This evidence photo released by the Ontario Provincial Police in Canada shows forgeries of artwork by legendary Canadian Indigenous artist Norval Morrisseau.Ontario Provincial Police/AFP photo/Ontario Provincial Police

The elderly couple embraced in the courtroom until security staff had to separate them.

“Why did they keep us apart so long?” sobbed 82-year-old John Goldi, as he stooped to hug his wife, Joan, in a wheelchair.

“I love you,” said Joan, aged 80.

They had spent the previous seven nights in Ontario provincial jail awaiting a contempt of court hearing, one of the strange legal side-shows originating from what police are calling the biggest case of art fraud in Canadian history.

In March, investigators with the Thunder Bay Police and Ontario Provincial Police arrested eight people for allegedly counterfeiting between 4,500 and 6,000 pieces of art credited to Norval Morrisseau, an Indigenous artist who died in 2007. With an average Morrisseau going for $15,000, the value of alleged forgeries could approach $100-million, police said.

The Goldis were not among those implicated in the fraud, but their ample legal problems are directly linked to the authenticity war over Morrisseau’s work. Online and in court, the Goldis have for years declared themselves defenders of Morrisseau’s legacy, attacking anyone who dared to speak out about fake paintings. In their view, the forgery claims, which date back to the mid-nineties, were part of a grander conspiracy, cooked up by a cabal of art elitists who wanted to drive up Morrisseau prices by declaring vast swaths of the artist’s oeuvre fake. As former award-winning documentarians who worked with the likes of author and broadcaster Linden MacIntyre, they held themselves out as fearless truth-tellers – most notably on their blog, TheNorvalMorrisseauHoaxExposedBlog.com.

“This blog searches out and scorches those people in prominent positions whose racist participation in promoting an art fraud have undermined the public trust in the integrity of the art and artists of Canada’s Indigenous people,” John wrote on the site’s “Credo” page.

This April, five years after those words appeared online, the Goldis sat in court and received their own scorching from Justice David Corbett, who called their efforts to evade the court “a disgrace” and went on to remind them of all they’d lost during their self-destructive battle: the blog had been shut down; they owed roughly half a million dollars for defamation; their house was about to be auctioned off by the sheriff’s office.

John – who describes himself as a Canada’s top investigative journalist and honorary curator emeritus of an online Boer-War museum he created – could only reason that he was being targeted by the courts.

“They’re weaponizing the judiciary, just like Trump has said,” he told The Globe and Mail after the hearing. “There’s no justice here. You can’t fight them. Donald Trump has millions of dollars to fight these guys. I don’t.”

A reporter walks past Androgyny by Norval Morrisseau, right, and Tweaker by Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun during a media tour of Canadian and Indigenous Art: 1968 to Present, at the National Gallery of Canada's contemporary art galleries, in May, 2017.Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

The fight dates back to about 1995. Parkinson’s disease had robbed Morrisseau’s ability to paint, but gallerists and art scholars noticed a flood of Morrisseau canvases arriving on the market. They told collectors to be wary of Morrisseau paintings, especially those signed on the back in faded black paint, a method called black dry-brush that some art scholars say Morrisseau rarely, if ever, used.

Morrisseau himself took notice, and identified more than 100 works as fake before his death at the age of 75. One of his proteges, a painter named Ritchie Sinclair, took up the cause as well, launching a website showing images of 1,000 paintings he thought to be fake. It was no easy task. Arguably the country’s best-known Indigenous artist, Morrisseau produced thousands of works and off-loaded them in haphazard fashion. Some he sold through high-brow dealer networks for five-figures sums, others he bartered to friends and family for a meal or a drink. There is no definitive catalogue.

The backlash from owners of the contested paintings was immediate. The Goldis, who acknowledged in court filings that they owned at least two black dry-brush Morrisseaus, started their blog in 2013. John took credit for the writing and research, while Joan was webmaster for the couples’ websites (they also operated sites devoted to the Boer War and their art and antique collection). The blog took aim at the whistle-blowers with an unhinged and self-destructive intensity.

