The director of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) was shocked to discover that the National Gallery of Canada is selling a work by Marc Chagall in an apparent bid to compete for an Old Master painting that she hopes to buy in tandem with another Quebec museum.

“I was as surprised as you are,” said Nathalie Bondil, whose museum teamed up months ago with the Musée de la civilisation in Quebec City in an effort to purchase a painting by Jacques-Louis David, of St. Jerome hearing the trumpets of the apocalypse. “We know that there is an offer from the National Gallery, but I was never contacted by Ottawa, neither me nor Quebec.”

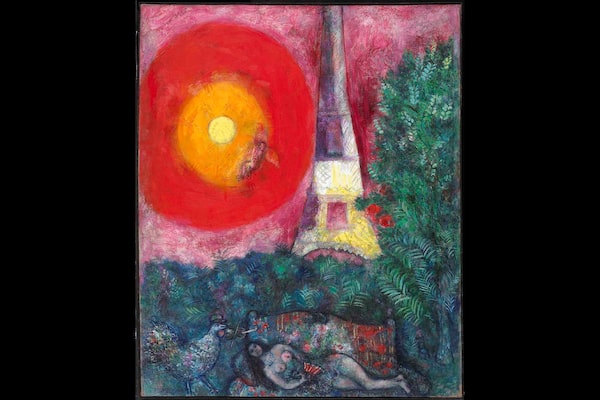

National Gallery director Marc Mayer drew headlines and a wave of criticism earlier this week when he announced that the National Gallery would sell Chagall’s 1929 canvas La Tour Eiffel at auction next month, and use the proceeds to buy a painting of national importance that would otherwise leave the country. That doesn’t apply to the David canvas, Ms. Bondil said.

“The David would have stayed in Canada,” she said. “It’s classified. It would not be sold abroad, it’s protected heritage.”

National Gallery director Marc Mayer drew headlines and a wave of criticism earlier this week when he announced that the gallery would sell Marc Chagall’s 1929 canvas La Tour Eiffel at auction next month.National Gallery of Canada

Ms. Bondil said her efforts to reach Mr. Mayer had had no result by the time she spoke with The Globe and Mail on Thursday afternoon. Repeated requests from The Globe also received no reply.

Stéphan La Roche, Ms. Bondil’s counterpart in Quebec City, confirmed that he had heard nothing about the National Gallery’s interest in the David painting from the gallery itself, even though his institution holds the work on behalf of its owners.

The David, which like the Chagall is worth millions, has been on display at the MMFA since 2016, on loan from the Musée de la civilisation. The Quebec museum, in turn, has custody through a long-term loan from the civil corporation (fabrique) of the parish of Notre-Dame de Québec, owner of the painting since 1938. The fabrique reportedly wishes to sell in order to pay for upkeep of two historic churches in Quebec City.

“Our museum has a right of first refusal, as the legal depository of the painting,” Mr. La Roche said. “We have not yet made an offer. There is only one offer on the table, from the National Gallery of Canada, conditional on their selling another work. We have until the middle of June to see what we can do [to match it].” He and Ms. Bondil are looking for private and government partners to provide funds for the purchase, he said.

If the National Gallery were trying to sell a second piece to cover its David bid, it would have to be another multimillion-dollar work, unless the gallery has most of the cash in hand and needs only a top-up from a sale of something too minor to mention. Only one major deaccession – of the Chagall – has been announced.

Ms. Bondil was sharply critical of the decision to sell the Chagall at auction in New York next month, which she described as “an emergency.”

“Selling a painting is a very drastic, extreme solution,” she said. “They receive $8-million per year in public funds for acquisitions. That’s a lot of money. Why is that money not being used for this purpose? Why are they selling a masterpiece from a public collection?”

The timing of the Chagall sale could hardly be worse, in terms of awareness of the artist’s work in Quebec and Canada. Last year, the MMFA staged the biggest Chagall exhibition in Canadian history, attracting more than 300,000 visitors.

Ms. Bondil said she would welcome a “win-win-win” situation in which the Chagall stays in Canada, and the David is shared among museums.

“It’s so, so difficult to acquire great paintings,” Ms. Bondil said. “That is why we wanted to work together, and not compete against each other. We could even have a three-way ownership. Why not? That would be an interesting approach.”

Joint ownership between two or more institutions is rare, but could become more common as prices escalate. In 2015, the Louvre in Paris and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam agreed on a joint purchase of two portraits by Rembrandt.

Mr. La Roche said a joint purchase would be a first for his institution, but worth pursuing in light of the importance of the David painting for Quebec and his museum. It’s the only work by the French neoclassical artist in the province, he said, and the only part of an important collection amassed by sisters Henriette and Geneviève Cramail that is not already lodged in the Musée de la civilisation. From 1922, the painting was displayed at the historic Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Quebec City.

The National Gallery’s acquisitions policy provides for joint acquisition, when that might “help other institutions” and meet “compatible and complementary objectives.” That would seem to apply in the case of the David canvas, now at the heart of a tug of war between major public museums.