Installation view of Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot's Russia, 2024, at The Polygon Gallery.Akeem Nermo/The Polygon Gallery

The exhibition Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot’s Russia starts with a splash. You enter through doors creepily adorned with life-sized cut-outs of two Russian police officers looking over their shoulders at those who might dare to enter this world where rebellion is revered. Then immediately you encounter a video. It is a famous one, of a balaclava’d Pussy Riot member drinking a bottle of water, then hiking up her dress and urinating on a portrait of Vladimir Putin.

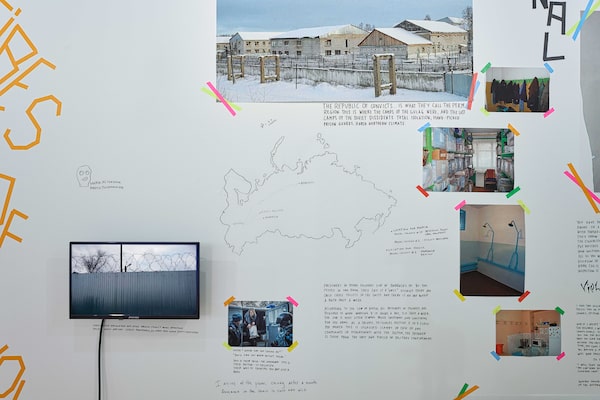

Farther in, the show, on now at North Vancouver’s Polygon Gallery, documents in detail the group’s most renowned act: Punk Prayer, a performance in a Moscow cathedral that launched Pussy Riot onto the world stage – and landed two of its members in a penal colony.

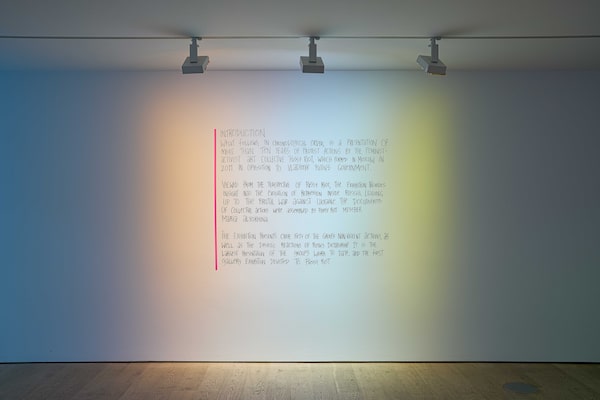

The exhibition, created by Pussy Riot member Maria Alyokhina in collaboration with Icelandic artist-run centre Kling & Bang, traces the punk-as-life feminist group’s “actions,” as they call them, from 2011 when the collective formed in Moscow to nearly present day.

“By following this road to hell, you can see how Russia was changing,” Alyokhina told The Globe and Mail in a recent interview while touring the live multimedia show Riot Days, based on her memoir of the same name, in Western Canada.

In her memoir, Alyokhina – whom everyone calls Masha – writes: “Revolution requires a big screen.” But it’s the small screen that thrust Pussy Riot into the international consciousness. The group creates videos meant to go viral in order to publicize injustices of Putin’s Russia, including escalating autocracy, anti-LGBTQ+ policies, crackdowns on free speech, abuse of prisoners, the annexation of Crimea and the war in Ukraine.

The show tracks the group’s actions chronologically with videos, photographs, handwritten text and graphics. Velvet Terrorism is dynamic, exciting and entertaining. In no way a typical photographic art show, its urgency is the point and its greatest power.

The actions are often biting and provocative – the urine-soaked portrait, the cathedral dance – but never violent. There is humour to them, even beauty – such as when the group flew paper airplanes at the FSB (security services) headquarters in Moscow. But even that kind of gentle protest takes on a sense of urgency, with the omnipresent threat of arrest.

Installation view of Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot's Russia, 2024, at The Polygon Gallery.Akeem Nermo/The Polygon Gallery

Indeed, for this action, Alyokhina spent a few nights in police detention and was sentenced to 100 hours of community service. The house she was made to clean was supposed to be destroyed months later, as she explains in the show: “a very Kafkaesque way to make a punishment.”

Punk Prayer

Every action has a reaction, and the consequences are documented in each section next to a hand-drawn arrow. They begin in 2011 with “nothing serious happened” and escalate to imprisonment, attacks and, ultimately, Alyokhina’s 2022 escape from Russia, amid what she calls a “carousel” of arrests and detentions.

