Not everyone would look at one of the world’s first electric chairs, a 1905 apparatus designed by Gustav Stickley for executions at New York’s Auburn State Prison, and think: “This is one of the great treasures of Toronto.”

But that’s the kind of thinking Jorn Weisbrodt has been paid to do since 2011, when he was named artistic director of Luminato, the ambitious multidisciplinary arts festival Toronto has hosted annually since 2007. Off-kilter thinking, in other words. Audacious thinking. Lateral. Provocative. And beyond a lot of thinking, the 43-year-old Hamburg-born arts administrator also has demonstrated a lot of power of persuasion, a lot of bringing things to fruition.

Which, in part, explains why visitors to this year’s Luminato will be able to see that electric chair along with 49 other Toronto “treasures,” many little-seen, little-known and often long on quirkiness, in an exhibition called Trove. Not the actual electric chair, mind you, but a photograph of it. And not just a photograph but a kind of digital construction.

These treasures, or their digital simulacra, are on view for free over the next 16 days either en masse as a site-specific installation at Luminato’s hub, the 65-year-old Hearn Generating Station in the east port lands, or as single images mounted on more than 100 billboards (digital and static), windows, storefronts, fences and vacant buildings – even an LCBO outlet and a denture clinic – scattered across Toronto. In addition, the entire project is playing in perpetual rotation on digital screens in the lobby of TIFF Bell Lightbox, with selected images in rotation at such locations as BMO Field, Air Canada Centre and the tunnel to Billy Bishop Airport.

Weisbrodt got to thinking about what is now Trove roughly a year ago. Befitting a guy who Luminato acolytes like to call “visionary,” that thinking started on a kind of cosmic level, he recalled in a recent interview, with “me musing about what are cultural institutions, really, what purposes do they serve, what audiences do they serve, what is a cultural institution for the 21st century.”

This in turn led him to a critique of the increasing specialization of museums and art galleries, and “how that has isolated audiences.” Wouldn’t it be great if “we used a public space to create an exhibition of the greatest treasures that exist in Toronto?” What if we were “to use the surfaces of the city as the most democratic art gallery that there is?”

The objects in this gallery would have to be just as democratic. Diverse, off the beaten path, not a presentation – or solely a presentation – of expected “greatest hits” such as Tom Thomson’s The West Wind from the Art Gallery of Ontario or the Glenn Gould-on-a-Bench statue outside the CBC Broadcasting Centre. Stuff, in other words, like that Stickley electric chair, which mightily impressed Weisbrodt the day he first saw it in the summer of 2011, shortly after its owner, legendary collector/dealer/ethnographer Billy Jamieson, had died. “Who knew this thing was in Toronto?” he laughed. Three years later, it was sold at auction by Waddington’s for almost $22,000 – and luckily (for Weisbrodt’s plans at least) to a Toronto collector. “It wasn’t the happiest thing,” Weisbrodt admitted, but it was unique and, in remembering it, he began to wonder what other odd but significant artifacts might be held by Toronto institutions and individuals.

Weisbrodt always saw Trove as a photographic project; the expense and time required to hunt, find, secure and relocate even 30 real artifacts would be too much and, at the same time, violate its non-hierarchical art-to-the-people ethos. The animus here wouldn’t be the systematic attempt to produce an encyclopedic survey but rather, said Weisbrodt, a reliance on “more instinctive values, like ‘What would we save in an earthquake’ or ‘What, pieced together, would paint a picture and tell a story of this city?’”

Nevertheless, Weisbrodt knew it wouldn’t be enough just to show a bunch of documentary photos, no matter how idiosyncratic their content: “I felt we needed a unified artistic voice, that the images should be works of art in themselves.”

This led him to ask Kitty Scott, the AGO’s curator of modern and contemporary art, “who that artist might be.” She unreservedly recommended Scott McFarland, whose acclaimed solo show of seamlessly constructed digital photos – Snow, Shacks, Streets, Shrubs – she’d curated in 2014.

Weisbrodt and McFarland met for an introductory conversation in early October, 2015. “There wasn’t the Hearn in the picture,” said McFarland, 40, who recalled that meeting during a recent hard-hat tour of the old power station. “There wasn’t the idea of doing a virtual gallery. Basically, there was just the idea of showing treasures in a public space, of isolated pictures for each object.”

