Artists and mentors of the Qaggiavuut! School of Performing Arts.Qaggiavuut

In the time of Rhoda Ungalaq’s parents, and that of her grandparents, and for as long as anyone can remember, live performances in Nunavut took place in massive igloos called Qaggiq.

Ungalaq’s father was among the men who built those structures. And, when they stood tall and inviting, he would call out “Qaggiavuut!” to everyone in his community. It means “come and celebrate.”

Under the rounded walls of snow and ice, people would tell stories and dance to beating drums. The women would try to best each other at throat singing. And the children would be steeped in both the language of their ancestors and the stories of legendary creatures and magic men that had been passed through the generations.

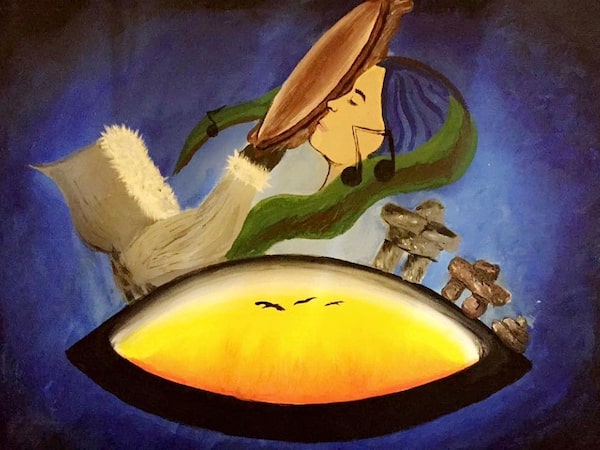

This artwork, called The Boy Drums, The Woman Sings, is by Tooma Laisa.

Those performances stopped with the arrival of European missionaries. The songs sounded satanic to the ears of the 19th and 20th-century Christians. And, as the people were moved off the land and into small communities, the snow-house theatres became a thing of the past, as did the dancing and the singing and the drumming.

The missionaries “didn’t understand.” The community had survived because of their songs, Ungalaq says. "When you are singing your songs, it is healing.”

In the past decade, there has been a revival of Inuit live art. Young Inuk men and women are recreating the old songs for the people of Nunavut, and for audience members around the world who are getting their first taste of a culture that was muffled by the censure of colonizers – a culture that has been reborn after edging perilously close to extinction.

Tiffany Ayalik is an Inuk singer, actor and dancer.

The problem is, there is no dedicated space for the revival to take place. Nunavut is the only jurisdiction among Canada’s provinces and territories that does not have a theatre for live performances.

But as this revival has taken root, an almost 10-year-old non-profit arts society has been working to solve that problem, and now the group is asking Ottawa for $30-million – half the funding they need to make that dream a reality, or less if they must reduce the scale of the project to fit a tighter budget.

The society, which is made up of Ungalaq, Ellen Hamilton, Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory, performing artists and other supporters is named Qaggiavuut! – after the old call to come and celebrate. Hamilton is now the executive director of that society, Bathory is the artistic director and Ungalaq is the chair of the board.

They have been working to build a place for live cultural events in Iqaluit – one with a large stage, but also with rehearsal places and classrooms for teaching the performing arts, and rooms where Inuit children can be immersed in their language and heritage. And they have enlisted notable Toronto architect Donald Schmitt to create a design. The theatre they hope will be the end result will be called Qaggiq: Nunavut Performing Arts and Cultural Learning Hub.

This artist's rendering shows a view of the proposed theatre complex.

The funding from the federal government is a tough ask at a time of deficit budgets, and when money is needed for social programs, health care, the environment and myriad other competing interests. But supporters say it is an important project that deserves financial backing.

Adrienne Clarkson, the former governor-general, says there is something special in the vision that Inuit people bring to the world, especially in terms of space and light. And the expansion of their culture, she says, depends very much on having a central place for their performing arts.

“Inuit culture is like any other. It must be constantly fed, encouraged and developed,” Clarkson says. “Only with an artistic performing space and home can this kind of expression be encouraged and sustained.”

Next year is the young territory’s 20th anniversary. It is also the International Year of Indigenous Languages. And the members of Qaggiavuut! are hoping the confluence of dates will spur federal decision-makers to look northward and to consider the warmth that a theatre could bring to the coldest part of Canada.

“We see Qaggiavuut! as being a catalyst for a school of performing arts,” Hamilton says, “a place for youth to come and learn the arts from their own Inuit people, for the tourists to come and see Inuit art at its highest professional level and for us to create work that can be exported back into our own communities and also around the world.”

