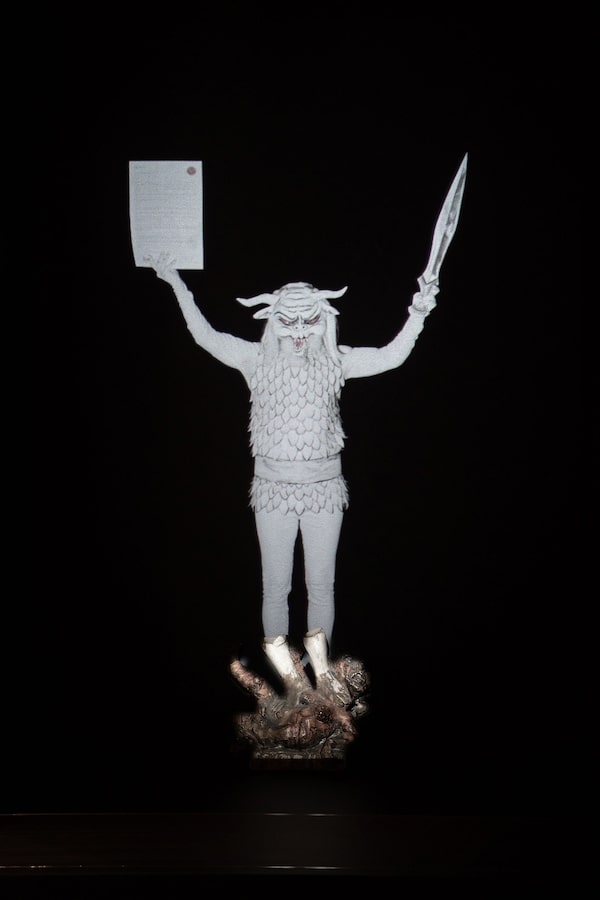

In The Trampled Devil, a video by Shary Boyle, the artist responds to an 18th-century wood carving that launched the Devil Museum collection but which is missing its top half, the figure of an avenging archangel suppressing evil.Martynas Plepys

The city of Kaunas in Lithuania is home to an unusual institution: The Devil Museum houses a collection of 3,000 sculptures, masks and folk carvings that represent the devil, whether that’s Satan or a mere trickster. And these days, the historic demons from around the world have some wicked company: contemporary works created by Canadian and Lithuanian artists.

Canadian art curator Josée Drouin-Brisebois has installed the works in the Devil Museum for the Kaunas Biennial. She points out, in an interview, that the devil is not necessarily evil incarnate; in many cultures, he’s a prankster or a shape-shifter, a destabilizing character of folk tale. Those figures seemed to fit this year’s exhibition, entitled Once Upon Another Time, which explores themes of storytelling, transformation and instability, and which uses the Devil Museum as one of several unusual venues in a city in the midst of its own reincarnation.

Kaunas, the second largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important textile centre in the days when it was part of the Soviet Union, is a place trying to move beyond its gritty industrial past by redeveloping or repurposing abandoned factories. Along with Esch-sur-Alzette in Luxembourg, it has been named the cultural capital of Europe for 2022.

“It’s a moment of transformation and it could go in so many different directions,” said Drouin-Brisebois, who is the contemporary art curator for the National Gallery of Canada. She was invited to curate the biennial show after a visit to the Lithuanian city in 2019.

Representing Canada at the Devil Museum are unsettling sculptures featuring crystals, hair and a werewolf figure by David Altmejd, a Montreal-born artist now based in Los Angeles, as well as an installation by Toronto artist Shary Boyle. An 18th-century wood fragment known as Trampled Devil, the carving that launched the museum’s collection, is missing its top half, the figure of an avenging archangel suppressing evil. Costuming herself as the angel, Boyle restores the absent figure in a silent video that uses manual animation techniques on an overhead projector, hand-made props and a folksy aesthetic to bring the angel and other archetypal figures to life.

