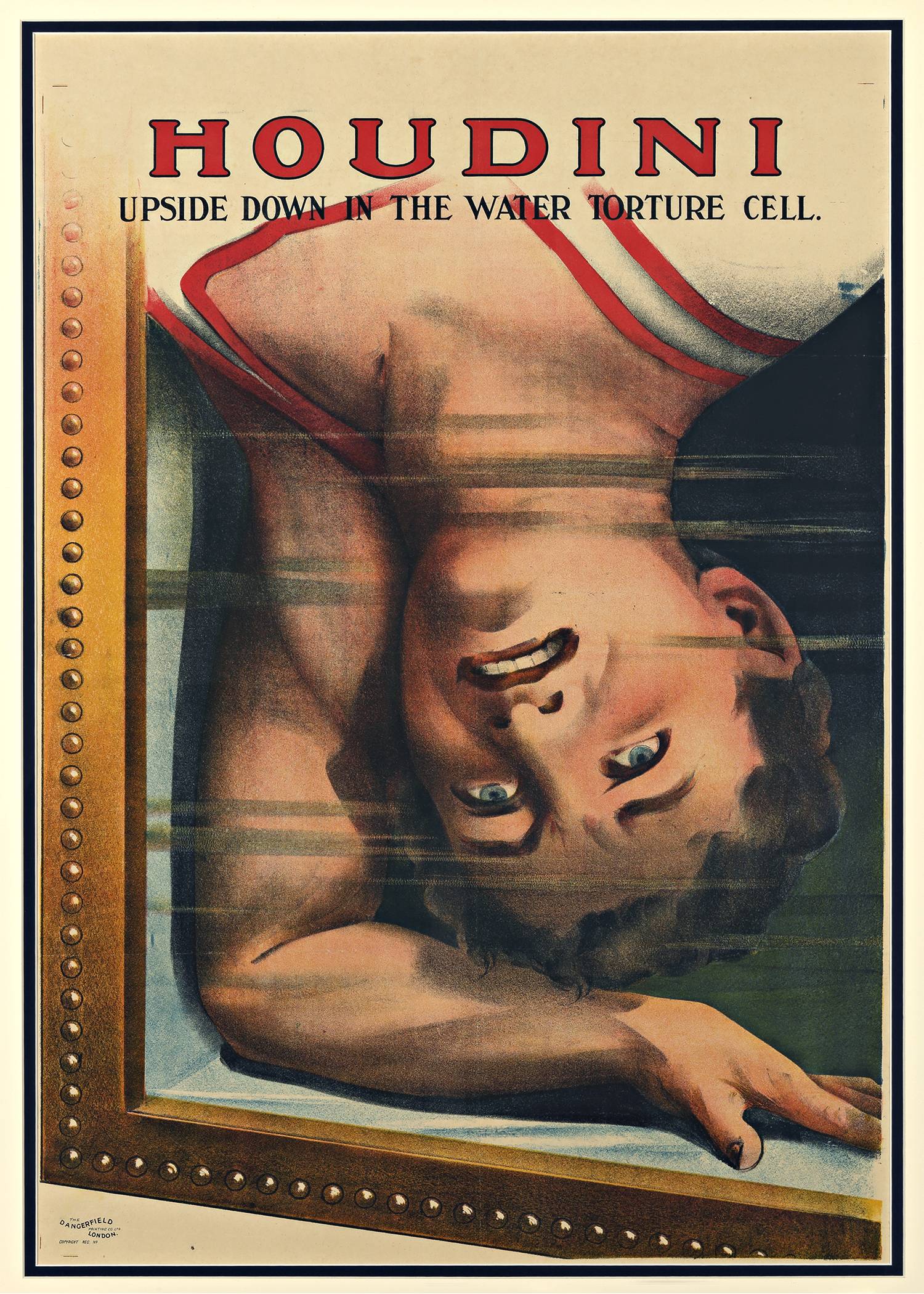

It was also part of the spectacle of pain and constraint that put Harry Houdini into locked chests, straitjackets and underwater prisons. In old-time stage magic, it was important that someone be made to suffer for the audience's pleasure.

The companies that made these enormous posters, using teams of up to 15 artisans, recycled imagery and ripped each other off freely. Their portraiture could be quite sophisticated, although subtlety was never the goal over all.

Like the performers, who invented wildly exotic backgrounds for themselves, the poster makers' jobs were to whip up a fantasy that would grab attention. The magician's first trick had to be the sale of a ticket.

The living link between classic stage magic and the luminous illusions of Laser Quantum and others was French magician Georges Méliès, who in the 1890s transferred his stage illusions to silent film, and turned a magician's theatre into the world's first cinema.

He invented many in-camera special effects, in short films that were otherwise just like excerpts from an elaborate magic show.

Méliès dematerialized the craft of magic. He also pointed the way toward the dematerialization of the magician, who no longer stares down from a poster or runs a stage show in fancy dress.

Today's magicians are mostly unknown, unseen figures. They sit in front of computers and run tests on LED systems, competing with one another to create the next new marvel in animation and lighting design.

They know what we want, and that we need to be amazed when we get it.

Montréal Avudo continues at King Edward Quay in the Old Port of Montreal through Sept. 2. Illusions – The Art of Magic continues at the McCord Museum in Montreal through Jan. 7, 2018.