On exhibit now at the Ryerson Image Centre is a collection of photos that explores the ambiguities of the business of show

The word glamour, reportedly first coined in the early 18th century, is apparently derived from the old Scottish word gramarye, meaning “magic, enchantment, delusive allurement, spell.” In other words, it’s about something exciting and compelling but finally fake, a lie – a lie that “could almost be true,” at least to the bewitched and perhaps, on occasion, even to the bewitcher.

Photography, of course, has been a major propagator of glamour. This is especially true in the 20th century, when the practice was the handmaiden at the inception of the Hollywood star system, and ever since it has given us the iconography, vocabulary and grammar – that cathexis contributing to what Freud might have called “the overvaluation of the lust object” – by which we define beauty, femininity and masculinity, sensuality and sexuality, virtue and sleaze.

Now, coterminous with the hyperventilated Hollywood award season, comes a smart, intriguing exhibition to Toronto’s Ryerson Image Centre that explores the ambiguities of the glamour enterprise, the business of show. Called Burn with Desire: Photography and Glamour, it’s been pulled together by Gaëlle Morel, RIC’s exhibitions curator, who’s drawn on an impressive range of sources, not least RIC’s own Black Star Collection and the holdings of George Eastman House in Rochester, N.Y. Besides the plethora of photographs, there’s also some judiciously selected video content.

Morel – fittingly, I think – has chosen to begin the exhibition with a section devoted entirely to Marilyn Monroe, the quintessential product (and victim) of Hollywood’s star-making machinery in the mid-20th century and, 53 years after her death, still the planet’s most enduring and instantly recognizable glamourpuss. The section’s panoply of effects serves as an introduction to the themes and motifs the curator deals with more fully in the rest of the show. So we have six of Andy Warhol’s famous, colourful, silkscreen-on-paper images of Monroe from 1967, and Richard Avedon’s large, equally famous photographic portrait of a pensive 30-year-old Monroe, all vulnerability and cleavage. There are shots of Monroe on set, on the red carpet, at leisure, plus a 21-second clip of 8-mm colour film from 1957 of Monroe arriving at a soccer stadium, perched on the back of a convertible and waving to the crowd. Watching it, you can’t help but think of another 8-mm clip that would be lensed six years in the future, namely Abraham Zapruder’s home movie of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the most glamorous U.S. president ever and, at least as the tabloids would have it, Monroe’s lover.