Representing Canada at the Devil Museum are unsettling sculptures featuring crystals, hair and a werewolf figure by David Altmejd, a Montreal-born artist now based in Los Angeles.Martynas Plepys

The third artist in the venue is Lithuanian Lina Lapelyte, the composer and music director for the acclaimed Sun & Sea (Marina), an opera about climate change sung by sunbathers on an artificial beach, which won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 2019. In Kaunas, a video of what happens with a dead fish?, a water piece Lapelyte mounted in a specially made swimming pool for a show in Belgium last year, is projected at three different levels. It features amateur choristers singing on themes of expiration as they descend into the pool; screens show the swimming singers filmed from above and under the water.

This unusual encounter of European and Canadian art continues through three other venues and several outdoor public spaces as Drouin-Brisebois considers questions as topical as ecological instability and urban renewal, and as universal as transformation after death.

In the Museum of Zoology, a Soviet-era building that includes displays of stuffed animal specimens, she has included a 2017 video installation by Jeremy Shaw, a Canadian artist who lives in Berlin. Liminals, screening in a basement space, is a pseudo documentary set in a future where humanity is threatened with extinction and various characters seek a higher plane – a space between the physical and the virtual. Elsewhere in the museum, Lithuanian artist Emilija Skarnulyte created a piece about geological time that uses lasers to scan the animal displays three times a day.

The Canadian and other foreign artists worked through translators to communicate with organizers, so perhaps inevitably language resonates as a theme. The biennial’s film program includes several works by Inuit director Zacharias Kunuk and the video collective Isuma, including their 2019 Venice Biennale entry One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk. It features an encounter – through a translator – between a Canadian government officer and an Inuit hunter who refuses to abandon his nomadic life. That experience is literally thousands of kilometres away from Lithuania, but Drouin-Brisebois felt it was appropriate: Small villages kept the Lithuanian language alive during the period when the Soviets imposed Russian on the cities. (The Isuma films are scheduled to screen during the opening weekend of the European Capital of Culture event from Jan. 21 to 23.)

From The Trampled Devil, a 2021 video work written, directed and performed by Shary BoyleMartynas Plepys

Canadian artist Althea Thauberger also investigated cultural change and resistance in Lithuania, travelling to the nearby village of Sitkunai to interview women who worked at the radio station there, a facility buffeted by history since its beginnings in the 1930s. The artist created a performance piece and a video based on that research.

The largest venue for the biennial is the House of Basketball, a new building that will become a basketball hall of fame after the exhibition is over. (”I kept reminding them a Canadian invented basketball,” Drouin-Brisebois said of Lithuania’s national sport). There, various works speak to the city’s importance as a textile centre; the biennial itself began as a textile exhibition in 1997 before evolving into an art show.

To create a large woven tapestry entitled Seed Bank, Kapwani Kiwanga, a Canadian artist who lives in Paris, researched the remarkable story of African rice, an increasingly rare type that still exists in South America. It was smuggled there by enslaved Africans, who hid it hidden in their hair or clothing and then planted it in wetlands when they escaped. Meanwhile, Laura Lima, a Brazilian fibre artist and the one South American in the show, discovered that because of shortages she could not get hold of the dyes she wanted for her work. Instead she developed natural vegetable dyes and created large-scale textile “drawings” through video conferencing with two Lithuanian weavers.

That was typical of how the biennial came together: After her initial visit in 2019, Drouin-Brisebois only managed to visit Kaunas again to install the show. Many of the artists also had to do without the usual site visits. Still, 20 of the 31 participants did make it to the November opening.

“It felt amazing; there was so much collaboration,” Drouin-Brisebois said of the process of planning a major exhibition almost entirely through video conferencing. “Thinking about things across borders almost became easier. This could be a way of working in the future.”

The 13th Kaunas Biennial continues to Feb. 20.

Work by Brazilian fibre artist Laura Lima at the House of Basketball.Martynas Plepys