The turning point in Pussy Riot’s history is Punk Prayer. On Feb. 21, 2012, Pussy Riot members entered Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, hopped the barrier guarding the altar, scrambled up the stairs, shed their coats and put on balaclavas. “Virgin Mary, mother of God, banish Putin!” they scream-sang in Russian, part of a song that implored the Virgin Mary: “Be a feminist!”

They were performing in a part of the church where women are not allowed. “The mother of God could not, for example, approach the altar if she were in the cathedral,” the show points out.

They had practised for a month beforehand. “When you go live, you only get one take,” Alyokhina writes in Riot Days.

Afterward, Alyokhina recounts in the memoir, she took the metro to her son’s kindergarten to pick him up, still wearing her green tights and raspberry-coloured dress, the balaclava sticking out of her pocket. “Goodness, you look like you’re going to a party!” the teacher said.

Installation view of Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot's Russia, 2024, at The Polygon Gallery.Akeem Nermo/The Polygon Gallery

The action provoked a grave reaction: Three members of the group were charged with hooliganism, committed for reasons of religious hatred and enmity. Alyokhina and Nadya Tolokonnikova were sentenced to two years in a penal colony.

At one point in the exhibition, visitors enter a small room, meant to replicate one of Alyokhina’s cells. The Russian national anthem, which woke prisoners at 6 a.m., plays on a loudspeaker.

The conditions were horrific. Even while locked up, Alyokhina fought for prisoners’ rights.

After nearly two years, Alyokhina and Tolokonnikova were released in a pre-Sochi Olympics amnesty.

The imprisonment did not shut them up. At the Olympics, they performed the song/action Putin will teach you to love the motherland. There were more actions as Putin’s authoritarian rule escalated beyond Russia’s borders. Alyokhina’s legal troubles also escalated, launching that carousel.

Then, escape. Under surveillance in 2022, she managed to leave her building wearing a bright green food-delivery uniform, including a matching pandemic-era mask, and carrying a square thermal bag. Her partner, Lucy Shtein, had bought the getup online and used it for her own getaway. She got it back to Alyokhina, who escaped in it – in plain, neon green, sight. This landed them both on Russia’s federal wanted list. The uniform and insulated bag are displayed in the show.

Installation view of Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot's Russia, 2024, at The Polygon Gallery.Akeem Nermo/The Polygon Gallery

Masha

Alyokhina, 35, was an activist first, she says, and then became interested in art. The inciting issue in her political awakening was ecology. She learned on social media that Russian officials were planning to cut down her favourite forest. “I didn’t know anything about how to protest.” Still, she began to organize demonstrations.

Then, in 2009, a friend asked her to record a courtroom action to expose the prosecution of two art curators of a show called “Warning! Religion.”

Pussy Riot formed in 2011. When Punk Prayer made international news in 2012, the group was often described as a punk band. Incorrect. “We’ve never been a music band, never,” Alyokhina says. “We are political artists and activists. We’re fighting Putin’s regime.”

Art can be an effective political tool, as this exhibition demonstrates. It documents the high-profile attention and support Pussy Riot has received, from Madonna to the cover of Time magazine.

“I have this power to change a state of mind, views of people, give them other pictures,” Alyokhina says. The Putin regime’s response to Punk Prayer is evidence of this, she says. “They start to be afraid. It means that it has an impact.”

The show has been installed in other cities, including at Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, and has responded to events. With the recent death of Putin critic Alexey Navalny, a caption next to his photo required an extra sentence: “Murdered in ‘Polar Wolf’ Penal Colony on 18 February 2024.”

Installation view of Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot's Russia, 2024, at The Polygon Gallery.Akeem Nermo/The Polygon Gallery

The experience of the show can also shift. I went last Sunday, the Day of Mourning in Russia after the concert hall terrorist attack that killed more than 130 people. It was impossible not to feel connected with Russians in a profound way. The world the show documents and responds to is fluid, and that makes it feel alive in a way that art exhibitions often are not.

“To me, it’s not a retrospective of their work,” says Polygon director Reid Shier. “This is forward pointing. This is about the persistence of resistance against something that has been growing in which they have been calling attention to, and is coming into some sort of horrible fruition as we speak.”

Even since last Sunday, things have changed. This week, Shtein was sentenced in absentia to six years in prison for anti-war media posts. The experience of the exhibition transforms because the context – i.e. the world – remains in constant flux.

“It’s growing all the time,” says Alyokhina, about Velvet Terrorism. “It’s a live thing.”

Installation view of Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot's Russia, 2024, at The Polygon Gallery.Akeem Nermo/The Polygon Gallery