John compared a group of volunteer academics working to authenticate Morrisseau’s work to Nazi book burners and called them “The Apostles of the worst act of cultural genocide in Canadian history.”

He accused Sinclair and his associates of “murdering” a Globe and Mail journalist who wrote about the suspected fraud in 2007. In reality, she died of brain cancer the following year.

He likened Jonathan Sommer, a lawyer representing a number of art collectors who believed they bought fake Morrisseaus, to a murderer, a mafia member, a con-man and a leader of an international conspiracy intent on cornering the Morrisseau market, according to court documents.

In the wake of those posts, Sommer lost clients. He couldn’t sleep. His health declined.

“They went to the heart of my ability to practise law,” he said. “Ultimately their message was that I was a dangerous, violent, corrupt liar and scammer. And also deeply immoral and a racist.”

The blog had a distinctly Web 1.0 feel – full of rudimentary photoshopping and alternating font colours – and it didn’t draw huge audiences. But art experts say the blog played a key role in preventing people from coming forward to talk about the alleged fraud.

“The problem has been that there’s been so many people defending this in a very aggressive way that most of us basically have been afraid to step out and identify a fake,” said Bill Mayberry, president of Mayberry Fine Art, whose sole effort to help educate the public about authenticity issues with Morrisseaus resulted in years of hate mail, he said, while the Goldi blog accused him of an “unforgivable act of cultural genocide.”

The Goldis used the justice system as well, filing against Sinclair in small claims court for featuring one of their paintings on his website of suspected forgeries. The claim was eventually withdrawn. They also sued CTV and The National Post for running stories on the alleged counterfeiting, claiming negligence and injurious falsehood. Both claims were dismissed.

In 2012, Kevin Hearn, multi-instrumentalist for the Barenaked Ladies, filed a suit against the gallery that sold him Spirit Energy of Mother Earth. After several experts deemed it a fake Morrisseau, and the seller, Joe McLeod, provided him with two false provenance statements, Hearn hired Sommer and sued.

During the trial, one of his expert witnesses, Morrisseau scholar Carmen Robertson, quit the case because she felt intimidated. She’d become a target of the Goldi blog. In addition, John and another collector, Joe Otavnik, had sent letters to her employer, the University of Regina, questioning her work on the case.

Someone writing under the name Roxanne Spritzer also sent two e-mails to Carleton University, where Robertson was negotiating a new job, with links to damaging statements about her on the Goldi blog. John later admitted that he used the Spritzer account, which was registered in his wife’s name, to hide his identity online. It remains unclear how he figured out Robertson was talking to Carleton.

Justice E.M. Morgan said Otavnik’s conduct was “misguided but not illegal” but called John’s actions “an interference with the judicial process that must not go on.”

Robertson eventually returned to the case, but only after receiving assurances from Hearn. “I had to basically get on my knees and beg her to come back and hire personal security for her from the hotel to the courtroom,” said Hearn, who had his own appearances on the blog.

In one entry, the blog shows a picture of Havana Winter Hearn, Hearn’s daughter living with a disability, and asks, “Why would a caring parent chose [sic] to waste some $250,000 on a specious lawsuit backing a fraud, instead of devoting it to provide the best possible care for his own special needs child?”

Soft-spoken and mild-mannered, Hearn betrays a tinge of anger when the Goldi name comes up. “They said I was a bad father for pursuing this lawsuit, and actually posted a picture of my disabled daughter on their site,” he said in an interview at Noble Street Studios, where the band is recording a new album. “How disgusting is that?”

In 2018, Hearn lost in Superior court. Between the loss and the harassment, Sommer thought about quitting law altogether.

But Hearn won on appeal in 2019. The Ontario Court of Appeal ordered McLeod’s estate to pay Hearn $60,000. He has yet to see a dime.

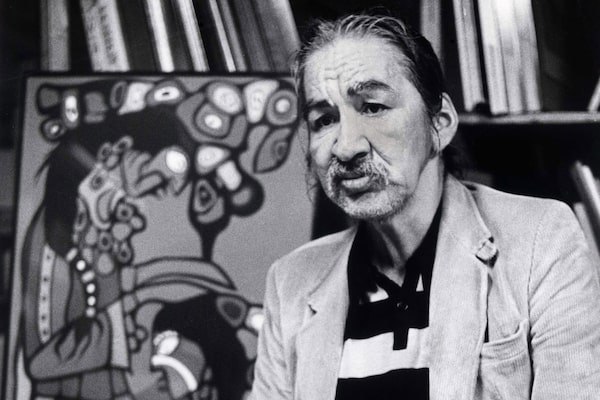

Indigenous artist Norval Morrisseau, in front of one of his earlier paintings, at a Vancouver gallery on May 11, 1987.Chuck Stoody/The Canadian Press

The fallout continues. Last year, Justice David Corbett ordered the Goldis to pay Sommer around $475,000 for their “campaign of internet defamation and harassment.” He also issued an injunction forcing them to remove the defamatory content from their blog and barring the couple from communicating any disparaging statements about Sommer.

They soon violated the injunction by keeping the posts online for at least two weeks after its issuance, and by sending a letter to McGill University officials urging them to cancel an appearance by Sommer at the school – two incidents cited in Sommer’s contempt of court motion.

But the Goldis managed to evade contempt hearings for months, ignoring all court documents left at their house, failing to answer multiple visits from the police and missing a court date late last year. Finally the court issued bench warrants for their arrest – the reason for their seven-day imprisonment.

Wearing shorts and a black sweatshirt bearing the slogan “Pay Your Dues,” John chose to represent the couple during the April 21 contempt hearing. He insisted that he took down the offending posts as soon as the injunction was issued. And he said he refused to open court documents or any other “anonymous garbage mail” at his house because it could contain poisons such as ricin or anthrax.

Had the Goldis opened their mail, they would have learned that the regional sheriff’s office seized title to their Mississauga home on April 1 and scheduled an auction for May 11 to pay off the balance owing to Sommer.

When Justice Corbett mentioned the auction in court, John stuck out his right thumb and forefinger in the shape of a gun and put the imaginary barrel to his head. Justice Corbett overheard Joan saying the couple should burn down the house and commit suicide. Alarmed, the judge demanded an explanation and pondered sending the Goldis for a psychological assessment.

“We were joking,” said Joan. “Our house is full of valuable art that we are going to donate.”

In his decision, Justice Corbett agreed the Goldis were in contempt, sentenced them to time already served in jail, ordered them to transfer ownership of two web domains to Sommer and awarded Sommer costs.

“It is hard to imagine how these proceedings could have gone more poorly for them,” said the judge in his decision.

“Your conduct is a disgrace,” he continued. “You need to grow up when it comes to these things.”

The Goldis were permitted to return home. But on May 8, police were called to their address once again. Police allege that John had uttered a threat to “cause bodily harm or death” to his wife.

With hours to go before the sheriff’s auction on their home, a neighbour of the Goldis contacted Sommer proposing a deal: If he agreed to pay the Goldis’ $550,000 legal bill, would Sommer cancel the auction? The neighbour apparently felt bad for the couple and wanted an end to all the police activity on the otherwise quiet suburban street.

“He told me he made some kind of deal with them and paid me the full amount owing, so I cancelled the sale with the sheriff’s office,” said Sommer. “I then phoned my mechanic to tell him I could finally fix the brakes on my truck.”

For Sommer, it’s not over. There are more clients who say they were defrauded, and the coming criminal trial against the eight alleged fraudsters. But he hopes the Goldis are done with him. “In court they said they loved to go bird watching and go to folk festivals,” he said. “I hope they focus on those positive endeavours and stop everything else.”