Curating and mounting an exhibition of Arab contemporary art from the Middle East and North Africa has to be a fraught affair. After all, the region – if one can even deign to use such an encompassing term to describe what clearly are diverse societies – has long been a geopolitical and religious hot spot. Should the exhibition be a raw reflection of those tensions? Or feature art of a more disinterested and personal kind? Should it highlight the “exoticism” or “otherness” of the region’s art-making, or demonstrate affinities and congruences with the so-called “international art scene”? Link artists by adherence to a particular trend or aesthetic? Or celebrate eclecticism and individual difference?

Home Ground, an exhibition of work by 12 Arab artists, nine men, three women, now up at the Aga Khan Museum in north Toronto, answers these binaries not by excluding one option at the expense of the other but by embracing the validity of each apparent antinomy. The result, blessedly, isn’t some shallow mishmash but a smartly assembled survey whose mix of video, sculpture, installation, photography and other practices pleases both retina and cerebral cortex. It’s at the Aga Khan through early January next year.

All the art in Home Ground comes from one source, the Barjeel Art Foundation of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates (barjeel means windcatcher in Arabic). The foundation was established in 2010 by Sheikh Sultan Sooud Al-Qassemi, the 37-year-old scion of one of the UAE’s ruling families, and contains about 1,200 separate works from his personal collection, dating from 1888 to 2015. Most of the art is of contemporary or modern vintage, the foundation’s guiding principle being to help “the intellectual development of the art scene in the Arab region by building a prominent, publicly accessible art collection in the UAE.” Part of the Barjeel’s mission also is to build partnerships with other cultural institutions in the Arab world and abroad and, where possible, lend art to those institutions. Home Ground, directed by Barjeel’s chief curator Suheyla Takesh, is the foundation’s first exhibition in North America. (More than 100 works from the Barjeel are scheduled to be shown at London’s Whitechapel Gallery, in a series of four exhibitions running for almost a year starting early September, 2015.)

Al-Qassemi, known internationally for his commentary on Arab affairs in publications such as Foreign Policy, The Guardian, The Independent and The Globe and Mail, has been a serious art collector for about 15 years, concentrating on Arab work with occasional forays into Indian, Pakistani, Turkish and Iranian art. (His cousin is Sheikha Sultan Hoor bint al-Qasimi, founder of the Sharjah Art Foundation and curator of the UAE’s official entry in the 2015 Venice Biennale.) In a brief interview at the Aga Khan Museum last week, he said he sees “the art [as] an extension of my social commentary. Just like I write articles in English to try and explain Eastern points of view and all that, I feel like the arts can also play an important role. You know the cliché ‘a picture is worth 1,000 words’: It really does sometimes resonate. A lot of the work is political, and has social commentary already in it. So I feel as though we complement each other in that sense.”

At the same time, Suheyla Takesh was quick to stress that “there’s no agenda to showcase the artists in Home Ground as political artists.” Yes, she observed, “they’re operating in a certain contextual framework – you can’t get away from that – but they’re talking about experiences that a lot of people from elsewhere have experienced. … Anybody who’s travelled between geographies and has experienced situations of displacement, by choice or not, and questions of home, identity and belonging, will be able to connect. I think this is something people in Toronto will especially be able to relate to because it’s a very multicultural, cosmopolitan place and a lot of its residents are immigrants or descendants of immigrants. I certainly wouldn’t want these artists to just be perceived as some exotic thing coming out of the Middle East.”

The art, in fact, is frequently more poetic and poignant than sharply pointed. Take Mixed Water, Lebanon, Israel by the Lebanese-born mixed-media conceptualist Charbel-joseph H. Boutros. It consists of a seemingly plain glass of water propped on a white shelf positioned between two small, framed, simply drawn maps of Israel and Lebanon. The water, it turns out, is an admixture, one half Israeli mineral water (Mey Eden), the other half mineral water from a Lebanese source (Sohat). The small black nails holding up the maps also pinpoint the locations where the waters are from. Has the blending to create a new identity/entity resulted in an enhanced concoction? Or is it a contamination?

To create Responses to an Immigration Request from One Hundred and Ninety-Four Governments, Raafat Ishak, a Cairo-born artist whose family moved to Australia in 1981, sent out letters, in English, to individual governments around the world, including Canada’s, asking each what steps he should take to become a citizen. After waiting two years for responses (half replied, the remainder did not), in 2009 he began to paint, in muted oils on hard-board rectangles 30 by 21 centimetres, abstracted, egg-shaped versions of the flags of the contacted countries. On top of each flag he then wrote, in Arabic, transliterations of each response (The Canadian reply? “Please refer to our website”). The paintings are arranged in three long rows on a wall at the Aga Khan.

