This exhibition Renaissance Venice: Life and Luxury at the Crossroads at Toronto’s Gardiner Museum features maiolica storage jars and Paolo Veronese’s Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine.Toni Hafkenscheid/Handout

The 21st century is the era of globalism; Canada is the pioneer of multiculturalism and Toronto is its epicentre. Or maybe not. At the Gardiner Museum in Toronto, the powerful message behind an exhibition of decorative arts from Renaissance Venice is that lively cultural and economic exchanges were swirling around the globe long before the advent of mass communication and rapid transportation.

Take, for example, an earthenware bucket with floral motifs on a light blue ground dating to 1570: The property of a well-born nun and marked with her family crest, it was used to hold holy water. Yet, its shape is borrowed from the brass buckets of Islamic metalwork, its blue-tinted glaze is inspired by Chinese ceramics and its twirling patterns of flowers and vines resemble those of Iznik ware from Turkey.

The tin used in its glaze would have been imported from mines in Cornwall but the bucket itself would have been made in a Venetian workshop. Local artisans were introduced to Asian crafts through imports brought across the Mediterranean by the merchants of the Mamluk Sultanate, centred in Egypt, and later the Ottomans. In Venice, the watery city of art and trade, cross-cultural currents flowed strongly.

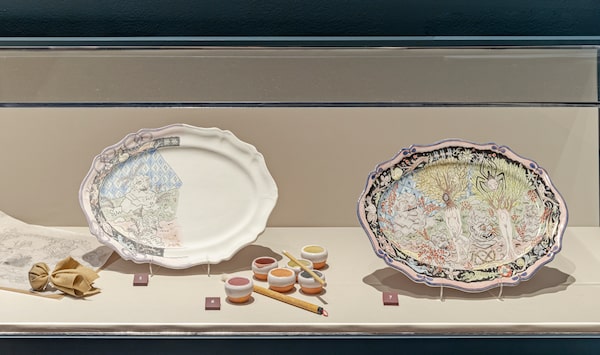

Daphnes and Lauras by contemporary artist Lindsay Montgomery shows the technical process for creating the tin-glazed earthenware known as maiolica.Toni Hafkenscheid/Handout

This exhibition, titled Renaissance Venice: Life and Luxury at the Crossroads, is built around the Gardiner’s own collection of maiolica, the tin-glazed earthenware made by the Italians using techniques imported from Islamic Spain. Applied to the unfired clay, the tin glaze creates an opaque white ground that can be painted on with pigments like a plaster fresco: The artist can’t correct any mistake, but when fired, the ceramics retain the bright colours.

To demonstrate the technique, the show includes a contemporary piece by the Canadian artist Lindsay Montgomery in various stages of production. Meanwhile, the 16th-century results of a ceramic medium that permitted strong colours and detailed representation are on spectacular display. There are big blue-and-ochre jars with patterns of green leaves that were used to store food or pharmaceuticals, and there are large blue-and-white chargers with claustrophobic patterns of vines, fruit and flowers, the best examples on loan from London’s Victoria and Albert Museum.

A 16th-century filigree glass cup, on loan from the Corning Museum, is an example of Venice’s most famous decorative exports.Toni Hafkenscheid/Handout

As they decorated these surfaces, the artists rejoiced in the narrative capacity of the medium. There are multiple storytelling plates here depicting figures from the Bible and from myths, such as Venus, shown plucking a thorn from her foot, or Neptune, the sea god who appealed to Venetian geography. Earthenware was not high luxury (compared with porcelain or metal) but its intense decoration was prized both for use at the table and display on the shelf.

That’s the backbone of this show; its many limbs, thanks to strategic loans from such neighbours as the Royal Ontario Museum and the Textile Museum of Canada, feature the other decorative arts that were imported to or produced in Venice. A 15th-century Ming Dynasty bowl, a gorgeous example of China’s distinctive porcelain, loaned by a private collector, reminds viewers of the original source of those pleasing blue-and-white palettes mimicked in the maiolica. Alongside a display of historic pieces of lace, there’s a woodcut print by Albrecht Durer that features the knot patterns Europeans had assimilated from Islamic culture with its use of interlocking arabesques. The print, in turn, is a precursor of the pattern books that would help lacemakers reproduce these intricate designs with literal knots.

Curator Karine Tsoumis investigates not only the artistic influences and narrative themes of these arts but also the social realities of production, including side notes about the status of women. A few of the potters, many of whom migrated to Venice from other areas of Italy, were renowned enough their names have come down to us from family workshops where female artisans worked alongside their male relatives. Lacemakers were perhaps the most exploited, poorly paid workers who fashioned trappings for the richest of the rich.

And, of course, there is Venetian glass here, the most famous of the city’s decorative exports. The pieces, on loan from the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, N.Y., are remarkable not only for their fine, fragile shapes but also for their mere survival, 500 years after they were blown.

One such piece sits in front of a banner featuring a reproduction of Paolo Veronese’s Wedding Feast at Cana: The original hangs in the Louvre and the painting depicts a sommelier swirling wine in a very similar wide-bowled filigreed cup. (And, as noted in the text accompanying it, the painting also depicts a Black boy waiting on table, a child victim of the slave trade.)

But mainly that banner underlines what this show is not: an exhibition of Venetian painting, although you might not know that from the marketing posters around town. Reproductions of several paintings such as the Wedding Feast are used to illustrate the decorative pieces used in Venetian homes and palaces, but there is only one actual canvas on display – Paolo Veronese’s The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine on loan from the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Featuring the saint, dressed in a shimmery gown of grey-and-white damask, meeting the Virgin and Christ Child under billowing red velvet drapery, it is used to illustrate the visual richness of the Venetian style with its heavy use of saturated colours and numerous decorative motifs. This show touches only lightly on the winners and losers of global trade, but in a sea of international influences, Venice’s wealth did produce delicacy and delight.

Renaissance Venice: Life and Luxury at the Crossroads continues at the Gardiner Museum to Jan. 9.

Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor