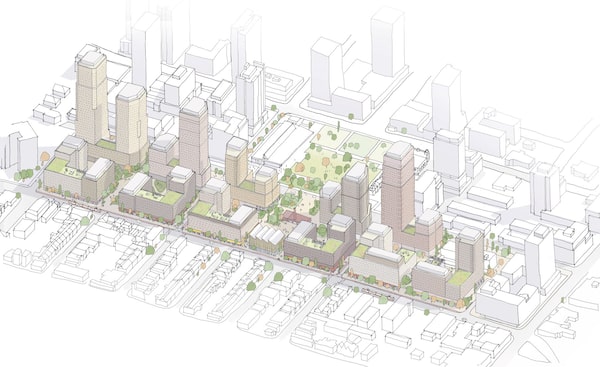

Toronto Community Housing Corp. and private developer Tridel have applied for planning permission to rebuild the final sections of Regent Park in Toronto.Karakusevic Carson Architects/TCHC/Tridel

The revitalization of Regent Park has taken another step. Last month, Toronto Community Housing Corp. and private developer Tridel applied for planning permission to rebuild the final sections of this downtown neighbourhood.

The new plan, if approved, would replace a previous scheme from 2014. The new one sets a good example for public building projects: It is economically integrated, thoughtfully designed and dense. Toronto should see it through, and learn from it.

The area in question fills 16 acres along Gerrard Street between River and Parliament streets. The 2014 plan called for 1,900 subsidized and market-rate homes. The new one adds nearly 1,800 market-rate homes and more than 500 new subsidized homes.

The result, shaped by London’s Karakusevic Carson Architects, looks like something out of a London borough: a district of mostly mid-rise buildings organized around courtyards. A handful of highrises sneak in a few hundred extra homes. A new Toronto Public Library branch is now planned to stand in the middle. A community centre in a repurposed power station provide places to gather. New shops on the ground floor offer jobs and street life.

Drawing of the proposal for the Regent Park neighbourhood.Karakusevic Carson Architects/TCHC/Tridel

In short, this seems like sensible and thoughtful city-building. It differs completely from the radical approach that governments took in the 1940s to create this place originally, destroying 69 acres of existing buildings and streets to scatter new apartments across a no man’s land of lawns. Straightforwardness is a good quality in urban design.

But straightforwardness isn’t enough. It’s also important to use space efficiently. In the first phases of Regent Park’s rebuild, “we heard from residents that there were things that were missing,” says Peter Zimmerman, senior director of development at Toronto Community Housing Corp., or TCHC. “We had a lot of interest in community gardens and green space.”

However, the 2014 design for this section of Regent Park would have filled almost all of the site with buildings – mostly townhouses with a few mid-rise buildings. “By concentrating the density and moving it from low-rise to mid-rise, and mid-rise to high-rise,” Mr. Zimmerman explained, “we were able to increase our density, get more affordable housing, get a new library and get more outdoor space as part of the plan.”

The logic is simple: Taller buildings; housing more people. Fewer private backyards; more public space.

The revitalization will, as it has in the past, proceed without displacing any existing residents. The plan replaces all of the area’s existing 2,083 subsidized homes while adding new condominiums. The latter both fund the project and integrate the neighbourhood economically.

The new plan includes 633 homes that replace existing rent-geared-to-income units, and creates space for about 500 more non-market homes. The degree of affordability for those 500 “depends on how the city, the province and the federal government respond to the plan that we’ve done,” Mr. Zimmerman said.

How is the plan being received? Raisa Chowdhury, who grew up in the neighbourhood and has served on a TCHC advisory board, said that current residents are generally receptive. “Residents don’t want a distinction between community and condo buildings,” said the planning student at Toronto Metropolitan University, formerly known as Ryerson University. “And I’ve been hearing a lot about the need for locally owned businesses.”

Both TCHC and Tridel confirm that those ideas are baked in. “Our intention is that the market and affordable buildings will be indistinguishable, and of high-design quality,” Tridel vice-president Michael Mestyan said.

The details will matter, and they will depend on the designers. Both TCHC and Tridel make encouraging noises about hiring Karakusevic Carson, who are experts in social-housing rebuilds, to design these buildings in detail, but this is not yet set. The one piece of adaptive reuse, turning a power plant into the community centre, is still under discussion. (It absolutely should stay.)

Still, the basics here are sound, and refreshing. For half a century, Toronto planners and other civic officials have been leery of apartment buildings. Many hours have been wasted listening to neighbours complain that a given building is too tall. But Toronto is a city, and a city should house a lot of people – in economically integrated neighbourhoods with high-quality public amenities.

If that’s the next chapter in Regent Park’s evolution, it’s a lesson for Toronto’s future.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.