If you think of Vanessa Bell as the writer Virginia Woolf's sister, or as the art critic Clive Bell's wife, then a major new exhibition of her work in London, aims to re-educate you. At the centre of the wildly intellectual, frequently bisexual and artistically experimental Bloomsbury Group in London in the 1920s and 30s, Bell had an astounding artistic output herself: paintings, in styles ranging from figurative still lifes to vaguely Fauvist to abstract, including portraits of the great lights of that period. But also textiles, ceramics, drawings, graphic design and photography (including a couple of her, a usually reticent person, cavorting in the nude in her studio with her girlfriends).

Bell is usually called a minor artist: Her paintings are influenced by radical post-Impressionist European styles, but she was not a leader of change.

Usually she is called "a member of Bloomsbury" rather than singly influential, and this designation itself has not always helped her reputation, as wealthy and refined coteries make people nervous these days. The Bloomsbury Group, brilliant as it was, is never immune from accusations of dilettantism by those who think true artists must be proletarians.

Contemporary curation, however, is of course always eager to find "minor" female artists in history and reposition them in a non-sexist light, and Bell turns out to be an excellent candidate. If Bell's work is put together on its own, and not in the shadows of her friends, it shows her to be a significant and exciting artist. This new show, the largest so far dedicated solely to her, has amassed an impressing collection of these works – around 70 paintings, plus artifacts of all kinds – and makes a convincing case for her historical re-evaluation. If nothing else she was a fascinating and strong figure.

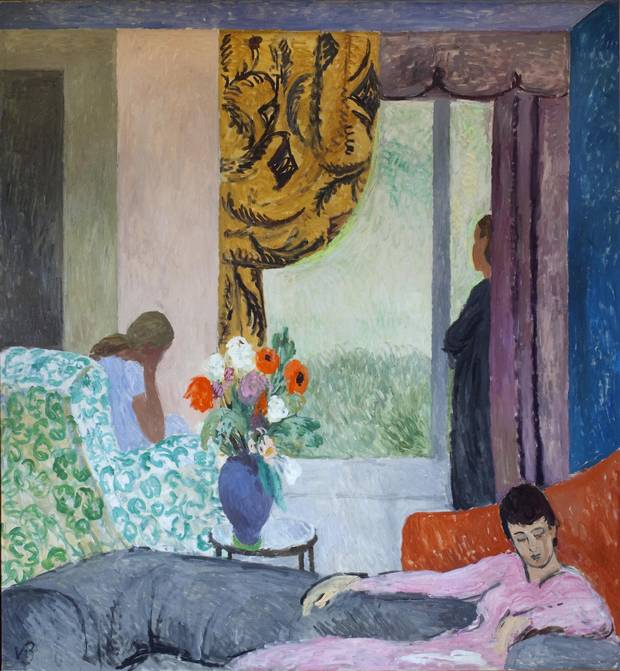

Vanessa Bell’s The Other Room – from late 1930s – offers a climpse into the artist’s astounding and frequently changing work.

…

There is a Canadian connection to this show: It was co-curated by Sarah Milroy, who is based in Ontario and used to be an art critic for this paper. The hosting gallery is the Dulwich Picture Gallery – a gorgeous setting in itself. The Regency brick, engardened Dulwich claims to be the oldest gallery in Britain, and it is not even a repurposed palace: It was designed to be an art gallery. It is a suitably snooty place in which to put the art of such marvellously privileged people.

This show, on subject matter so deeply English, in such an English place, is something of a triumph for a Canadian curator to pull off – experts on Bloomsbury are pretty thick on the ground in London and one imagines they don't give up their authority roles to colonials easily. Milroy's connection to the place goes back to her previous collaboration with her co-curator, Ian Dejardin, the director of the gallery, on an Emily Carr exhibition, in 2014-15. The Dulwich is getting quite Canadianized. (Dejardin, by the way, is the incoming new director of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Ontario.)

Bell has been celebrated in many biographies and histories of the era, and she was portrayed in several films, including Carrington (played by Janet McTeer) and The Hours (played by Miranda Richardson).

