The McMichael Canadian Art Collection is hosting a comprehensive retrospective on artist Bertram Brooker, from Feb. 10 through to June 2.Supplied

In 2009 an ad ran in this newspaper, a “wanted” poster asking for help locating a Bertram Brooker painting for the exhibition The Nude in Modern Canadian Art at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. The curators were on the hunt for Brooker’s iconic and controversial painting from 1931, titled Figures in Landscape, which realistically depicts two naked women amongst a landscape of water and rolling hills. The ad went unanswered.

The painting was originally supposed to be included in an exhibition at the Ontario Society of Artists at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). At the last moment, the painting was pulled from the show; the content was deemed unacceptable. In response, Brooker wrote a rebuttal titled “Nudes & Prudes” that decried censorship in Canada and the arts. The location of Brooker’s Figures in Landscape was thereafter unknown – until now. It will be shown at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection’s comprehensive retrospective on the painter, titled “When We Awake!”, from Feb. 10, 2024 through to June 2, 2024.

“This was the Holy Grail. When I started working on the show, I thought there was no way we were going to find this painting,” said the curator of the exhibition, art historian Michael Parke-Taylor. “I know my colleagues have been looking for it. They hadn’t been successful. John [Geoghegan] was over at my place, and I gave him a small clue. I’d found the first initial and the last name of the person who bought it, supposedly living in Toronto, and that was on a Friday. On Sunday, I got an e-mail from John that says: I found it,” he continued. The collector had no clue he was in possession of a sought-after painting.

The painting will be included among 150 artworks by Brooker, a collection of work that shows his protean style. Brooker was someone who appeared to have an insatiable curiosity about life. He consumed all forms of art and culture: from music and literature to advertising and spirituality. The works in the exhibition include everything from illustrative panels based on the canon (such as Les Misérables and Crime & Punishment) to a geometric brass sculpture that resembles a seated figure when viewed from a certain angle. Parke-Taylor, who has been working on the exhibition for five and a half years, refers to his focus as “discovery art history.” “I love what I call discovery art history. And Bertram Brooker is an artist begging to be discovered in so many different ways. Most people would know him as having the first abstract exhibition in Canada in 1927,” said Parke-Taylor.

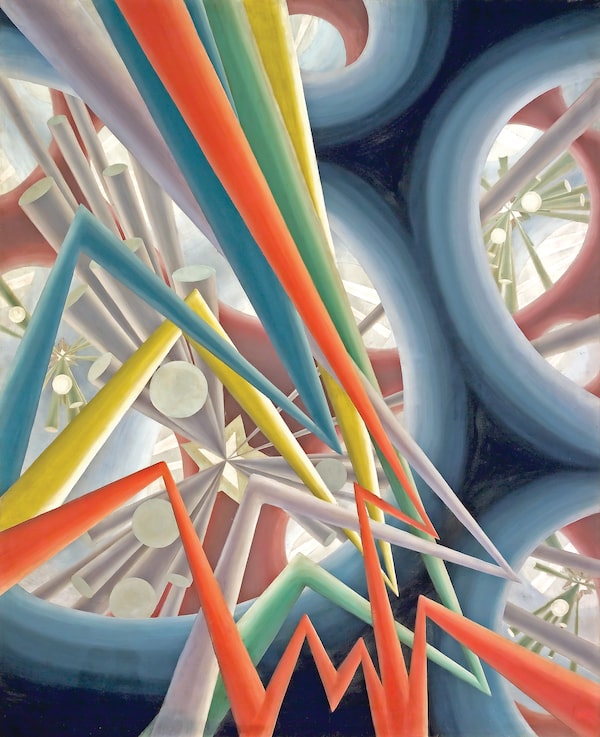

Central to the exhibition is 'Sounds Assembling,' from 1928.Supplied

Along with his painting practice, which spanned most of Brooker’s life, he was also an avid writer. Brooker authored a syndicated bi-weekly art column titled “Seven Arts,” which included architecture, painting, sculpture, dance, drama, poetry and music – an apt nod to Brooker’s broad interests.

The exhibition title “When We Awake!” is taken from the introduction text Brooker wrote for the Yearbook of the Arts in Canada 1928–1929, which is displayed in a vitrine at the McMichael. While Brooker was close to the Group of Seven, especially Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald, he was often suspicious of their nationalistic lens, instead seeing painting as a universal act that saw no borders. “[Brooker] wrote the introductory text of [the Yearbook] called When We Awake, which is the title of the show,” said Parke-Taylor. “It was a very positive text that he wrote, in which he was advocating for Canadians to really discover themselves and move into the future. He didn’t think the Group of Seven, for example, represented art for a nation. He was very leery of the Group’s nationalism; he really felt that art transcended borders,” continued Parke-Taylor.

Central to the exhibition is Brooker’s better-known piece, Sounds Assembling, from 1928. For art lovers, an obvious comparison of Brooker’s abstractions is Wassily Kandinsky, who was creating kinetic and heavily pigmented abstractions at the same time. They both shared a love of music, finding the two mediums interconnected. “[Brooker] found [Kandinsky] stultifying because it was too literal, in his mind, the connection between certain colours and music,” said Parke-Taylor on the common comparison. “I think [Brooker] was much more intuitive. He was passionate about music. He could listen to music and think of it in abstract terms.” The exhibition includes chances to listen to Handel, Mendelssohn and Bach – all composers that serve as inspiration for Brooker’s work.

Often referred to as a Renaissance man, Brooker has a voracious appetite, something that nicely comes across in the exhibition at the McMichael.Supplied

Perhaps the final room in the exhibition does the best job of capturing the scope of Brooker’s work. While he shifted from abstraction to realism in around 1930, he never completely disregarded abstractions. Alongside a realistic painting of cabbage and pepper is a geometric version of the same painting. “I think he was a bit of a show-off; he’s like, ‘I can do old master realism, and I can do avant-garde modernism at the same time,’ ” said Parke-Taylor.

Often referred to as a Renaissance man, Brooker has a voracious appetite – something that nicely comes across in the exhibition at the McMichael. Through discovering Brooker, there’s the chance to discover a lot more: his peers creating work at the same time, books to read and maybe new music to listen to. If you’re inclined, you can even take some Brooker home with you in the form of his novel, The Tangled Miracle, available for purchase at the gift shop.

Through discovering Brooker, there’s the chance to discover a lot more.Supplied

Editor’s note: The exhibtion opened at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection on February 10. Brooker's novel "The Tangled Miracle" is available for purcashe at the exhibit. An earlier version of this story contained incorrect information.