After almost a year of official rumpus about Montreal's 375th birthday, the city this week celebrated a date that for many people was a lot more meaningful: The first anniversary of the death of Leonard Cohen.

It took a year to wind up to the big Cohen tribute concert at the Bell Centre on Monday and three years to prepare for A Crack in Everything, a new exhibition at the Musée d'art contemporain (MAC) that was announced before Cohen died on Nov. 7, 2016. Cohen's songs were also fêted with a mass karaoke session at the Place des Arts Métro station on Thursday and will be featured during five performances of Les Ballets Jazz de Montréal's new production Dance Me, which opens at Théatre Maisonneuve on Dec. 5.

Cohen's image now looms over the town from two gigantic open-air murals. A huge replica of one of his fedoras has been propped on the sign welcoming visitors to Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport. Silo No. 5, a monumental ruin in the Old Port, has lit up the night these past several days with gigantic projections of his words, courtesy of American artist Jenny Holzer and the MAC.

One wonders what Cohen would have made of these revels. At the media launch of A Crack in Everything, MAC director and show co-curator John Zeppetelli noted that when Cohen was approached for his blessing for the show, he said merely that he wouldn't try to stop it – and wouldn't come to the opening either.

Mortality kept the latter promise for him, unfortunately. The show has a more elegiac feeling than it might have if he were still able to skip it voluntarily. Aside from the murals, it will be the longest lasting of Montreal's current tributes and seems bound to be a hit for the MAC, less for what it shows than for the way it enables the collective fan experience.

The museum has never done an exhibition around someone whose creative output was not primarily material. Cohen published many books and albums, but these mass-produced items are not the kinds of objects museums are made to display. The MAC has satisfied its material focus by commissioning Cohen-related pieces by visual artists. What will likely make the show a popular success, however, is its use of documentary footage and its foregrounding of how Cohen's fans feel about him and his work.

Aside from the murals, A Crack in Everything will be the longest lasting of Montreal’s current tributes.

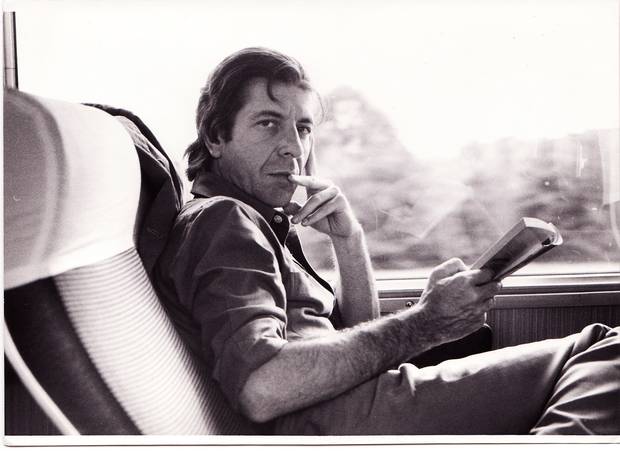

Claude Guassian

The show's largest single installation is Candice Breitz's I'm Your Man (A Portrait of Leonard Cohen). In fact, it's a ring of life-sized video portraits of 18 guys who have loved Cohen's music since the 1960s. These fans were recorded alone singing all the songs from Cohen's 1988 album I'm Your Man, with varying degrees of passion and awkwardness. Breitz has cued up their performances to create a shambling choir effect, bolstered by the actual synagogue choir of Montreal's Congregation Shaar Hashomayim, who are seen on another screen in an adjoining room.

The Montreal design collective Daily tous les jours has an installation called I Heard There Was a Secret Chord, which allows you to hear a humming chorus of Cohen's Hallelujah generated through an online portal. Several dangling microphones invite you to hum along with them.

Both these pieces are about being a fan. They act as mirrors on the performance of fanship, in Breitz's case, literally turning the camera away from the beloved and toward the devotee. Thousands of concert-goers did the same thing while taking selfies during Cohen's last tour.

The show's documentary layer also brings the fans into view, through multiscreen works by George Fok and Kara Blake. These stitch together audiovisual footage of Cohen speaking, reciting or singing, alongside shots of his fans reacting. The docs loop in immersive dark rooms with soft seating and were by far the biggest draws at the media opening. Blake and Fok make one of the same points as Breitz: That fanship is both a solitary relationship with the star and a form of collective recognition that strangers share your passion.

Most of the pieces solicited by Zeppetelli and co-curator Victor Shiffman as a visual artist's personal response to Cohen's work have less punch. This may be for the same reason that celebratory odes are seldom important poems.

For me, the most vivid original work is Clara Furey's When Even The, a solo choreography performed live each day around a sculpture by Marc Quinn, with an ambient soundtrack by Furey's brother Tomas. Furey says her piece is focused on Cohen's experience of Zen Buddhism; the 90-minute work shows her shifting slowly between poses that at various points look sculptural, meditative or carnal.

Furey gets at the opposition roiling through Cohen's work, between agitation and stillness, anguish and peace. So does filmmaker Ari Folman, whose Depression Chamber installation transfigures your own image while you hear Cohen singing Famous Blue Raincoat.

The MAC became a music producer for this show, commissioning musicians such as The National, Feist and the Montreal Symphony Orchestra to record covers of Cohen songs.

Michael Putland

The MAC became a music producer for this show, commissioning musicians such as The National, Feist and the Montreal Symphony Orchestra to record covers of Cohen songs, which play endlessly in an installation called Listening to Leonard. There will also be a series of five concerts at the Salle Gésu, during which invited musicians will run through entire Cohen albums in song order.

No composer was invited to twist Cohen's musical legacy into new shapes, although Christophe Chassol's Cuba in Cohen teases a ghostly music track from Cohen's recitation of one of his poems. Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller's The Poetry Machine uses an old Wurlitzer organ to let you randomly cut and remix his readings from Book of Longing – a music-editing procedure without music. It might have fun to hear what Christian Marclay, John Oswald or Ana Sokolovic would have made from what Cohen did with notes and song forms. I think he would have been up for more playful mischief than can be found in this show.

A Crack in Everything continues at the MAC through April 9, 2018