Vanessa Bell’s work, if put together on its own, shows her to be a significant and exciting artist.

Tate Images

Her painting tends to take a back seat to this biographical approach, which is not surprising, given that the sexual freedom embraced by this group is so deliciously glamorous. But they created a veritable factory of intellectual, literary and painterly production. Vanessa Bell went to art school – the Slade, the Royal Academy – and became proficient in a slick Whistlerian style, but her approach to painting was dramatically changed by a visit to Paris in 1914 where she was exposed to Picasso and Cubism.

Back in England, her work morphed into the abstract and stylized, with a gay and fearless use of colour. She took a new studio, painted the walls white and hung them with fabrics of brilliant colour. On the phone from London, curator Milroy says, "She gets permission from Picasso and Matisse to embrace colour." Her work started to look distinctly rougher, in the Fauvist style, at this point. "After Paris she went through a deliberate deskilling. It loosened her own existing impulse towards the vibrant. This was at the radical edge of British art at that time."

In the show there are many portraits of the eras' luminaries – artist Roger Fry, writer Lytton Strachey, poet Iris Tree, Mary Hutchinson (her husband's mistress), Virginia Woolf and her husband, publisher Leonard Woolf – to appeal to the historians, but Bell's portrayals are often so stylized as to be more emotional than naturalistic. Virginia Woolf's face seems to be smudged, one of Strachey's portraits gives him a face that seems to be floating apart.

A portrait of Bell’s sister, Virginia Woolf, c.1912.

National Portrait Gallery

Milroy says, "I like her commitment to freedom of expression and pleasure. I'm a chromaholic – I love colour – and there is such joy in the way she embraces colour and sensation in the world. … The word that keeps coming to my mind is ferocious: There is something ferocious about the vitality of this woman."

Does Milroy think Bell is an undervalued artist? "She has been seen as a minor artist. [Critic] Kenneth Clarke liked her work, but she has been understood to be a peripheral figure to Virginia … The most recent TV series that had her as a character – it would have been easy to watch it and not cotton on to the fact that she was an artist. It was mostly about her sexual freedom. But her freedom to break sexual conventions was linked to her freedom to break pictorial conventions. The life was lived freely, the art was made freely. The life and the art cross-pollinated."

As to whether she was less influential than those around her: "[Her husband] Clive Bell was a famous art theorist. But he respected her highly. And she was not simply imbibing his ideas – they were all arguing about these ideas until two in the morning."

As to the accusations of wealthy dilettantism that dogged her group – notably from arch-conservative and homophobe Wyndham Lewis – Milroy notes that history does not judge men and women equally on this score. "No one says Tolstoy is a lightweight because he was a count. Marcel Proust was from a fabulously wealthy Parisian family. That doesn't discredit what he did."

Landscape with Haystack, Asheham, 1912.

Smith College Museum of Art

One surprising thing about Bell's career is that she was at her most productive while raising small children. Milroy says, "She had three children – two sons and a daughter – and she was at her most experimental and avant-garde right when she was producing babies. Motherhood, and the sensuality of it, empowered her vision. A lot of women experience agency and autonomy while producing children. It can be a very clarifying experience."

Pressed to name her favourite painting in the show, Milroy chooses a portrait of an anonymous woman called The Model. "Bell was extraordinary at capturing people's physical gestures in portraits, the postures that made them." What Milroy likes about this one is a certain resistance in the model's face, perhaps captured by Bell because Bell herself (a beauty) didn't like sitting for portraits or having her photo taken.

"She's the one who looks like Princess Leia in Star Wars. She's looking away from the viewer. In Duncan Grant's portrait of the same model, she is looking more ingratiatingly at the viewer. Vanessa portrayed something unyielding and stubborn about this woman. She does not try to make herself approachable or even attractive. It strikes me that there is a kindredness with Bell about this. She looks annoyed at having her portrait painted."

Vanessa Bell 1879-1961 runs at the Dulwich Picture Gallery from now until June 4.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said Bell took a trip to Paris in 1910. It was actually 1914. Also, her husband's mistress was Mary Hutchinson, not Mary McCarthy. This is the corrected version.