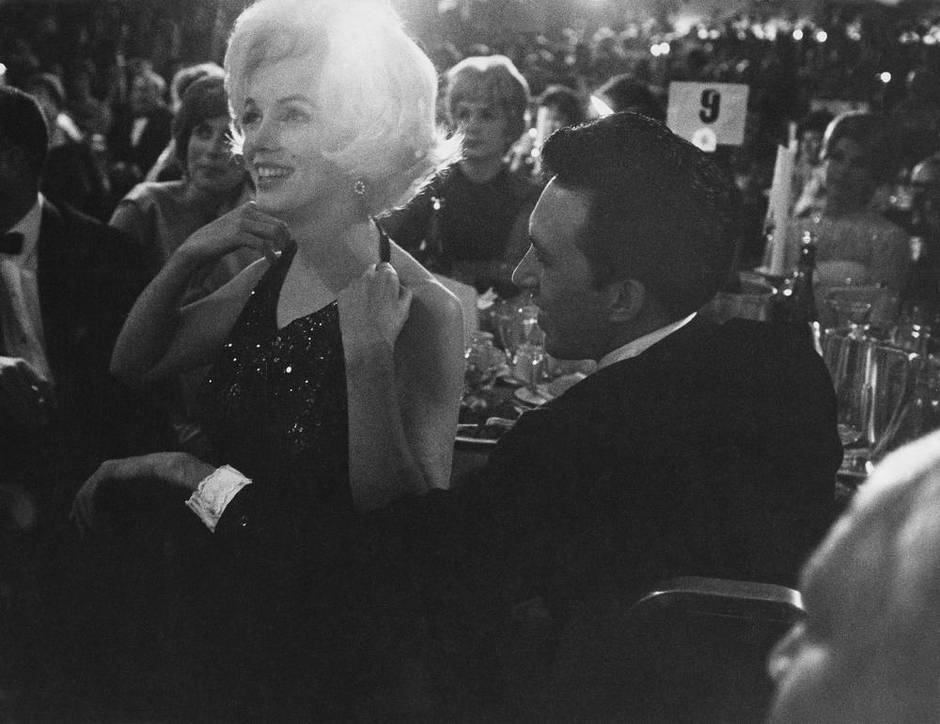

The section’s most eye-gripping element, however, is a suite of 13 black-and-white photographs, all in platinum frames, of Monroe attending the 1962 Golden Globes with alleged paramour Jose Bolanos. In none of the pictures does an ultra-peroxided, brittle-looking Marilyn, who would be dead just five months after they were taken, engage with the flash camera wielded by Black Star’s Gene Daniels. What distinguishes the prints, never before published, are their probing, predatory, La Dolce Vita quality – the photographer’s obsessive attempt to record even a faux unguarded moment at a public event and get something all the more real, and therefore glamorous, as a result.

Morel continues this suite-like conceit throughout Burn with Desire. Sometimes the pictures are organized by milieu (such as a quintet of stars-at-premiere images, highlighted by Daniels’s 1971 print of Paul Newman giving wife Joanne Woodward the smouldering eye; individual shots of Mamie Van Doren, Anita Ekberg, Greta Garbo and Ginger Rogers at the beach), sometimes according to stars (five shots by an unnamed photographer of Warren Beatty and Natalie Wood at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival; three of a standing Marlon Brando in his late-30s), sometimes by pose (a diptych of head-thrown-back-in-reverie Garbo portaits, one by Clarence Bull from 1921, the other by Ruth Louise from 1927). One wall is devoted to a tableau of the 16 triple-fold covers that Annie Leibovitz has photographed for Vanity Fair magazine’s annual Hollywood issue.

Yet as much as Burn with Desire concerns itself with the construction of glamour, it’s equally interested in its deconstruction. As the visitor moves deeper into the exhibition, the glossy portraits of Joan Crawford, Gary Cooper and Jean Harlow by such masters of light and shadow as Edward Steichen, Nickolas Muray and George Hurrell are increasingly infiltrated, as it were, by sundry art projects that variously question, lampoon and attack the tropes of glamour.

One of the first encountered is Lorna Simpson’s LA ’57-NY ’09, an assemblage of 25 black-and-white quasi-snapshots of an African-American woman (the artist herself) mimicking the cheesecake poses of Monroe, Betty Grable, Rita Hayworth and their ilk. Nan Goldin’s 1995 chromogenic print Kathleen at the Bowery Bar captures what could be called the consumptive side of glamour consumption: a weary, bleary-eyed, late-night woman in a cleavage-revealing, Pucci-style dress, a drink and a cigarette her only companions. Included, too, are five images from Cindy Sherman’s famous 1978 series Untitled Film Stills, and a 16-minute sample of Andy Warhol’s screen tests from the mid-1960s in which each subject was asked to stare without expression at a stationary 16-mm Bolex for 150 seconds, the results of which would help Warhol determine who had any innate star power.

In sum, Burn with Desire likely brings as much depth to the surfacey appeal of glamour as is humanly possible. If this absorbing exhibition makes any wrong “move,” it’s the smaller show Morel has curated to run as a sort of foil adjacent to it. In fact, there is nothing really “wrong” with Anti-Glamour: Portraits of Women. Much of the work, in photography and video by artists such as Rebecca Belmore, Marie Le Mounier and Leila Zahiri, is arresting. But the exhibition’s dedication to depicting women in all their archetype-defying diversity feels like a gilding of the lily that is Burn with Desire, a reflex action of politically correct correction to all the unblemished skin and luminous teeth in the room next door. Glamour, it seems to me, is its own best critique; moreover, the works of Goldin, Simpson, Kenneth Anger and Mickalene Thomas in Morel’s main show are already quite sufficient to the task of anti-glamour.

Burn with Desire: Photography and Glamour and Anti-Glamour: Portraits of Women is at the Ryerson Image Centre, 33 Gould St., Toronto, through Apr. 5. Admission is free.