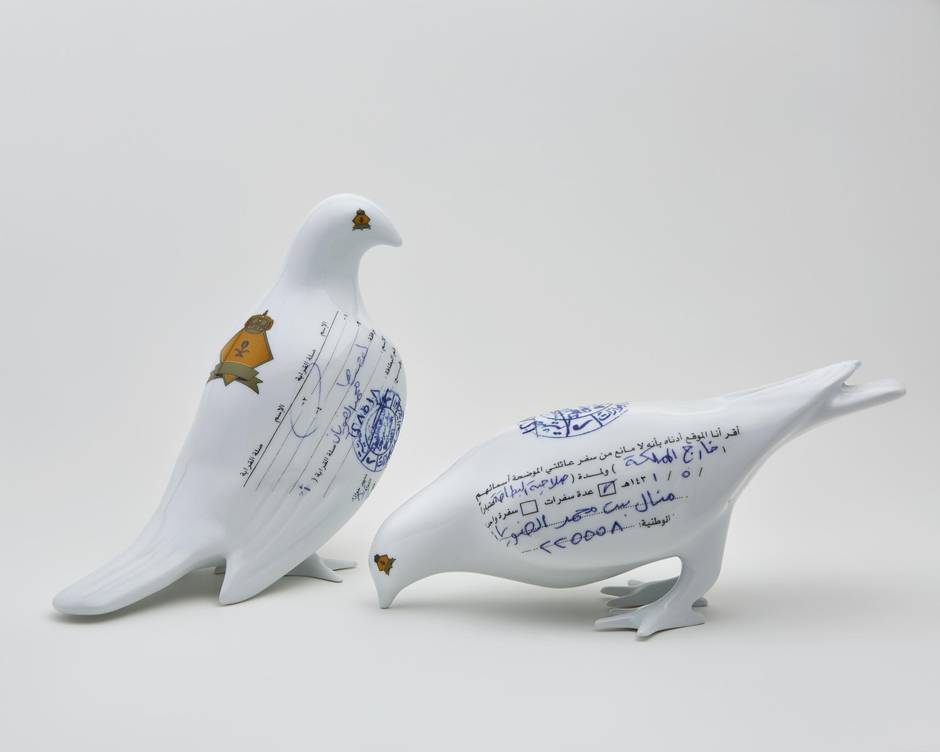

For her commentary on the Saudi practice of forbidding women to travel independently without the written permission of their father or husband or legal male guardian, Manal al-Dowayan fired two lovely porcelain doves on which she imprinted signed travel permits on their folded wings. The work, Suspended Together (Standing Dove, Eating Dove), is part of a larger ensemble piece, some 200 doves, in fact, each one imprinted with travel documents she solicited from high-achieving Saudi women.

Volleyball by 39-year-old Palestinian artist Khaled Jarrar is just that: a volleyball, albeit one made of concrete, using a real rubber-base, leather-panelled ball as the casting mould. What gives the artifact, which is mounted on a plinth, its weight is that the concrete comes from the Israeli West Bank barrier that runs through Jarrar’s home city, Ramallah. The artist clandestinely scraped concrete from the wall to make the ball – inspired, he says, by Palestinian youngsters complaining that the barrier, under construction since 2000, was either eliminating or reducing the size of their playgrounds.

Unsurprisingly, the names of pretty much all of Home Ground’s artists will be unfamiliar to most Canadians. The one likely exception is Mona Hatoum, the Beirut-born, London-based Palestinian installation/video artist who in 1995 was short-listed for the prestigious Turner Prize. An art-world superstar, she’s represented here by two powerful, elegant works. You Are Still Here (2013) is a 38-by-29-cm mirror, affixed at face level to a wall, the surface of which has been sand-blasted with the words of the work’s title, each word forming a line. Infinity, from 2009, strictly positions more than two dozen identical bronzed toy soldiers in the loop symbol for infinity; the loop in turn has been welded to a minimalist bronze side table, thereby rendering its intended use useless. Takesh notes that each soldier is male and holds a gun – and “none is able to see a particular target or direction since, in the loop, his immediate view is blocked by the soldier in front of him.” Infinity – it rhymes with futility and absurdity.

Home Ground abounds with such provocations. (Dig, for instance, Larissa Sansour’s combination video/photography display, Nation Estate, which cheekily adopts and adapts Le Corbusier’s fantastical notion of the Radiant City as the physical “solution” to the issue of Palestinian nationhood.) It’s a valuable show – less, perhaps, than a view into a little-seen art scene but certainly more than a glimpse. Open less than a year, the Aga Khan Museum already feels like an important presence in the country’s cultural firmament.

Home Ground: Contemporary Art from the Barjeel Art Foundation is at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto through Jan. 3, 2016 (agakhanmuseum.org).