This artist's rendering shows the interior of the proposed Qaggiq: Nunavut Performing Arts and Cultural Learning Hub

Hamilton, Ungalaq and Kathleen Merritt, a throat singer who is Qaggiavuut!’s program manager, were in Ottawa in early December to petition the government for the money they need to start construction. If they could get a commitment in the next federal budget, they could break ground next summer, Hamilton says.

Pablo Rodriguez, the Minister of Canadian Heritage, did not return requests for comment.

High-calibre live performances are being created in Iqaluit, even now. But rehearsals have been held in church basements and in the community soup kitchen. After lunch is over, the performers move the tables and bring in lighting and speakers and map out a stage on the floor with tape.

Inuit youth, meanwhile, are sent to attend courses in southern Canada to learn about their culture and their performance art.

And, while some Inuit plays are staged in a local hotel, Merritt says "it takes away from the artistry because, every single day, you have to go in and build a stage and you have to build the sound, you have to build all the lighting, which takes hours. Then you have to tear it down because there is another event coming in.”

Space to create the productions in the first place simply does not exist, even for shows that have gone on to garner international acclaim.

A few years ago, the members of the Qaggiavuut! society began gathering the tales of their ancestors. The songs that relayed the stories through the generations were banned, but they were preserved, Ungalaq says, “because the elders used to sing them under their breath, quietly.”

Ten young Inuit actors were selected, along with four elders, to weave the stories into a piece of theatre.

First, they collaborated and rehearsed by crawling around the offices of the Qaggiavuut society. Then the Isabel Bader Centre for the Performing Arts in Kingston, Ont., offered some space so the youth were sent south but the elders, who were too frail to travel, could not join them.

That is how Kiviuq Returns, the epic retelling of an Inuit hero’s travels through a mystical world, was created. It is the first full-length Inuit-language theatre production in Canada and has had runs in Kingston, at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa and at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity.

In January, it will play at Toronto’s Tarragon Theatre. And promoters in China are negotiating a 50-performance tour, as are promoters in Europe and the United States.

But in Nunavut, it has only been performed twice – both times in an Iqaluit school gym.

Kevin Loring, the artistic director of Indigenous theatre at the National Arts Centre, says it is expensive to build anything in the North, but cultural preservation is important.

“We often talk about our sovereignty in the Arctic," Loring says. “Maybe that means icebreakers patrolling the oceans, but I also think it means that we should have these kinds of cultural spaces where we are telling our stories and we are fostering the culture that comes from there.”

Storytelling leads to social well-being, Loring says. Seeing oneself reflected on stage, and understanding that local stories have value, he says, reverberates into the community.

Natashia Allakariallak is one of the stars of Kiviuq Returns.

Schmitt, the architect, says he also wants Nunavut to see itself in his design.

There were three major considerations that went into his concept for a performing-arts centre. The first, Schmitt says, was that it would be a place for people of all ages and diverse interests to gather. The second was that it would create a sense of shelter from the environment, so it has an aerodynamic side that deflects wind and snow.

And the third objective, he says, was to reflect the form of the ancient snow houses of the sort that were built by Ungalaq’s father.

When a previous story about Qaggiavuut!’s interest in building a theatre in Iqaluit ran in a southern newspaper, commenters suggested the Inuit should go back to their massive igloos. Asking the Inuit to stage their production in snow houses would be like asking a European symphony orchestra to perform in a tent or a cave, says Ellen Hamilton, a Nunavut resident and performing artist.

Basic necessities such as food and shelter are always in short supply in Iqaluit. So the women of Qaggiavuut! say they recognize some people will also argue it is folly to put millions of dollars into a theatre when the money could be used for more practical things.

But Ungalaq says, for the Inuit, performance art is linked to survival.

In the time of the ancestors, when it was winter and 50 degrees below zero, the goal every day would be to find food, she says. When someone came back to the community with a seal, there was feasting and there was a celebration and much signing.

“There is a song that says "we will survive again, the two stars have appeared and the daylight is going to be long again, and we will be sleeping in the light again,” Ungalaq says. Performance in that way, she says, was and remains an essential part of Inuit life.

Today, she says, the biggest fight is not to find food, but to stop the feelings of helplessness and depression that cause Inuit youths to take their own lives at rates that are 30 times higher than the rest of Canada.

And that is the main reason why a performing arts hub is so important, Ungalaq says. “The language is disappearing, the culture is disappearing. If we can erect our language and culture, more will survive."