Canadian artist Agnes Martin receives the Golden Lion Award for her overall work from Germano Celant during the inauguration and prize ceremony of the Biennale in Venice on June 15, 1997.Fernando Proitti/Associated Press

Some artists take a position in the public mind that seems almost geological in its solidity. The Canadian-born painter Agnes Martin, for example, was renowned during the last years of her long life as a wise woman of the desert, who issued oracular statements from her adobe compound in New Mexico and painted abstract canvases that many people experience as windows into tranquility.

A new biography of Martin, who died in 2004 at the age of 92, offers a very different picture, of a turbulent life wracked by schizophrenia and deep fear of chaos. In Agnes Martin: Pioneer, Painter, Icon, Irish writer Henry Martin (no relation) says that for much of the artist’s life, the serenity of her paintings was a condition to which she aspired, not one she lived.

This undated photograph shows American abstract painter Agnes Martin in her studio.AP Photo/Courtesy of the Harwood Museum of Art, Mildred Tolbert Archives

The book also contains fascinating revelations about Martin’s early life in Canada. Although she became famous while living in New Mexico, her strong connection with land and water seems to have been formed during her years in Western Canada.

Martin is the most internationally celebrated artist ever born in Canada, though much less familiar in the land of her birth than Tom Thomson or her fellow abstractionist Jean-Paul Riopelle. The Guggenheim Museum showed a retrospective of her work in 2016, the same year her painting Orange Grove sold at auction for a record $13.7 million – a couple of million more than the record for Lawren Harris and nearly double the top price for anything by Riopelle.

Martin was born in Macklin, Sask., in 1912, a child of Scottish immigrants. Her father was a veteran of the Boer War; his cousin was John McCrae, who wrote In Flanders Fields. After her father’s death, her forceful mother moved the family to Vancouver in 1919.

Martin was a sporty, adventurous young woman who “would make boats out of apple barrels that she would then try to sail up the Fraser River,” her biographer writes. She was a strong swimmer and a runner-up in tryouts for the Canadian Olympic swim team in 1928. Water remained important to Martin throughout her life, as a spiritual ground for the delicate hand-drawn horizontals in her paintings.

A gallery of works by Agnes Martin, part of a ten-story addition to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, is pictured on May 12, 2016.JASON HENRY/New York Times

She also worked in lumber camps and spent time in the Rockies, where she led parties of tourists on hiking trips. One client was William O. Douglas, a long-serving judge on the U.S. Supreme Court. “The big thing, when you’ve got William Douglas on,” Martin later recalled, “[is that] you have to take three extra burros for the alcohol.”

She moved to Bellingham, Wash., in 1931, initially to help her sister with a new baby. There she had her first major sexual relationship with a woman and began a long pattern of entering intense female friendships, usually with younger women she would later edit out of her life. For Martin, love was a form of chaos and friendship an invitation to dependency.

She attended teachers college in New York, where she visited museums for the first time, and taught school in Oregon through the Second World War. It was only in 1946, when she was 34, that she made her first significant move to become an artist, by entering the summer art school in Taos, N.M. She made big, vivid watercolours in the mountains, many of which she later destroyed. She was a fierce editor of her work throughout her career, often buying back pieces to slash them up with a box cutter.

The new biography includes many reminiscences of Martin by people who knew her, gleaned from interviews the author did while doing research for the 2016 film, Agnes Martin Before the Grid. Friends say that she had “a spiritual side that was just glowing,” but also remember a paranoid, obsessive character who “could be mean as anything.” She might withdraw for long periods, or talk without pause for many hours at a time.

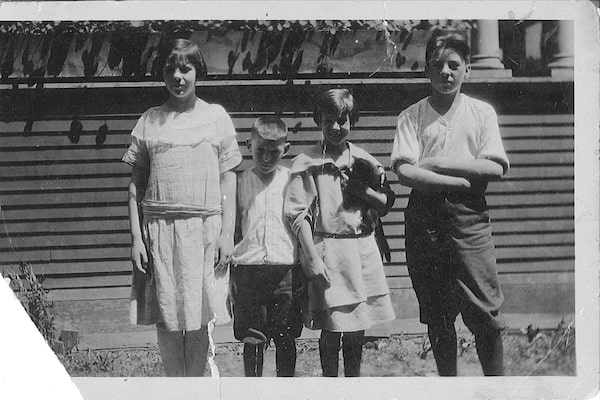

The Martin children (left to right): Maribel, Malcom Jr., Agnes with cat, Ronald).Courtesy of Christa Martin, Martin Family Archive

Martin also heard voices in her head and had long conversations with them, sometimes taking their advice on career decisions. While developing her art in New York in the 1960s, she sometimes became violent or incapacitated, more than once being taken off the street by police, unable to give her own name. She was forcibly confined at Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital, where she was subjected to repeated electroshock treatments that eroded her memory in later life.

And yet, during this same period, the elements of the grid paintings for which she is best known were coming into clearer view. The classical orderliness of these large, square, uniform canvases is offset by their small hand-made deviations from strict organization. Martin’s work was beginning to sell, she was represented by an important gallerist (Betty Parsons, which whom she also had an intimate relationship), and she was discussed as a key figure in what was being called Minimal Art – a term she never accepted.

In 1967, however, she suddenly dropped out, gave away her brushes and paints, and left New York for a restless, 18-month ramble around North America. Apparently, she thought her days as a painter were over. She spent the winter in Canada, driving 9,500 kilometres across the country and working at the same kinds of odd jobs she had done as a teenager. “I am staying unsettled and trying not to talk for three years,” she wrote in a letter to one of her New York patrons.

Martin’s informants don’t have much to tell us about her Canadian odyssey, perhaps because she was in flight from everything and everyone. It’s tempting to think that she was drawn back to the land. She stayed in “empty, snow-buried forest camps,” her biographer writes. Could any solitude be greater or more Canadian?

Martin tended to paint in series and to revisit ideas, sometimes years or decades after they had first arisen.Gary Lee/Newscom

Eventually she returned to New Mexico, rented land an hour’s drive from her sometime friend, artist Georgia O’Keeffe, and lived a hermit’s life, building a house, studios and sheds from adobe bricks she made herself. Her period of solitude and exile from art lasted until 1973.

In that year, Martin produced new paintings, a book of sparse and luminous writings and a very successful collection of prints called On a Clear Day. She was profiled in the Village Voice and given a retrospective at Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art. The art world rediscovered Martin, who was ready to be found and to participate in the myth of the desert seer that quickly formed around her.

As her biographer points out, her writings won fans among people who had never seen her paintings. In that sense, Martin was like the composer John Cage, whose books reached a much bigger audience than his music. In both cases, the writings tended to become a prism or filter through which the art was experienced.

Martin herself had an ambivalent relationship to words about art. She enjoyed lecturing about it, but sometimes became fiercely adamant that the only connection that mattered was the direct one between viewer and painting. A 1980 offer of a solo exhibition at New York’s Whitney Museum came to nothing because Martin refused to let the museum produce a catalogue for the show.

Agnes Martin is pictured in 1993.courtesy Dan Budnik Archive

Painting was always hard for Martin, invariably dragging her through feelings of failure and desolation until she received the inspiration she had waited hours, days or weeks to find. She tended to paint in series and to revisit ideas, sometimes years or decades after they had first arisen. Unlike some artistic careers, in which peaks and valleys of accomplishment imprint themselves on the public mind, Martin’s output has a kind of generalized, cumulative force, like a big stretch of Saskatchewan prairie.

“When people think of her work,” Martin writes, “they are left with a visual impression or feeling, rather than one specific image.” That would probably have suited the painter, for whom the canvas was a site where feelings about one’s place in the world, including the natural world, could be revealed and intensified.

After decades of poverty, Martin spent her last years as a wealthy woman. She became a significant philanthropist in her New Mexico community. One of the projects she financed was a swimming pool. She painted almost to the end of her life, often filling her canvases with bands of colours she saw in her environment.

One day in 2004, a few weeks before her death, an ailing Martin asked a painter friend to sing her a song. The friend chose Ian Tyson’s Four Strong Winds, a song about being unsettled and ending relationships. It’s also a very Western Canadian song, in its reference to Alberta, but also in the way it projects a feeling of open country. Perhaps it reminded Martin, for whom the horizontal was always the primary way into a canvas, of the first horizons she had known, thousands of kilometres to the north.