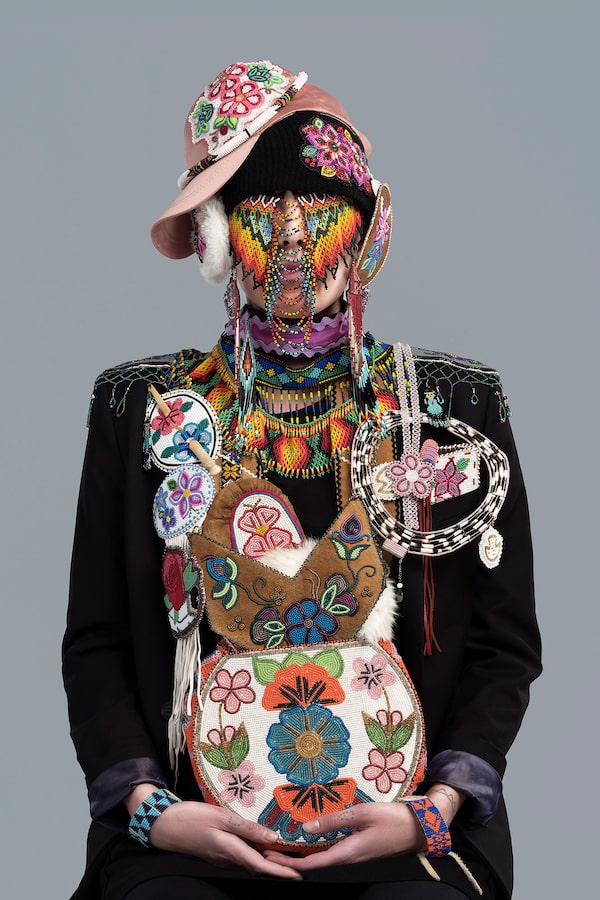

Aaniin, 2022. By Nico Williams, Anishinaabe and member of Aamjiwnaang First Nation Community. Glass beads, collection of the artist.SHAWN FULTON/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

When Cathy Mattes was 19 years old, her aunt – who thought Mattes had been spoiled growing up – set out to teach her generosity and patience through the gift of traditional Michif beading.

The two sat at the kitchen table and Mattes began her lessons. What was originally only supposed to be three days turned into two weeks of meticulously learning how to separate beads with a needle and sew with sinew in order to create a pair of moccasins. Each time she would make a mistake, or the work was not up to par, her aunt would rip up her work until she got it right.

But she was steadfastly encouraged, her aunt often saying, “You’ll get it right. You’re almost there.” Not only did she learn patience, and colour palettes, she learned generous reciprocity – which she passes on today.

Mattes is now one of three curators of Radical Stitch at the Mackenzie Art Gallery in Regina – one of the largest ever exhibitions of beadwork. It features 48 artists at different stages of their careers from across North America/Turtle Island and includes three commissioned pieces. The Mackenzie, which was one of the first public art galleries in Canada to hire Indigenous curators in full-time permanent positions, chose to showcase artists who engage with beads as a communication tool.

The exhibition is a contemporary look at how beadwork is redefining representation and cultural determination, says Michelle LaVallee, one of the other curators. She hopes beadworkers come and revel in the massive presentation of pieces that include wearable works, portraiture, installations and video.

Three artists included in the exhibition spoke with The Globe and Mail.

Judy Anderson

Nehiyaw, George Gordon First Nation, Sask.

One of Anderson’s pieces in the exhibition is titled Every time I think of you, I cry. She created it in honour of her brother who was part of the Sixties Scoop and, she says, taken from them when she was only two years old. The artwork is 9 feet by 7 feet and done with clear beads and fringe, both meant to signify the amount of tears she has cried over the years, mourning her brother.

Anderson identifies with the Indigenous saying, “beading is medicine.” To her, beaded items are much more than aesthetically pleasing: Beading is meditative, and often the designs can come to Indigenous people spiritually or through ceremony.

You can learn a lot about a person by their beadwork, she says, as it often tells a story about whoever is wearing it.

“Beads have a way of bringing us together in the community,” Anderson says. “If I’m at a pow wow, I can look across the room and see their colour is this, and so they do this, and they’re from here. You just learn that.”

Dana Claxton

Wood Mountain Lakota First Nation in Treaty 4 Territory

Jeneen, 2018. By Dana Claxton. LED firebox with transmounted chromogenic transparency.courtesy of the artist and Forge Project, NY

For Dana Claxton’s piece Jeneen, she had different collectors sit with her as she organized their beadwork on mannequin-like figures. Headdresses typically cascade behind a person, but this one falls in front, showing every beaded piece in detail. Claxton calls it an “inverted headdress.”

Indigenous people did not always have the privilege of wearing beadwork, Claxton notes. The Indian Act prohibited the wearing of traditional regalia, along with indigenous spirituality and dances, until 1951. It forced them to go underground and affected the creation of beadwork and regalia.

This is why Claxton sometimes feels as if she is “on display for non-Indigenous people,” when wearing beadwork. She recalls wearing a beaded necklace to work one day, and her non-Indigenous co-worker reaching into her blouse to try to grab it for a better look. She felt violated.

“It was really offensive to me,” says Claxton, adding that the incident spoke to the privilege to which her co-worker felt entitled.

“Beauty doesn’t just belong to Greek Western philosophy. We have a profound aesthetic beauty in our communities that is like no other. It’s so distinct and unique to our tribal communities. That’s powerful stuff.”

Ms. Claxton hopes people bask in the beauty and sheer size of the exhibit – and that Indigenous people are inspired to bead not only traditional regalia, but baseball caps, jean jackets, toques, purses, jewellery and anything else they can get their hands on.

Nico Williams

Anishinaabe and member of Aamjiwnaang First Nation

Amazon Bag, 2022. By Nico Williams, Anishinaabe and member of Aamjiwnaang First Nation Community. Glass beads, collection of the artist.SHAWN FULTON/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Williams often beads things he finds on the street.

“I’m always trying to channel objects that speak to indigenous communities that sort of represents us or can have a conversation with the colonial stuff that’s going on here in Turtle Island,” he says.

When he started, he was relegated to small boutiques. Now, Williams has a beaded Amazon bag included in the exhibition.

“I’m always thinking about our ancestors or even beaders on the pow wow trail,” Williams says. His grandmother was always beading, yet his family does not have a single item of hers left. This is common in Indigenous families, he says: Beaders create something and as soon as they are done, it is sold and out the door.

About the exhibition, Williams says: “Opportunities like this haven’t really happened until recently, as there’s been an explosion of beadwork on social media like Instagram.”

Sign up for The Globe’s arts and lifestyle newsletters for more news, columns and advice in your inbox.