About a month later, McFarland presented Weisbrodt with three proposals to realize the vision. One called for the creation of a virtual gallery – “a fictional space in Toronto that doesn’t exist yet.” McFarland got the idea from perusing “this mail-out from the Vancouver Art Gallery. Inside was a pamphlet about the new gallery they were designing with [Swiss architects] Herzog & de Meuron. It had all these great illustrations of what the space would look like with works from the collection.”

By this time Weisbrodt was seriously thinking of mounting much of Luminato 2016 at the gargantuan Hearn station, which, having ceased operations in the mid-1980s, was now a splendid ruin resembling nothing so much as a set for a Tarkovsky film. Weisbrodt had already announced that 2016, Luminato’s 10th anniversary, would be his last. Putting the bulk of the event in the Hearn, where, in 2014 and 2015 he’d mounted two or three one-off events, would give Luminato something to aspire to for years to come. “What,” he asked McFarland, “if we designed that new gallery space in the Hearn?”

Come late October, Weisbrodt was mailing out letters to 250 Torontonians, “basically asking them for ideas for things to include in the gallery. Did they know someone who had something interesting? Do you have anything that you would let us photograph?” Weisbrodt also took pains to mention that McFarland, a former student of and assistant to Jeff Wall, would be the digital photographer. “I thought the fact that a recognized art-world photographer was involved would appeal to recipients of the letter.”

The response, by and large, was positive and welcoming. “I think we looked at 300, 400 works of art,” famous and obscure, big and small, Weisbrodt said. “I wanted to have most of the institutions here involved and represented. So at the Royal Ontario Museum, we must have looked at 30 objects that they proposed. The same with the AGO, the same with the Aga Khan Museum and so on.” Yes, there were “two or three things we tried to get that didn’t work out” – permission to shoot Richard Serra’s outdoor concrete sculpture, Shift, being one. But over all, “we got really, really wonderful feedback.”

By mid-January, McFarland was travelling to institutions and homes, studios, lairs and storage facilities around the Greater Toronto Area to photograph treasures. And what treasures! A 1928 Felix the Cat doll owned by Moses Znaimer. World Series rings from 1992 and 1993, owned and proudly modelled by Geddy Lee. Twenty-three meteorites from Mars, in the ROM collection. A 1908 plaster cast for Brancusi’s The Kiss. The blueprint and 3-D model for the ill-fated Avro Arrow jet interceptor. The door to the home team’s dressing room at Maple Leaf Gardens. From the Toronto Public Library, Gerhard Mercator’s first map of the North Pole, published in 1595. A 1962 Chelsea boot worn by John Lennon, from the Bata Shoe Museum. A 1840 ivory-and-argillite carving of a sea captain by an unknown Haida artist, from the AGO. The costumes Rudolf Nureyev and Karen Kain wore in a 1972 performance of Sleeping Beauty. A shard from the tree, felled by a storm in 2013, that inspired the lyrics to The Maple Leaf Forever. The room containing Garrett Herman’s 170 first editions of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), plus every edition of The Times of London published between Feb. 12, 1808, and Apr. 19, 1882, respectively, Darwin’s birth and death dates.

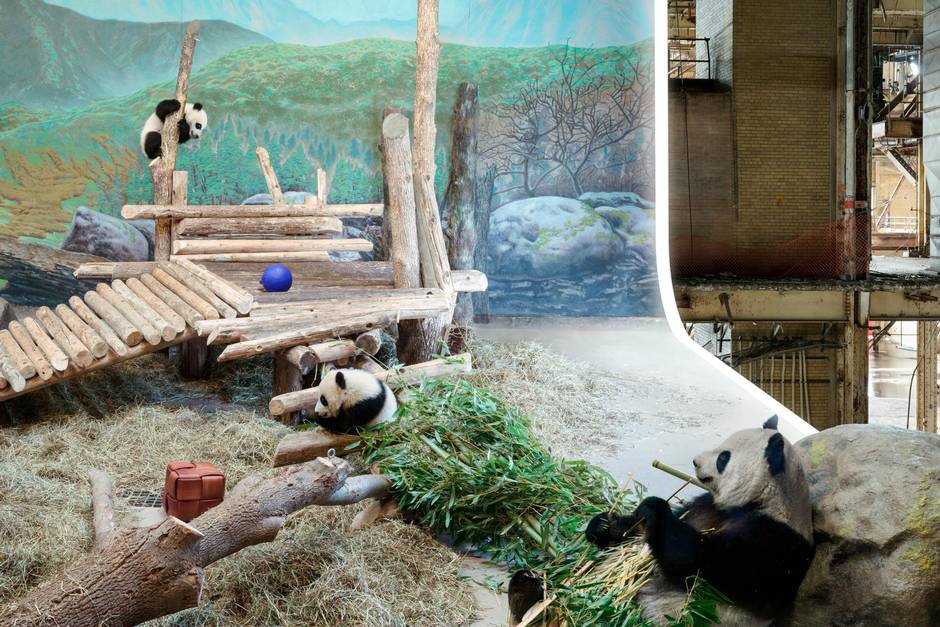

McFarland even ventured to the Toronto zoo to shoot the giant panda cubs Jia Panpan and Jia Yueyue with mother Er Shun. The bruins “weren’t hard,” he said, certainly not as difficult as lensing, say, Bruno, the taxidermied white rhinoceros at the ROM, or the Joyce Wieland quilt, Barren Ground Caribou (1978), on view at the Spadina subway station. Bruno was displayed behind glass, hence “a lot of reflection;” moreover, McFarland was allowed only a short time, sans visitors, to be with the rhino. Wieland’s quilt also was behind glass, resulting in reflections of light that “took my Photoshop assistants about five days to retouch out.”

McFarland finished photographing in late April but, as he noted, “taking pictures was just one part of a whole exercise.” He didn’t simply want to plunk pictures on a wall in the Hearn. He wanted to collaborate with Partisans, the emerging Toronto-based architecture and design firm hired by Luminato to turn the Hearn, however temporarily, into the city’s biggest cultural venue to create his virtual gallery. “It was us,” he observed, “trying to figure out to how to take these objects existing in all their different original locations and repositioning them into something more homogeneous, more specific to a group aesthetic.”

This entailed Partisans creating digitally sculptured backdrops, many perforated by apertures, that look something like the interior features of the Empire spaceships in Star Wars. Into these 3-D semblances McFarland digitally placed his treasures, sometimes just one per image, other times more in a collage-like fashion. For example, an image of Jean Arp’s Bust sylvestre (1963) in the foreground is bracketed by details from Rubens’ Massacre of the Innocents (1611) and Picasso’s Le petit déjeuner (1960), like the intrusions on one’s peripheral vision.

While each treasure gets its foreground moment, some also get supporting roles. For instance, Warhol’s tapestry of Marilyn Monroe (1968) by my count makes “a guest appearance” in at least three other images. To heighten the galleristic effect, honour the Hearn’s spatial integrity and fill in the gaps of the apertures, McFarland included photographs he took of the actual Hearn station to make triple-layered constructions.

Trove is found on the upper or mezzanine level of the Hearn’s old turbine hall, renamed Jackman Gallery for Luminato’s duration, acknowledging a donation from the Hal Jackman Foundation. There are 50 images in all, running an east-west span of more than 270 metres – enough for Weisbrodt to deem it “probably the longest columnless gallery in the world.” The 50 images, all of which are 3M laminates firmly flush to the brick wall, have been organized according to 12 loose, whimsical-seeming categories concocted by Weisbrodt and McFarland.

“Basically, we looked at the things we had, then sort of put them together. We didn’t want to create ‘The Africa Room,’ ‘The Painting Room,’ like an institution would,” said Weisbrodt. “We wanted to mix things up, so we created these surreal stories or narratives.” Thus, for example, Gallery 5 is called Bull in a China Shop and includes, among its images, a three-quarters head view of ROM’s Bruno the White Rhino collaged with an exquisite blue-and-white porcelain flask owned by ROM’s neighbour, the Gardiner Museum.

Weisbrodt acknowledged Trove’s final iteration is way more complex than he first imagined. “But you know, once you start going down a path, you have to go to the end.”

For details on Trove, click here